Hike for Hope: A New Long Trail through a Former Disaster Zone

The 200-km Fukushima Coastal Trail takes hikers through some of the heaviest-hit areas of the earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disaster that struck Japan’s Tohoku region in 2011. Tim Hornyak joined trail pioneer Robin Lewis, pro hiker Christine Thuermer and filmmaker Elina Osborne as they hiked around the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant.

By Tim HornyakUnderstanding Fukushima on foot

Looking toward the stricken Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant, now undergoing long-term decommissioning, from the former area of Ukedo.

Ukedo is an area in northern Japan that was home to about 1,600 people on March 11, 2011. Set at the mouth of the Ukedo River, it had a rich tradition of fishing and vibrant festivals where boisterous townsfolk would shoulder portable shrines and dip them in the Pacific. Children swam in the ocean and went to school near the shore. All that changed that afternoon, when the historic, magnitude-9 Great East Japan Earthquake struck the Tohoku region and sent enormous tsunami waves toward the town, breaching a seawall and destroying hundreds of houses. In the area, 154 people lost their lives or were missing and many others lost their homes. Today, nothing is left but one school and a reconstructed Shinto shrine.

The devastating tsunami also overwhelmed the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant 5 kilometers to the south, knocking out its emergency diesel generators and kicking off the failure of cooling systems that led to a deadly, triple meltdown and a large release of radioactive material. As operators struggled to contain the emergency, thousands of people living near the plant along the Pacific coast of Fukushima Prefecture were evacuated.

Walking through the former area of Ukedo, once home to about 1,600 people.

In 2023, people committed to revitalization in Fukushima established the Fukushima Coastal Trail (FCT), stretching more than 200 kilometers along Fukushima’s Hamadori Coast. Aimed at opening up Fukushima to eco-tourism and boosting disaster recovery, it runs from Shinchi Town at the northern border with Miyagi Prefecture down to Iwaki City, on the southern border with Ibaraki Prefecture.

On a recent autumn day, Robin Takashi Lewis was hiking with a group of some 15 people through the town of Futaba in the heart of the FCT. Born in Japan but raised in the U.K., Lewis is a major face of the hiking community in Japan. His site, Michinoku Coastal Trail, is a comprehensive introduction to the 1,000-kilometer-long trail that runs north of the FCT. (You can read about his experiences on the trail here). He believes that an effective way to aid the Tohoku economy and open up the region to travelers is to highlight the allure of coastal hiking, and sees the FCT as going a step beyond Michinoku.

Social entrepreneur Robin Takashi Lewis has been promoting the Michinoku and Fukushima coastal trails to spur recovery in the region.

“I think the Fukushima Coastal Trail is even more off the beaten path than the Michinoku Trail,” said Lewis, “because there are very few people who come here. And if you are interested in the Fukushima nuclear crisis and what’s happening now, there’s probably no better way to learn about it. As you walk you’ll see memorials and meet people and you can piece together what’s happening. Besides that, of course, Fukushima has some really beautiful scenery, regardless of the concrete surface of the route.”

A school stands witness

Heavily damaged in the tsunami, Ukedo Elementary School has been preserved as a monument to the disaster.

Lewis was joined by a group including myself, trail walkers, photographers, YouTubers, a former kickboxing champion, a chemistry PhD and a nuclear engineer, as well as members of the FCT Association (FCTA) and the Futaba Area Tourism Research Association (F-ATRAs), setting out from a rest stop in Namie, for a two-day, 33-km hike through towns decimated by the disaster.

Bordered by cherry trees and wild flowers, the Ukedo River is a relatively untouched natural setting along the Fukushima Coastal Trail.

We set off eastward, toward the Pacific, and were soon walking along the beautiful Ukedo River. Home to egrets and cormorants, the banks are thick with cherry trees and pampas grass, evoking the Japan of ages past. Reaching the remains of Ukedo, 5 km away on the coast, the group came upon the first of several radiation monitoring stations we would encounter, and were surprised to find it showing radiation levels below those of many large cities overseas.

“Never has a trail changed my idea of an area so much,” said Christine Thuermer, a professional long-distance hiker from Germany with over 58,000 km under her belt. “European media portray it as a second Chernobyl, a death zone,” she said. “But you see normal people living here and it’s totally eye-opening. The only way to change your perception is seeing it for yourself, and that’s what makes the Fukushima Coastal Trail so unique.”

Pro hiker Christine Thuermer strides past a reconstruction of Kusano shrine, one of the only structures now standing in Ukedo.

From a seawall at Ukedo, we surveyed the rebuilt fishing port and Kusano shrine. The only structure that remains from the days before the disaster is the ruin of Ukedo Elementary School, preserved as a monument to the tsunami. Even though it is only 300 meters from the sea, all students and staff were safely evacuated thanks to prompt decision-making by the school principal. And yet it is a terribly poignant reminder of the power of nature. Visitors can enter the ruin, preserved as it was on that fateful day, and witness the destruction of the waves, which reached as high as the second floor. They were strong enough to crush most of the heavy equipment in the kitchen into a corner.

First-floor rooms at Ukedo Elementary School have been preserved as they were on March 11, 2011.

Out next stop was in the town of Futaba, at the Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum, 2.6 km from the school. It opened in September 2020 in a large tsunami-hit area that will be redeveloped as the Fukushima 3.11 Memorial Park in the future. Next door is the Futaba Business Incubation and Community Center, a new multipurpose complex with community spaces, a souvenir shop, a convenience store and some restaurants including Sendantei specializing in delicious Namie-style yakisoba, a Japanese “B-class gourmet” comfort food favorite prepared with extra-thick noodles, pork belly and bean sprouts in a rich Worcestershire-style sauce.

Sendantei specializes in delicious Namie-style yakisoba, a Japanese “B-class gourmet” comfort food favorite made with thick noodles and pork belly.

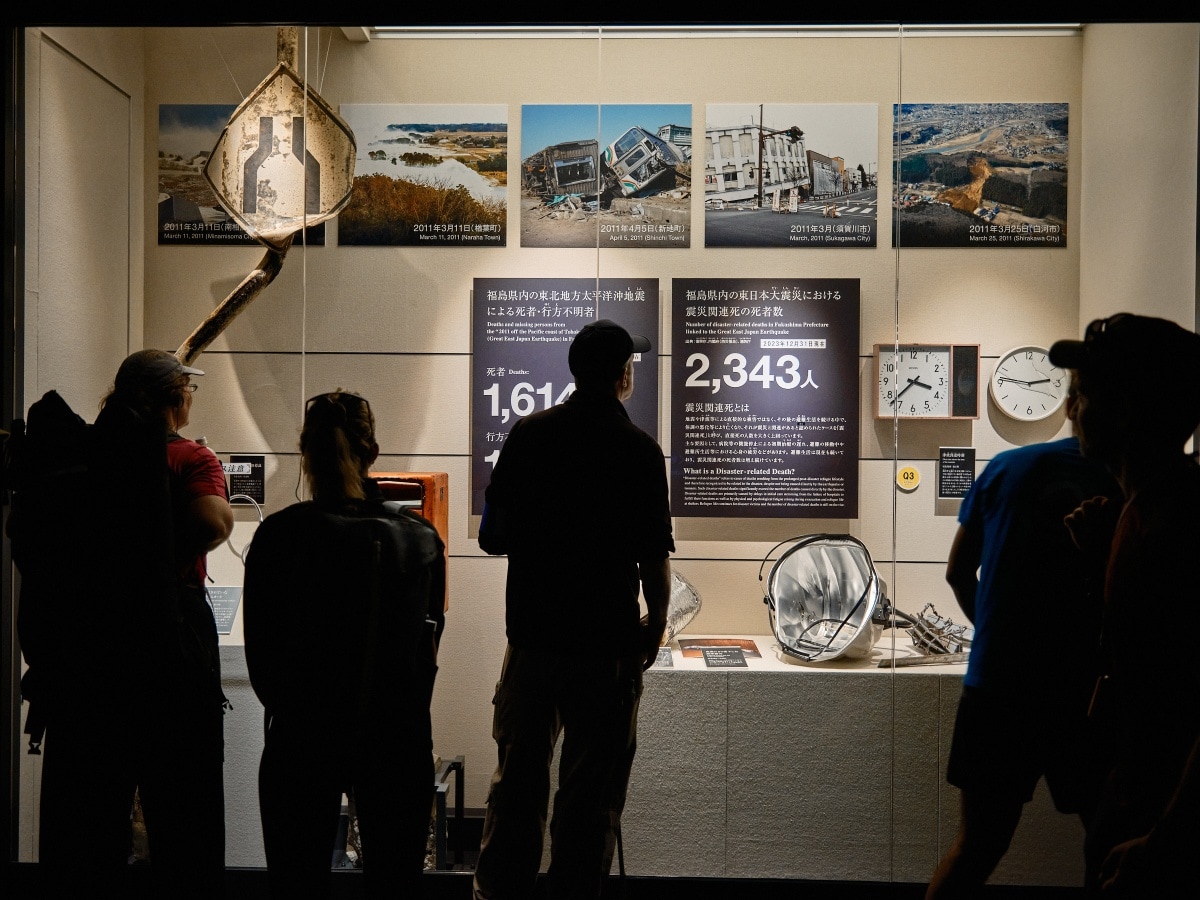

With its archive of 290,000 artifacts, the expansive disaster museum is a comprehensive site dedicated to the cataclysm of 2011, with exhibits on the quake, tsunami and nuclear meltdowns, as well as local history, decontamination efforts, robotic tools and untold stories of the crisis. Visitors can learn, for example, about how 200 workers toiled day and night to prevent a further catastrophe at Fukushima Daini Nuclear Power Plant by installing 9 km of temporary cable to supply emergency electricity to the cooling system. Some of the most poignant exhibits include video testimonials and news photos of people fleeing the crisis, burying the dead, and surveying their shattered homes.

Opened in 2020, the Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum (top) has exhibits on the quake, tsunami and nuclear meltdowns (middle, bottom), as well as local history and decontamination efforts.

Rekindling a community through art and entrepreneurship

Tokyo-based art group Over Alls has turned buildings in the devastated town of Futaba into signs of hope.

We continued inland toward JR Futaba Station, at the heart of the town that was evacuated in the disaster; residents began returning only in 2020. En route, we came upon a series of vibrant murals that make up the Futaba Art District. These are larger-than-life paintings, some more than 10 meters across, by Tokyo-based art group Over Alls that fuse themes related to Futaba’s past with hopes for its rebirth. The town’s now-ironic signboard that promoted nuclear power has been replaced with a building-sized mural of smiling people wearing traditional hachimaki headbands under the words “human power.” Others depict emergency workers girding themselves for battle in the style of samurai or, painted on an abandoned public library, a giant neon Daruma doll, a traditional decoration expressing hopes about the future, that seems to crackle with energy. The artworks are a powerful symbol of the community’s resolve to rebuild, virtually from scratch.

The Over Alls murals have replaced Futaba’s now-ironic signboard that promoted nuclear power.

From Futaba Station, we drove south to the town of Okuma, where some 866 people live now (as of October 2024), far fewer than the 2010 population of 11,500. After spending the night at Hotto Okuma, a recently built hot spring inn, we set off for JR Yonomori Station, some 6 km to the southeast. The route passed many abandoned buildings and farms before a stop at an inspiring startup business: Yonomori Denim. Local entrepreneur Sho Kobayashi survived the earthquake, which struck on the day he graduated from junior high school. After working for an apparel company in Tokyo, he decided to set up Yonomori Denim to help revive his deserted hometown. He buys preowned jeans from overseas, repurposes and resells them in Japan, sometimes adding quirky extras like fabric from discarded kimono. There may be few residents in the area, but Kobayashi’s business is slowly growing, breathing new life into the local economy.

Sho Kobayashi founded Yonomori Denim to help rebuild his hometown in the former evacuation zone.

Lewis (left) and fellow hikers check out Yonomori Denim’s refurbished jeans.

Yonomori Denim produces denim handicrafts out of used Levi’s jeans.

The final stretch of the hike covered the 13-km distance to JR Tatsuta Station. We broke for lunch at Fukinoto, a seaside restaurant and inn within sight of the towers of Fukushima Daini Nuclear Power Plant which, like its Dai-ichi counterpart, is being decommissioned. We wound up our jaunt, some with sore legs and feet, with coffee at Café Yadorigi by Tatsuta Station, where we reflected on everything we saw and people we met over the two days.

Opened by a couple from Tokyo (middle), Fukinoto restaurant looks out over the waters around Fukushima Dai-Ni Nuclear Power Plant (top), where waves crash against the wreck of a tsunami-tossed ship (bottom).

A statue of the bodhisattva Jizo, a guardian deity of children and travelers, stands by a road in Futaba.

Thuermer, filmmaker Elina Osborne, and Lewis share thoughts about the Fukushima Coastal Trail at Café Yadorigi by Tatsuta Station.

“The best way to understand the local people is to walk the land,” said Elina Osborne, a filmmaker and hiker from New Zealand who has walked the Te Araroa Trail, the Pacific Coastal Trail, the Kumano Kodo Trail and many others. “People who come here can see how it’s so much more than the disaster and it’s forming a new identity. What makes the Fukushima Coastal Trail unique is that it’s mainly an urban trail, not a nature trail, and so you come to understand the people and the culture. Those two together make it special.”

Lewis summed up the feelings of many of us. “You gain things here that you cannot gain up on the Michinoku Trail,” he said. “You learn about how everything unfolded and the failures and successes of the disaster. Ultimately, the trail is a vehicle for bringing people together.”

Photos by Hitoshi Tayasu