Touring the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant

Of all the places you can travel in Japan, from ancient temples to pulsing cities to bracing mountaintops, one of the least known is the stricken Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant. Timothy Hornyak takes a scheduled tour of the plant, at one time considered one of the most dangerously radioactive places in the world.

IAEA Director General Rafael Mariano Grossi visits Fukushima Dai-ichi in 2022 (Photo courtesy Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings, Inc.)

The Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant was severely damaged in the March 11, 2011 magnitude-9 earthquake and tsunami that devastated northern Japan. When the flooded generators for the cooling system failed, the meltdowns, hydrogen explosions and massive radiation release resulted in mandatory evacuations of thousands of people.

Twelve years after the disaster, however, decontamination efforts have made headway. Not only have most evacuation orders been lifted, visitors can tour the Fukushima plant safely, with minimal radiation exposure.

Dai-ichi today

A sign by the roadside welcomes people to the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant (photo credit: Tim Hornyak).

Why go to Fukushima Dai-ichi? You might have an interest in “dark tourism,” the allure of a forbidden site, or the enormous engineering challenges of managing and taking apart a wrecked nuclear power plant. Or you might want to simply learn more about the catastrophe and its aftermath. Whatever the reason, it’s important to know about the current situation at the plant before you go. Today, it’s a hive of activity—at times, there are over 4,000 workers at the plant, but biohazard suits are no longer required in over 90 percent of the complex. That means it’s relatively easy for visitors to enter and learn about operations there.

"Stored in about 1,000 house-sized tanks all over the complex, the volume reached about 500 Olympic swimming pools."

Fukushima Dai-ichi grabbed headlines in 2023 when operator Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s (TEPCO) announced it would begin dumping some of the 1.3 million cubic meters of water that has been used to keep the nuclear fuel and other debris cool. Stored in about 1,000 house-sized tanks all over the complex, the volume reached about 500 Olympic swimming pools and continued to grow by roughly 100 tons a day. TEPCO’s rationale for the move was it was running out of room at the large plant and needed space to setup facilities for decommissioning work, a job that’s expected to last at least until the 2050s.

With the backing of the Japanese government and the U.N.’s International Atomic Energy Agency, TEPCO began flushing the wastewater into the Pacific Ocean after treating it with a purification system designed to filter out radioactive contaminants. The wastewater release was controversial, prompting opposition from marine scientists and a ban on Japanese seafood in China, but early seawater tests have not shown elevated levels of radiation.

Is it safe?

A TEPCO staff member instructs visitors on safety tips and how to wear protective gear (photo courtesy Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings, Inc.).

Is it dangerous to visit Fukushima Dai-ichi? It really depends where you go and how much time you spend there, but it seems to be a safe experience for the average visitor. You will probably be exposed to a small amount of radiation. Tours may be a combination of bus rides and brief walks inside the complex. Depending on your tour, you may be given a personal dosimeter to measure the radiation you’re exposed to, as well as protective gear such as helmets, gloves, boots and N95 filtration masks.

Dosimeters with large displays are also found throughout the complex and in the minibuses that shuttle visitors around. The daily radiation limit for visitors is 0.1 millisievert, which is about the equivalent of a chest X-ray, but most visitors are likely to get much less exposure than that on a roundtrip flight from Tokyo to New York. Depending on the tour, some visitors may go through individual radiation checks that measures exposure before and after going to the areas around the reactor buildings.

Access to the complex and the facilities inside it is tightly controlled, so you can’t walk around freely. You’ll have to present photo ID, and go through security screening. You must follow your guide and obey all the rules. This includes restrictions on photography (in part due to the danger of terrorists using imagery to enable attacks on the complex) and just about any object you might want to bring into the plant.

What’s it like going there?

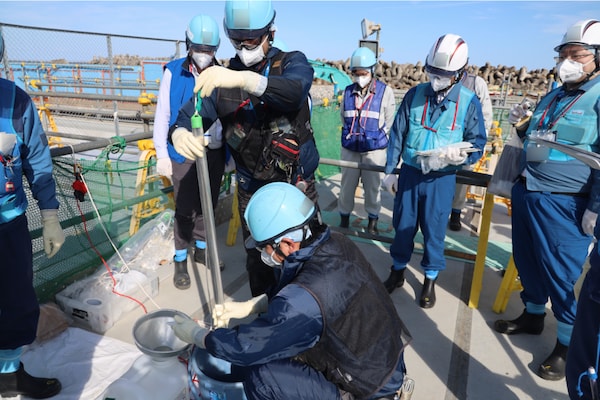

Plant workers and observers test wastewater after purification and dilution (photo courtesy Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings, Inc.).

Visits to Fukushima Dai-ichi usually begin at the JR Joban Line Tomioka Station or the nearby TEPCO Decommissioning Archive Center, a facility with exhibits and audiovisual materials about the disaster. From there, it’s a 20- to 25-minute bus ride to the plant itself, past abandoned stores, homes and car dealerships, many of which are now surrounded by weeds. Even in Tomioka itself, where there are recently built homes and shops, there are relatively few people and vehicles on the roads.

Once through the entrance, you may get a briefing at the plant headquarters on the edge of the complex. If you’re going to do some walking around inside, you may go through the security and health checks described above, before being outfitted with a dosimeter and protective gear. If you’re riding a TEPCO minibus down to the reactor building area or water-treatment facilities, there might be an onboard dosimeter. Watch as the numbers climb the closer you get to the reactor buildings by the coast.

Giant pipes in the Advanced Liquid Processing System for treating wastewater at Fukushima Dai-ichi (Photo credit: Kimimasa Mayama/EPA/POOL).

With an area covering about 3.5 million square meters, the complex is a town-sized maze of enormous construction equipment, storage tanks and large buildings where the wastewater is processed. There’s an eerie silence here, occasionally punctuated by the rattle of heavy machinery. There are few birds—most trees were removed after the disaster to make room for the tanks; the proportion of green space in the complex fell from about 60 percent to less than 25 percent.

Past the seemingly endless rows of storage tanks, down by the sea, are filtration and dilution units, emergency valves, holding tanks and networks of pipes used for the release of wastewater. In the shallow water nearby stands an immense metal containment tank has been mangled like a dog’s chew toy. Belowground is an undersea tunnel through which the treated water is discharged to a release point about 1 km offshore.

"The Blue Deck will likely be the most contaminated spot on the tour, as shown by a dosimeter display on the deck."

The highlight of a tour to Fukushima Dai-ichi is the Blue Deck overlooking Units 1 to 4, where explosions ripped through the buildings in 2011. The structures are in various states of damage or repair, but some contain highly radioactive nuclear fuel and debris that will have to be disposed of in the long decommissioning process. The Blue Deck will likely be the most contaminated spot on the tour, as shown by a dosimeter display on the deck, and while it offers a panoramic view of the heart of Dai-ichi, you may not want to linger.

Signing up for a tour

A dosimeter reads 61.3 microsieverts per hour as journalists survey reactor buildings where explosions occurred in 2011 (photo credit: Kimimasa Mayama/EPA/POOL).

Japanese-language tours are available. Hankyu Travel offers a three-day visit to the area for ¥79,900 per person). Finally, free tours organized by TEPCO itself are offered to journalists, diplomats and others through the auspices of organizations such as the Foreign Press Center Japan. However you get there, visiting the site of one of the worst nuclear disasters in history is an experience you won’t soon forget.

Presently, there are a few monthly English-language tours being held on a trial basis that go inside the complex as well as to the surrounding region and reopened evacuation areas where participants can meet with people rebuilding the community. A google search will find them if they are still being operated.