8 Ways Japanese Christmas is Weird

Christmas is celebrated in different ways all around the world. But Japan is a little odd in that it’s a largely non-Christian nation that invests a whole lot of energy in this most Christian of holidays—which has meant that a whole number of things have been lost in translation along the way.

By Michael Kanert8. Santa Comes Through the Window

https://pixabay.com/en/christmas-wishes-happy-holiday-2909253/

Aside from some homes in Hokkaido, Japanese houses have no chimneys, so Santa naturally comes in through the window. While this isn’t all that uncommon a belief in warmer climes, it’s had an interesting ramification unique to Japan: since there are no fireplaces to hang them by, Japanese people have no idea what Christmas stockings are for. While you might see them as decorations, seasonal sweets packages or ad-hoc wrapping paper—and you can find plenty in the ¥100 shop—kids in Japan won’t be hanging any stockings up to find them mysteriously filled on Christmas Morning. They’re just sort of there, part of the background without any clear purpose.

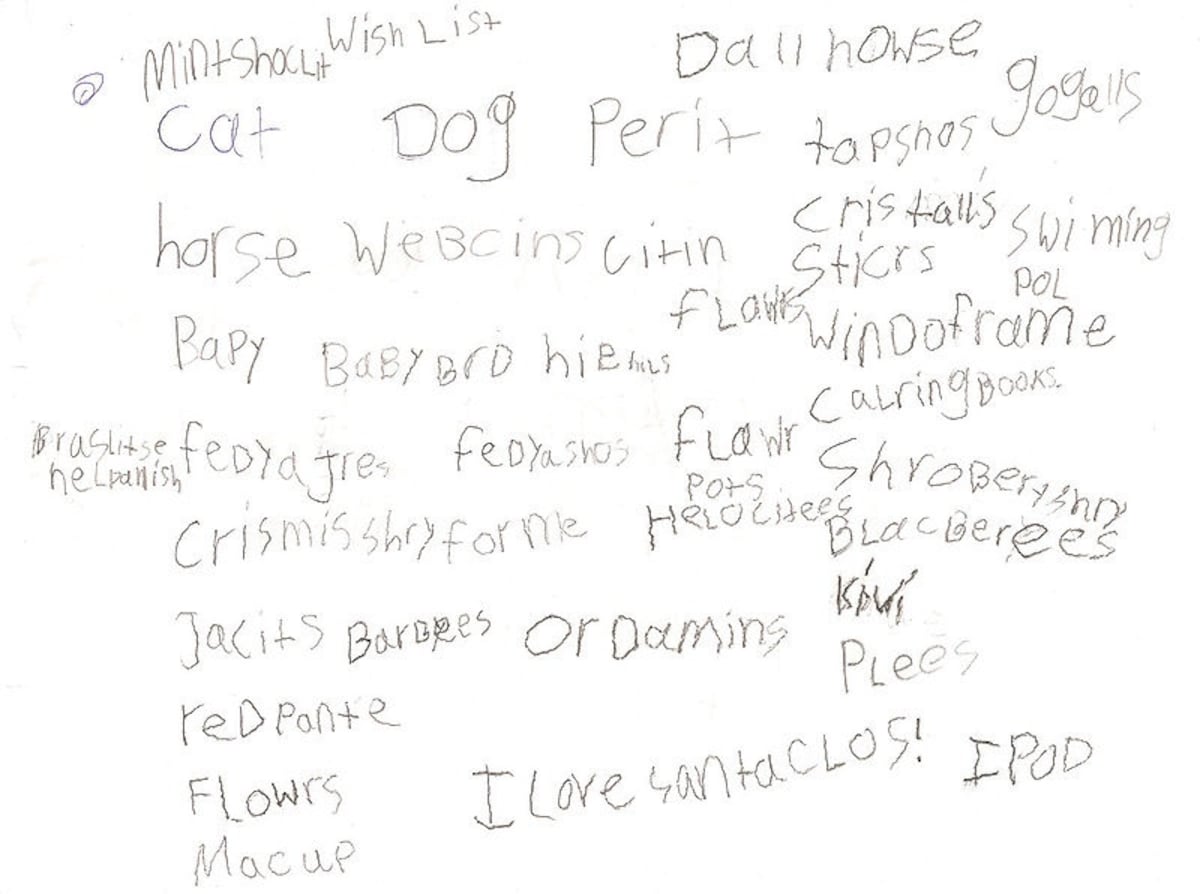

7. Christmas Lists Are One Item Long

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Christmas_wish_list_to_Santa.jpg

Japanese kids don’t ask for a huge list of things for Christmas: they ask for just one. But since Santa doesn’t come to Japanese shopping malls, the only way to notify him is to leave a letter by your pillow at night, or by the window for him to pick up as he passes by. And just like anywhere, some kids will write a polite, elegant letter asking Santa how he’s been all year, and others will scribble down “I want the new Call of Duty” and be done with it.

6. The Tree is Lonelier than Charlie Brown’s

Just as the meaning of stockings didn’t quite make it to Japan, neither did the purpose of the Christmas tree. While some Western chains like Costco and Ikea have recently begun to introduce live trees, it’s almost guaranteed that you’ll be using a plastic fir in Japan—though these tend to be very nice and remarkably inexpensive, available at most department stores and Toys “R” Us.

But that doesn't mean the trees get all that much respect: they're pretty much for show. Some Japanese people will put up a seasonal tree at home for the sake of sprucing up their interior design; others do it for their kids, and may just as well drop the effort when the little ones grow out of the excitement. Regardless, nobody will be putting a present under the tree: Japanese parents put their kids’ (singular!) Christmas presents beside their pillows overnight as they sleep. The tree isn’t involved at all.

5. The Colonel Owns Christmas Dinner

KFC has been building its hold on the nation since its first branch opened in Nagoya in 1970. But it was in 1974, with the Kurisumasu ni wa Kentakkii! ("Kentucky for Christmas!") campaign, that the nation truly went mad for fried chicken during the holidays.

As the story goes, the marketing brainwave was inspired by the observation of a group of foreigners who opted for KFC when they couldn’t find a turkey for Christmas dinner in the early '70s. The message stuck, and now even people who don’t get a tree or celebrate the season in any other way will still reserve a KFC set for dinner several months in advance.

KFC consistently records its highest annual sales volume during this time, with even executives coming out to help deal with the long lines. Colonel Sanders gets dressed up for the season, too—and since many Japanese KFC branches have life-sized effigies of the Colonel out front, he’s pretty hard to ignore! Walk by a KFC on December 24, and don’t be surprised if the entire shop is filled floor to ceiling with meal boxes waiting for delivery!

And like most aspects of Japanese Christmas, this sumptuous feast is enjoyed not on the 25th, but on the 24th.

4. People Actually Want Christmas Cakes

Along with KFC, having a Christmas cake is a big part of Japanese Christmas—and if you’re not having the one, you’re probably having the other.

Japanese Christmas cakes aren’t like the famously dreaded fruitcakes you’ll find hot-potatoed around North America, or the delectable (if dry) Weihnachtsstollen (Christmas Stollen) you might find in Germany. Rather, they’re usually a strawberry shortcake with a seasonal message on top—though you can easily find some more elaborate cakes if you’re willing to open your wallet!

Most people reserve their Christmas cake well in advance, and while there’s a good chance they’ll sell out if you don’t put your name on the list, you can still often get lucky if you head to the department store attached to any major train station as late as the afternoon of December 24. Just don’t be too picky!

3. Christmas Isn’t Family-Friendly

https://www.photo-ac.com/main/search?q=%E3%82%AF%E3%83%AA%E3%82%B9%E3%83%9E%E3%82%B9%E3%80%80%E3%83%87%E3%83%BC%E3%83%88&qt=&qid=&creator=&ngcreator=&nq=&srt=dlrank&orientation=all&sizesec=all&mdlrlrsec=all&sl=en

As a traditionally Shinto and Buddhist nation, Japan doesn’t have any major cultural or religious foundation for celebrating Christmas. In fact, it’s not uncommon for kids to think the whole extravaganza is simply for Santa’s birthday. Just like Valentine’s Day and its locally invented sibling, White Day, Japanese Christmas is purely a commercial endeavor.

The holiday was originally adopted in an effort to gain acceptance among Western nations—just as tattoos were banned in the Meiji Period (1868–1912) for the exact same reason. While Christmas really kicked off in the '60s, it’s purely marked by consumerism, and workers can expect to be in the office as usual on December 25—though the emperor’s birthday on the December 23 offers a reasonably close respite.

In fact, December 25 is pretty much an afterthought: the big deal is on the 24th. And the comparison to Valentine’s Day is more apt than you’d think: with all the money flying around and the ubiquitous seasonal illumination throwing romance into the nocturnal air, Christmas Eve has become another occasion to show your special someone just how much you care.

So rather than spend the evening with their families, Japanese people do all they can to get time alone with their significant other—with hotels, restaurants and jewelry stores only too happy to offer Christmas specials to sweeten the deal. Seasonal magazines and TV shows present advice on where to have a successfully romantic Christmas date, what to buy for a present and just how much is the right amount to spend—making it a very depressing time if you’re on your own. It gets to the point where people will do everything they can to get a boyfriend or girlfriend by the 24th... which leads to the next item on our list.

2. People Celebrate Their Loneliness on Live TV

Sanma Akashiya, better known as Sanma-san, is one of the three biggest entertainers and talk show hosts in Japan. Every year on Christmas Eve, he and actress Akiko Yagi host Akashiya Santa Shijo Saidai no Christmas Present Show, or Akashiya Santa’s Biggest Christmas Present Show Ever. It’s intended for people who are lonely on Christmas Eve.

Prior to the show, people can write in and share their stories of loneliness from throughout the year. Sanma-san then picks the most interesting respondents and gives them a call. If you’re able to entertain him on the phone, you get a chance to call out a number from a huge bingo board and win a random prize, which might range from a One Piece toy to a bag of rice, golf clubs, a refrigerator, vacation tickets or even a car!

1. Decorations Are Dead by December 26

While you won’t necessarily see individual houses celebrating the season, every retail shop in Japan will be plastered with Christmas paraphernalia within days of Halloween. Yet they all come down just as suddenly, and you’ll see the process begin around the country from about 10 p.m. on December 25.

Why? Because while Christmas is a commercial holiday, New Year’s is the biggest event on the Japanese cultural calendar. Most companies will take at least three days off around the end of the year, and much of the country is quiet from December 31 to January 4.

In effect, New Year’s is the Japanese Christmas. Unlike December 24, New Year’s is the time when families get together, clean their homes, have special meals, pray at the shrine or temple and prepare for the coming year. You’ll eat osechi ryori, maybe go ring the local temple bell at midnight (traditionally rung 108 times to wash away the 108 human sins of Buddhist belief), and if you’re a kid you’ll get your otoshidama—an envelope filled with money—on New Year’s Day.

By December 26, all the Santas and wreaths in the country will be replaced with kadomatsu—literally “gate pines,” which consist of pine branches combined with cut pieces of bamboo—and shimenawa, or “enclosing ropes,” which are rice straw ropes hung on doors and even on the fronts of cars around New Year’s, and which you’ll also see around sacred trees and gates at Shinto shrines every day of the year.

So is Japanese Christmas out-and-out crazy? No. But it's just odd enough to raise a few eyebrows until you figure out what it’s all about.