Obake in Japanese Popular Culture

The Obon Festival takes place in the middle of August and honors the deceased spirits of one’s ancestors. Naturally, this is the season when Japanese people enjoy talking about obake (ghosts/spirits/monsters/goblins) and engaging in obake-related activities.

By CHOPSTiCKS NYThe Origins of Obake Culture

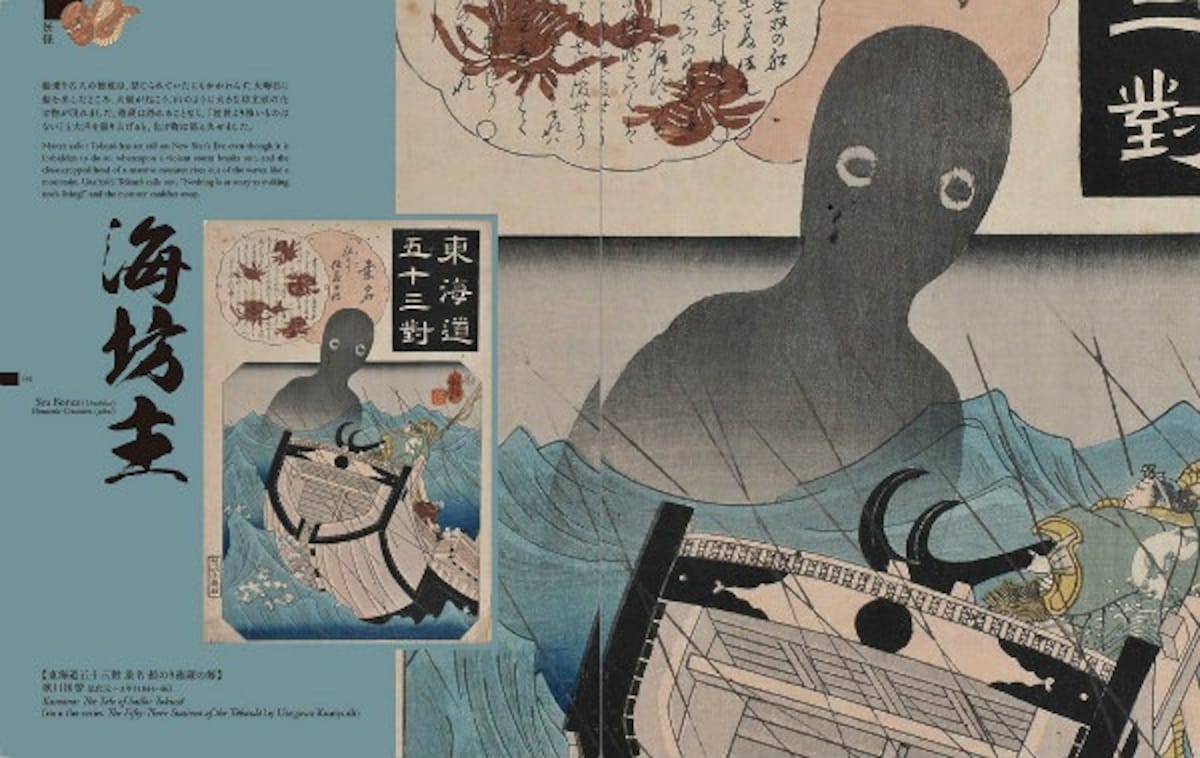

There are countless obake stories in Japan. Etymologically, obake comes from the word bakeru (to transform), and it refers to something that is different to a great degree from how it should look. Ghosts, monsters, fairies, goblins and ogres are all considered obake in Japanese culture. Since nature worship and animism are deeply embedded in the culture, Japanese people often think that natural transformation is some kind of sign, such as a rainbow after the rain, foliage in the woods, metamorphosis of insects and amphibians, etc.

Belief in Buddhism also contributed to the development of obake culture. The Obon customs in Japan based on Buddhism are a good example. During the Obon period over a few days in mid-August, usually from the 13th to 16th, it's believed that the spirits of the deceased visit the earth and stay with the living. In order to welcome and bid farewell to the spirits, people burn bonfires that work as guiding lights for the spirits. Customarily people go to their family graveyards and offer food during Obon as well. This tradition is one of the reasons why obake-related events take place during this period more than any other season.

Obake & Pop Culture

https://azukichi.net/season/summer/summer0407.html

One of the most common obake-related activities during the summer is kimodameshi. Directly translated as a “test of your gut,” this is a type of outdoor game that challenges participants’ degree of endurance toward fear. Usually held in graveyards, scary spots like haunted mansions, or simply dark places, a group or pair of people walk a certain route and come back to the starting point. It’s a common summer camp activity.

http://blog.goo.ne.jp/pegasus_es2004/e/6a93ca14f50fe85ac367932847b57968

Obake yashiki (haunted houses) are another common attraction. These are often found at festivals or in theme parks, and participants enjoy thrills and chills while walking through the spookily decorated house. There are a variety of tricks and gimmicks hidden inside that scare participants. A walk-through type of obake yashiki is the most traditional, but now you can also find variants that consist of rides, theaters and closed rooms with 3-D images and surround sound.

http://www.woodblockprints.org/index.php/Detail/Object/Show/object_id/1251

Rakugo, Japanese traditional comic storytelling, also has standard pieces maximizing the essence of obake. Obake themes are seasonal in rakugo, and they're usually performed in summer. There are various types of stories, from truly scary ones to ones with comic relief. The most popular pieces are the latter type, which include "Obake Nagaya" ("Haunted Tenement"), "Okyo no Yurei" ("A Ghost in Okyo’s Painting"), "Sarayashiki" a.k.a. "Okiku no Sara" ("Haunted Plate Mansion," a.k.a. "Plates of Okiku") and "Hettsui Yurei" ("Haunted Oven"). There are no visual aids during the performance, so it's solely the performers’ skills of delivering lines that makes audiences feel chilled or amused.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XG5mvupo9Wc

You can see numerous obake stories in movies, manga and anime. Kenji Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu Monogatari (1953) and Masaki Kobayashi’s Kwaidan (1964) are the most internationally known classic films based on ghost stories. Even Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood (1957), based on William Shakespeare’s Macbeth, includes an important segment involving ghosts. Most people still remember the chills from the modern J-horror series Ringu (1998), Ju-on (2002) and One Missed Call (2003).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9boVDep-diw

Manga and anime are full of obake characters, but the most influential is GeGeGe no Kitaro by Shigeru Mizuki. Originally created in 1960, it’s a story about a society in the world of yokai (hobgoblins in Japanese folklore). The protagonist is a yokai boy called Kitaro, who was born in a cemetery. GeGeGe no Kitaro has been adapted for TV anime series, live action films and video games.

Obake in Kabuki & Noh

http://youkoso.city.matsumoto.nagano.jp/ookabuki/blog/%E3%82%B3%E3%82%AF%E3%83%BC%E3%83%B3%E6%AD%8C%E8%88%9E%E4%BC%8E%E3%80%8E%E5%9B%9B%E8%B0%B7%E6%80%AA%E8%AB%87%E3%80%8F%E8%A8%98%E8%80%85%E4%BC%9A%E8%A6%8B%EF%BC%86%E5%85%AC%E9%96%8B%E8%88%9E%E5%8F%B0/

Obake stories are popular subject matter for movies, novels and even manga and anime, but they're also important in traditional kabuki and Noh theater performances.

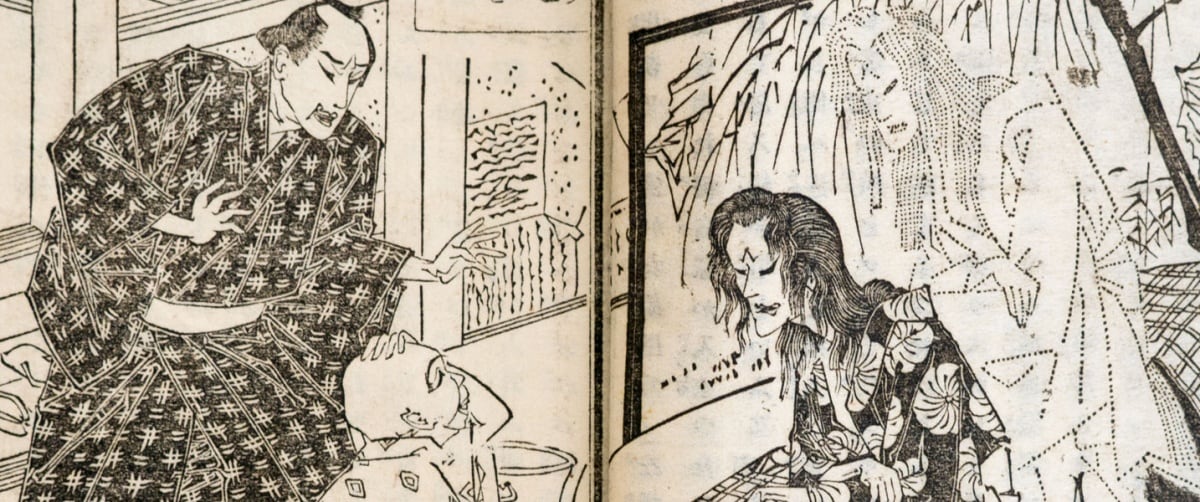

Packed with action, kabuki plays maximize visual effects, including hayagawari, or an instant transformation right in front of the audience. Obake are the perfect subject matter for jaw-dropping transformations. Yotsuya Kaidan, written in 1825 as a kabuki play, is popular not only in kabuki theater but has also become one of the most famous Japanese ghost stories of all time. It went on to be adapted for film more than 30 times.

With smooth, fluid movements and meditative music, Noh plays are quite opposite in style to kabuki, but they're inseparable from obake. Within Noh plays, there's a subgenre called mugen Noh that deals with spirits, ghosts, phantasms and supernatural worlds. Usually characters from the two worlds of the living and the dead switch seamlessly in one play.

Lafcadio Hearn — Introducing Japanese Ghost Stories to the World

Lafcadio Hearn, a.k.a Yakumo Koizumi, is known for introducing Japanese ghost stories to the world for the first time at the end of the 19th century. Born in Greece, he built up his career in the U.S. as a journalist and then went to Japan with a commission as a newspaper correspondent. He soon fell in love with the country’s fascinating culture and made his home there.

Hearn introduced Japanese culture to the world through his writings, including Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan, Kokoro: Hints and Echoes of Japanese Inner Life, and most notably Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things. Kwaidan was later adapted into the film by Masaki Kobayashi noted above .

If you're interested in Hearn's life, a visit to the Lafcadio Hearn Memorial Museum in Matsue City, Shimane Prefecture is highly recommended. This is where he first settled in Japan and married a local woman, Setsu Koizumi.

Related Stories:

O-CHUGEN: Summer Gift-Giving Culture in Japan

Sacred Traditions Meet Art in Traditional Dancing

“I want you to feel the beat of a live Noh performance.”—The 26th Grand Master, Kiyokazu Kanze