Eating and Drinking the Back Streets of Nara

The stately timber premises of Unagiku reflect its status as the finest unagi (eel) restaurant in Nara. Inside and out, little appears to have changed since the19th century. All photos by Robbie Swinnerton.

There are many ways you can approach Nara. As Japan’s first and oldest capital, it has historic artifacts, religious sites and traditional culture to rival anywhere in Japan. But to truly grasp its character and the laid-back charm of this ancient city, try slowing down, spending a few days--and nights--exploring the rich cuisine of its backstreets.

By Robbie Swinnerton

The atmospheric low-rise backstreets and narrow alleys of Naramachi are perfect for leisurely exploring, with numerous shops, restaurants and drinking establishments to discover.

Nara has a quiet, slow-paced charm that contrasts markedly with the big-city bustle of either Kyoto and Osaka. And because it lies so close to both, less than an hour by road or train, it can easily be slotted into the busiest tourist itinerary as a day trip.

From the station you can stroll to the beautiful public park with its free-roaming herds of sacred sika deer, view the Great Buddha and other World Heritage sites, have a light lunch, take in the scenic Sarusawa Pond (though sadly the nearby five-story pagoda is now hidden from view for renovation); and still be back at your hotel in the city in time for tea.

The grid of streets that comprise Nara’s old town—the bottom-left segment on this ancient map—developed on land that was originally owned by Gengo-ji, a Buddhist temple now recognized as part of the city’s World Heritage listing.

And that’s how I’ve done it on numerous occasions, usually while guiding jet-lagged family or business visitors around Japan. This time, though, I’m back in Nara together with my wife, and our focus is quite different. We’ll be staying a couple of nights and our schedule will be low-key, leisurely and strictly secular. No temples, no queues for souvenirs, no scavenging cervids.

We have come to relax, explore and, most importantly, to eat and drink our way around some of the best restaurants, sake taverns and bars in Nara’s atmospheric old town, a grid of low-rise backstreets and narrow alleys unofficially known as Naramachi.

It will not be all freeform and spontaneous. We’ve made a couple of necessary bookings ahead of time but we’re also giving ourselves plenty of leeway to just wander around, stopping to poke our heads into anywhere we like the look of. Naramachi is the perfect place for that.

All Aboard!

Kintetsu Railway’s deluxe Aoniyoshi sightseeing service between Kyoto and Nara boasts a bar well stocked with snacks and beverages, including ales from Kintetsu’s own craft beer company, Yamato Brewery.

We start the way we mean to continue — on the train from Kyoto. Kintetsu’s deluxe four-car Aoniyoshi sightseeing service only runs four times a day in each direction but it’s well worth the modest surcharge (¥900 each, prior booking required).

It covers the 40 kilometers between the two capitals in just over 30 minutes. But that’s enough to avail ourselves of the snacks and beverages offered at the in-train bar — including a choice of two draft ales on tap from Kintetsu’s own craft beer company, Yamato Brewery.

At Stand-bar Mutsuki the sake is plentiful and cheap. Like many of the drinking holes in Naramachi, it opens early and fills fast.

By the time we arrive at Kintetsu-Nara station we are ready for action. From there it’s just a short stroll down into Naramachi. First stop: Stand-Bar Mutsuki (24-4 Tsunofuricho, Nara), where the sake is plentiful and cheap but no one outstays their welcome since (as the name makes clear) there is no seating.

As in so many tourist towns where the majority of visitors are day-trippers, Nara’s drinking holes open early and fill fast. By noon, Mutsuki is already busy and smoky. But we’re happy to prop up the outdoor counter by the front door, enjoying the people watching as we sip and plan our strategy. We’re only there to wet our whistles. The main order of business for this afternoon lies further down into Naramachi.

The vicinity of the station is the most filled with tourists, both domestic and from overseas. From there southward, the land dips and then rises again, up to the quieter, more traditional residential parts of Naramachi. It is the area in between, the bustling shopping streets on either side that has the main concentration of shops and restaurants can be found. That’s where we’ll be heading next.

My Sort of Place

Housed inside a converted storeroom built 130 years ago, Sakedokoro Kura is a classic, old-school izakaya that attracts fans from far and wide in Japan. With limited seating and no reservations taken, you just have to wait your turn outside.

I first chanced upon Sakedokoro Kura (16 Komyoincho, Nara) a couple of years back, after finishing up a job elsewhere in the city. It was closed that day and there were no clues for me to gauge whether or not it was of interest. But the bold red kanji of the name called out to me, mysterious and alluring. This was backed up by the sign outside the door: "Cold sake and (hot) oden." It definitely felt like my sort of place. Now, finally, I have returned to to see what it looks like inside.

The name is doubly apt as it immediately whispers of sake — in Japanese, breweries are known as kura. But it also describes the edifice itself, a converted traditional storeroom (the same word kura) originally built 130 years ago for a kimono dealer.

Besides its year-round specialty, oden hotpot, Sakedokoro Kura serves a good range of seasonal side dishes to accompany the selection of local sake.

Sakedokoro Kura specializes in local sake made within Nara Prefecture—including some from the Harushika brewery inside Naramachi.

The atmosphere is palpable, almost as if you’ve walked into a chapel. Everyone keeps their voices down, at least until they’ve had a few drinks. Just about all the sake is from from local companies: Kaze no Mori and Shinomine are from elsewhere in Nara prefecture; and Ura-Harushika brewed right in the town. They pair beautifully with the oden that owner Horiguchi-san and his wife prepare each day.

Like us, most of the other customers are out-of-towners. But as spots at the counter free up, local regulars start to drop in. They seem happy that people come from so far to drink in their neighborhood and are clearly proud of the seasonal local delicacies at Kura.

When we order a serving of bamboo shoot from the oden pot, my neighbor suddenly heads out of the door, returning five minutes later with a sprig of kinome (spicy sansho pepper leaf) in his hand. It turns out he plucked it – with permission of course – from a nearby garden. Why? Because it was inconceivable to him that we should eat our bamboo without the requisite yakumi herbal seasoning.

Kura is that sort of place. In fact, as we repeatedly find over the next two days, the same goes for pretty much all of Naramachi. It’s a far cry from the metropolitan aloofness of Tokyo or the nose-in-air insularity too often encountered in Kyoto. Lubricated as much by the camaraderie as the sake, we take our leave.

A Cut Above

The piece de resistance at Unagiku is unagi kabayaki — eel that is filleted, broiled and basted with a thick sweet-savory soy sauce. Unusually, it is prepared in the Edo (Tokyo) style, steamed before it is broiled for an extra fluffy lightness.

We are off to Unagiku. Not only is it the best unagi (broiled eel) restaurant in town, it has a peerless pedigree. Built in 1891, the stately timber premises dominate the skyline above Naramachi, abutting the deer park on one side and the equally patrician Nara Hotel on the other.

We have reserved our table ahead of time but the building has so much space on multiple floors no one seems to be turned away for lack of a booking. A kimonoed matron ushers us along well-polished passageways, up several flights of stairs and into a room barely changed since the19th century, except it has vintage tables and chairs rather than cushions on tatami mats.

At Unagiku, the grilled eel is always prepared to order, a process that can take half an hour. While you wait, it’s well worth ordering a few of the classic starters, such as unagi-yubiki, lightly parboiled eel served with a miso-vinegar sauce.

We order an abbreviated version of the full banquet, nibbling on side dishes such as uzaku (eel morsels with rice vinegar dressing) and shirayaki (eel grilled "white," without soy basting sauce). Finally our main course arrives: unaju, broiled eel basted with thick, sweet kabayaki sauce and served on rice in lacquer-look boxes.

What’s notable here is that the unagi is cooked in the Edo/Tokyo style, steamed before being grilled to give a lighter texture. The eels are kept alive until each order comes in. That’s why your meal takes time to prepare.

Setting, ambiance, flavor: Unagiku is a cut above.

In historic Naramachi, Chami stands out as a thoroughly contemporary third-wave coffee specialist. Along with the best espressos and flat whites in the city, Chami also serves a range of gorgeous patisseries.

Not everything in Naramachi is old. Morning finds us in line outside Chami, a thoroughly contemporary coffee roaster and dispensary in the minimal Bluebottle mode. Along with the flat whites and pour-overs, Chami also offers a gorgeous array of patisseries of serious quality. We opt instead for the "herb dog," a superior wiener accented with aromatics and served in a real hot dog bun.

Thus fortified, we make our way up the slope, heading for the farther end of Naramachi. The residential streets there are much quieter than those closer to the station. We walk past a Buddhist temple, Gengo-ji, that once owned all the surrounding land. Though much diminished in size, it is still recognized as part of the city’s World Heritage listing.

A major focal point of the area now known as Naramachi is Imanishi Seibei, producer of Harushika ("Spring Deer") sake. To this day the brewery remains family-run and visitors are welcome to look around, view the traditional processes and even sample and buy the wares.

A Soba Pilgrimage

Simple but perfect: the artisan soba noodles at Gen are hand-made each morning by owner-chef Hiroyuki Shimazaki. He prepares the exact amount of servings for the customers with reservations, so you need to specify how much you want to eat when you book.

Today, though, it is not alcohol but noodles we are searching for. Nara’s best-loved artisan soba restaurant, simply called Gen (pronounced with a hard "g"), lies close by. Housed inside a beautifully restored, single-story, wooden villa right next to the brewery, it was formerly the owner’s residence but had fallen into considerable disrepair by the time chef Hiroyuki Shimazaki and his wife took it over 35 years ago.

These days it has become an object of pilgrimage for aficionados of artisan buckwheat noodles. In the evening, Gen serves a multi-course Soba Yuzen set dinner. But at midday the a la carte menu is much simpler.

Before your noodles arrive, there are outstanding appetizers to try, especially the soba-dofu, small soy-milk custards with savory toppings such as uni (sea urchin).

Gen occupies a beautifully preserved single-story wooden villa that was formerly the residence of the owner of the Haruchika Brewery but which was in disrepair when chef Hiroyuki Shimazaki and his wife took it over 35 years ago.

There are a few appetizers to pair with sake (from next door, of course) — the highlight being the soba-dofu, small tofu-like custards resembling panna cotta with savory toppings such as uni (sea urchin), mentai (spicy cod roe) or yuba (tofu skin). But the main event is the soba, served cold on a bamboo tray.

Each day Shimazaki makes two different kinds of noodles: light seiro soba or thicker, chewier inaka (country style) soba, each of which are served cold with a selection of dips and condiments. True connoisseurs first taste their noodles simply dipped in well water — the same water used by the brewery next door — to appreciate the light, nutty flavor of the buckwheat grain.

Gen does have an English version of its menu. But when you phone to reserve your seat, which is essential, you will be asked in advance (in Japanese) how many of each soba you wish to eat, so that Shimazaki will prepare exactly that number of servings. For most people, one of each kind should be adequate.

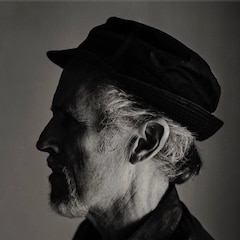

Food writer Robbie Swinnerton stops off for refreshment at one of Naramachi’s many sake shops, where the seating is a still-viable truck used to ferry the wares from the street to the storerooms further back.

Before leaving Nara, we have plenty more sake to drink, dishes to visit and meals to look forward to. We will also be searching for a few favorite local delicacies to take back to Tokyo with us.

En route to the station, we make a detour to Hirasou to pick up supplies of kakinoha sushi — two-bite oblongs of pressed sushi rice topped with fish, each wrapped in a single semi-dried persimmon leaf. This busy backstreet restaurant is widely considered by locals to prepare the best kakinoha sushi in town. The light, lingering flavors help to keep alive our taste memories of Naramachi long after our shinkansen has departed Kyoto.