Restoring Confidence, 1 Grain at a Time

The rice growers of Fukushima have been working hard to restore the nation's trust in their best grains. Let's take a look at the state of the crops in the wake of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami.

By Du HaiLing

When I got off the train at Fukushima Station on September 22, my heart stopped when I saw the two Chinese characters for “Fukushima.” My heart ached, I should say. Since the earthquake and tsunami of March 11, 2011, the two characters for Fukushima have taken on a sorrowful ring. This despite the fact that it’s only an hour and 22 minutes from Tokyo on the shinkansen.

My first stop was the Crop Production Division in the Fukushima prefectural government offices. Speaking to Yoshihito Tanji, desk chief for the Crop Production Division, I was handed a set of papers and given a detailed explanation on why the prefectural government was screening every single bag of rice produced in Fukushima. In October 2011, Fukushima Prefecture carried out a monitoring survey based on central government standards and approved the shipment of rice for sale. On November 16, however, rice exceeding the standard radiation value was detected in unpolished rice from the former Oguni-mura in Fukushima City, and press at the time went into an uproar. Fukushima Prefecture carried out an emergency inspection, but the word “radiation” was already etched into people’s minds. In 2012, Fukushima Prefecture decided to start screening every single bag of rice. This meant that all the rice produced in paddies throughout Fukushima Prefecture, down to the last grain, would be screened for radioactive cesium. In order to produce the machinery that could handle the screening, bids were gathered from several domestic manufacturers. Tanji said that, within four months, a new screening machine exclusively for rice was developed. The machines are extremely expensive, at approximately ¥20 million (US$176,491) each. They are also extremely efficient, able to screen two or more 30-kilogram (66-lb) bags of rice for radioactive material in one minute.

As a rice screening organization, the Fukushima Association for Securing Safety of Agricultural Products has been established at the prefectural level. The association is comprised of Fukushima-ken Nogyo Shinko Kosha (the Fukushima Prefecture agricultural promotion corporation), JA Fukushima Chuo-kai (JA central Fukushima), JA Zen-Noh Fukushima (JA all-Fukushima agricultural co-op), as well as farm produce gatherers in the prefecture, consumer groups and other organizations. Their work includes centrally managing the rice screening data and publishing the results online, as well as seeking compensation from Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) to cover the screening expenses.

There are also local councils at the regional level. Fukushima Prefecture has a total of 38 such councils, comprised of municipalities, agricultural organizations, and produce gathering groups. These councils are responsible for arranging where the screening machines will be set, printing the labels to be affixed to rice bags, carrying out the screenings and entering the results into a data management system.

So who pays all these rice screening expenses? Including the costs for the organizations in the prefecture’s councils, where does the money come from? These are extremely practical issues. Although compensation is being sought from TEPCO, the utility company cannot possibly cover all the costs. In reality, the expenses are generally footed by the central government; that is, taxpayer money.

The rice screenings in Fukushima City are done inside a company warehouse, where the task of hauling in the bags has been made easy. At the screening location we visited, there were three of the expensive belt conveyor-type screening machines, with rice bags stacked up nearby. Each bag was 30kg. Before it was equipped with a suction-type hand crane, the rice was loaded onto the machines by hand. Workers carried bags from morning through night, their backs groaning in pain. Despite that, every single bag had to be screened. This was back in 2012, when the tests had just started. Although most farmers were elderly, they had to haul in 30-kilogram (66-lb) bags of rice for screening. This was a huge burden on farmers. Each and every farm was visited in order to explain the situation but, despite being a seemingly simple task, hauling rice bags to the screening site proved to be a major undertaking. In order for the screenings to be done properly, the prefectural government held a training course, and currently employs approximately 1,500 inspectors.

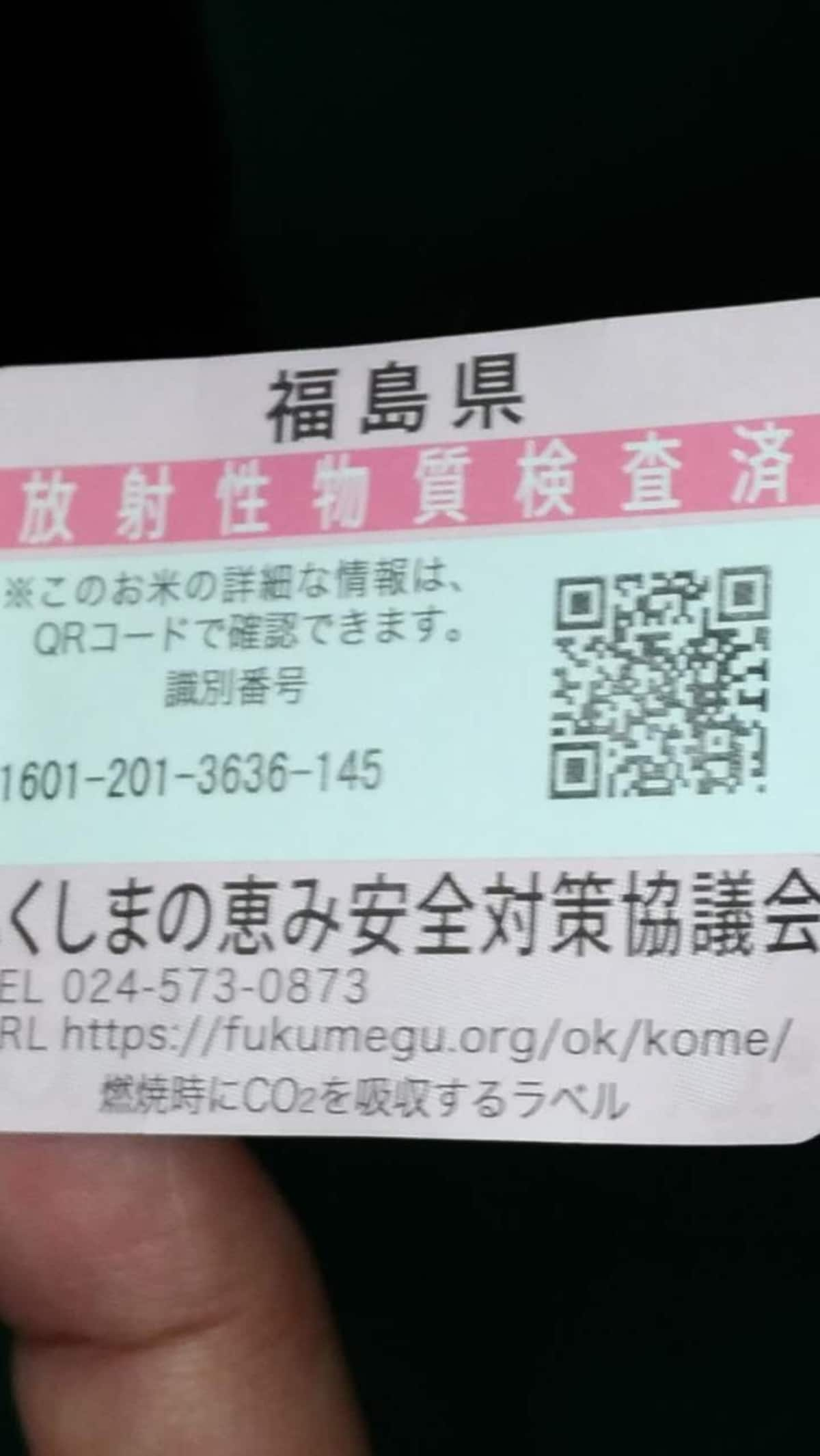

The workers at the screening site showed me a general demonstration of the screening process. Rice is loaded onto a cart and brought close to the screening machine, from which a suction pad-fitted hand crane lifts it onto the screening machine. By simply sticking the suction pad to each bag, any employee can easily lift rice onto the screening machine. Barcode labels for the screenings are also affixed to the rice bags, with numbers showing where the rice was grown, the names of the farmers, and what number bag they are. Labels are printed according to the size of the rice paddies owned by the farmer, and any leftover labels are collected. During screenings, the barcode labels are scanned and screenings conducted, as rice bags that passed are affixed with a label showing so. The labels are printed with the characters, “passed radioactive material screening,” along with a matrix barcode.

I was shown a demonstration of how the matrix barcodes are scanned from these labels in order to know where the rice was grown and its radioactive material screening results. The radioactive material screening results for all the rice is uniformly managed by a data management company using cloud storage technology.

For the screening results up until now, it is worth considering whether or not it is truly necessary to continue the screenings as-is. Since 2015, there have not been any cases of rice exceeding the standard radiation values. In other words, the rice has fully met the safety standards, and given nothing but “all clear” results in inspections over the past two years. Meanwhile, the costs for these inspections exceed ¥5 billion (US$44.1 million) each year. Are the screenings still necessary? Everyone has a different opinion.

I had the chance to interview a farming couple living in Fukushima City. The husband’s name is Koji Kato, and the wife is Emi Kato. They are young for farmers and have four children, aged preschool to middle school. I assumed they would think that the screenings were unnecessary; a waste of time and money. Instead, Koji Kato told me, “They should continue. Better yet, they should keep going for 50 more years, leaving a record every year that the rice is safe. If we don’t do that, no one will understand the determination of Fukushima Prefecture.”

Raising their four children and dog, the Katos live in Fukushima, mostly producing the Fukushima rice brand Ten no Tsubu (“Heaven’s Grains”). Compared to other, softer Japanese rice varieties, Ten no Tsubu has a slightly firmer texture.

In aging Japan, and particularly in Fukushima, whose population has seen a steep decline since 3/11, you rarely see a young farming couple like the Katos. For that reason, Koji gets a call whenever the news is covering farmers in Fukushima. The couple runs Kato Farm. Both Koji and Emi used to be ordinary company workers, but seven or eight years ago Koji inherited rice paddies and farming equipment from his grandfather. “This is a good way of life,” he said. “You’re in touch with the sky, earth and paddies, and are free to choose what time to start and end work. There’s no stress in interpersonal relations like you find at Japanese companies.” Emi, on the advice of her husband, was licensed as a rice paddy environment appraiser and rice advisor. Slim and short in stature, she said frankly, “No matter how much I help out with farm work it doesn’t amount to much, so I figured I should make use of special skills.” Besides raising their children and taking care of housework, Emi also promotes Kato Farm and Fukushima rice through Facebook and other social media outlets.

Kato Farm’s rice paddies are now twice as vast as they were before 3/11. This is because the farmers in their area had grown old, and much of their land was left in limbo after the disaster. The Katos focused their attention on these tracts and, to prevent Fukushima’s farmland from gradually falling into ruin, decided to rent them. Their paddies expanded little by little, and although rice plants began to sprout, the Katos’ income is far from ideal. Fukushima rice must regain the trust of consumers and regain its former status. It may be a long road ahead.

A variety of data on rice is published on Fukushima Prefecture’s website, and the 203 screening machines in the prefecture are running full-stop every day in order to measure the radioactive material data for all rice after it has been harvested. The data shows that Fukushima’s rice is safe. Actually, a great number of restaurants in the Tokyo metropolitan area are using rice from Fukushima. This means that we are regularly eating delicious Fukushima rice. Regardless of that, when consumers buy rice on the market, most of them still steer clear of anything from Fukushima.

According to a public opinion poll, 20 percent of respondents said they would never buy rice grown in Fukushima. The other 80 percent said they would buy it, or are waiting to see how things go. “If 20 percent of people won’t buy it, how can we boldly introduce Fukushima rice to the remaining 80 percent?” asked the Katos. “In order to show everyone the quality of Fukushima rice, we must continue screening every bag.” Of course, the ¥5 billion it costs every year to fund the screenings comes out of taxpayers’ pockets.

As I left Fukushima, I saw an orchard along the way. Apples, pears, peaches and other fruit hung heavy on the branches. Fukushima is originally famous as a fruit-producing area. Both Mr. Tanji and the Katos, who I interviewed for this article, said that they have never bought fruit since they were children. There are always relatives or friends growing fruit, so from the perspective of a Fukushima resident, buying and eating fruit seems unthinkable. This is a naturally abundant and beautiful land.