Hiking Tokyo’s Active Volcano: The “Sacred Fire” of Oshima Island

The crater of Mt. Mihara, whose last major eruption in 1986 spewed plumes of ash and debris into the air, forcing the evacuation of many residents.

Mt. Mihara is an active volcano on an island just outside Tokyo Bay, with a fascinating history, superb seafood, hot spring baths, and friendly local residents. While it’s possible to climb the peak on a day trip from central Tokyo, think about staying overnight to experience the island’s unique offerings. Photos by Maki Starr and Gregory Starr.

By Gregory StarrIT'S NOT A BAD WAY TO start the day. Every morning, from our home on the coast of the Miura peninsula, an hour south of Tokyo, we’re greeted by the sight of two active volcanos. To the west, some 70 kilometers across the broad expanse of Sagami Bay rises Mt. Fuji, the appearance of its iconic cone shifting with the weather and the seasons, even the time of day.

Southward, 55 kilometers away on the opposite edge of the horizon, is the island of Oshima, the first of the Izu chain of seven islands administered by Tokyo. The island’s crowning feature is the volcanic peak of Mt. Mihara, which last erupted in 1986, forcing the evacuation of hundreds of residents and sending a towering plume of ash into the sky—some of which drifted as far as the fishing village where we live.

While Oshima’s squat silhouette struggles to compete with Fuji’s perfect form, its constant presence eventually led us to plan a visit to our “second volcano.” What intrigued us most was the chance to hike the caldera even in winter, and without the crowds that throng Fuji’s slopes. It also helped that the island is accessible via a one-hour hydrofoil cruise from the nearby port of Kurihama on one of the Tokai Kisen ferries. (From central Tokyo, it’s a two-hour trip.)

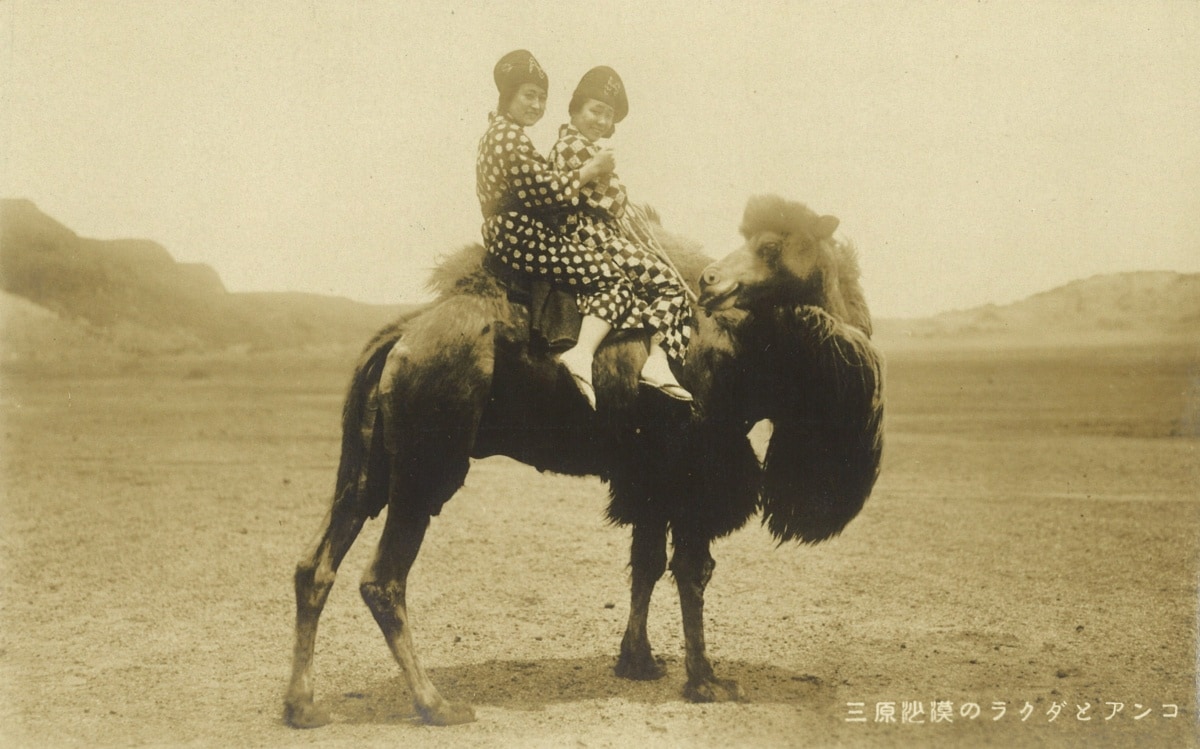

Two young women at the pier, dressed in the traditional checkered kimono and headgear of anko-san, local Oshima women who would sell goods and entertain visitors to the island.

SO IT WAS STILL MID-morning on a calm, sunny winter day when we arrived at the port of Okata, one of the island’s two ferry terminals. For over a thousand years, until 1766, the island was used as a place of exile. Among those banished here were relatives of fallen warlords, imperial family members, Christians, rebellious samurai, even some of the 47 ronin who famously avenged their lord’s death in 1703 before being forced to commit suicide.

The crowd of passengers disembarking the day of our visit were a happier bunch, a mix of tourists, locals and visiting businessmen streaming into a modern terminal that houses souvenir shops and a small restaurant. We passed up the sushi and curry dishes and grabbed a few onigiri rice balls before sprinting for our bus.

Trekking in the Footsteps of the Anko-san

Anko-san in front of the Utanochaya tea house during the tourism peak in the early Showa era. Many tea houses lined the trail at the time, but Utanochaya is the only one still operating (Photo courtesy of Oshima-machi)

THIRTY MINUTES LATER, WE arrived at the Mt. Mihara observatory, the starting point for the summit trail. We passed the Utanochaya tea house, the last remnant of a teahouse culture that thrived for many years, particularly in the early Showa period (1926 – 1989). Back then, some 10 teahouses lined the route up from the port, where the ladies known as anko entertained visitors with singing and dancing along with views of the volcano. The anko also carried goods on their heads as they trekked up and down the trail, selling walking sticks and sandals, camelia oil, mandarin oranges and other fruits to the visitors. According to a local, climbing Mt. Mihara was so popular that the line of hikers stretched from the wharf to the peak, with camels and donkeys imported to add an exotic flair.

The stone monument marking the trailhead to Mt. Mihara, just past the observatory and the last teahous

Those heady days are long gone. There were few visitors the day of our hike, and we had much of the trail to ourselves. Two routes lead to the summit from the observatory: a paved road and a path through the lava fields. Both are steep in sections but not too strenuous. We chose the unpaved route, which meanders over fine lava sand, grassy areas, gravelly patches and rugged stretches strewn with jagged rocks. Once at the summit, a 2.5-kilometer unpaved circuit of the volcano’s caldera offers breathtaking views—not only into the crater but stunning panoramas in all directions: Mt. Fuji to the north, the two peninsulas of Izu and Chiba peninsula to the west and east, and the perfectly pointed cone of Toshima and the other Izu islands to the southwest.

Onigiri rice balls from the harbor terminal were a perfect lunch, light, flavored with the ashitaba herb, along with takuan pickles. The torii gate in the background is the entrance to the path down to Mihara Shrine.

The torii gate of Mihara Shrine, with the snow-capped Mt. Fuji in the distance across Sagami Bay.

Gojinka: The Sacred Fire at the Heart of Oshima

From the summit: the perfect cone of Toshima, the second in the Izu island chain, with the other islands stretching out in the distance.

WE PAUSED FOR A LUNCH OF onigiri from the harbor shop, then passed through the torii gates to visit Mihara Shrine, which miraculously survived the 1986 eruption. A ridge of hardened lava just above the shrine split the approaching lava flow, diverting it around the building before it merged further down the slope. Continuing around the caldera rim, we saw more reminders that this is still an active volcano: large clouds of steam rose from fissures in the ground, wafting over us before dissipating in the wind. There is a line from a famous folk love song that goes, “I was raised by Oshima’s sacred fire, smoke forever rising in my heart.” The “sacred fire”—gojinka—is what the Oshima people call their mountain, and I wondered how it must feel to live in the shadow of such a revered yet potentially dangerous force, and turning what could be seen as ominous into a romantic symbol.

The highest point of the Mt. Mihara volcano, at 758 meters.

The trail around the rim is narrow but well marked. Sturdy shoes help avoid twisted ankles and slipping.

Clouds of steam emerge from fissures in the rocks at various places around the crater, a mark of the still active situation of Mt. Mihara.

We wondered why part of the map was marked Texas Route until we arrived at this section of the trail.

We chose to skip completing the full loop around the crater rim, and instead descended to Miharayama Onsen, a hot spring hotel at the foot of the northern slope. The path took us down the aptly named Texas Route, and once the trail leveled off, it did resemble something out of the Old West, with craggy rock outcrops jutting out of the sandy lava and clumps of low grasses stretching all the way to the horizon. Sadly, we didn’t encounter any donkeys or camels, but we did find marked posts to guide hikers caught in foggy weather. Just a few kilometers short of the hotel, the trail entered a dense forest of low-growth Japanese holly trees, dotted here and there with cherry trees that add color to this muted landscape in the spring.

Hot Spring Panoramas and Oshima Delicacies

The community mixed bathing outdoor bath called Hama-no-yu sits on a plateau over the port town of Motomachi, with Sagami Bay and the Izu peninsula in the background. It's a luxury experience for only ¥300. (Photo courtesy of Oshima City office.)

FROM THE HOTEL, WE BUSSED back to Okata Port and on to Motomachi, the island’s larger harbor town. After checking into our guest house, we made the short walk to Hama-no-yu, a community open-air hot spring bath perched above the port area. The large pool is open to mixed bathing, so swim suits are required. At ¥300 it is a more than a reasonable luxury. We joined the few locals, and sank up to our necks in the hot water as the sun dipped low in the sky, sending a shimmering golden ribbon across the sea.

Once refreshed, we found ourselves at the counter of Uminosachi, watching chef Takayoshi Ishizawa select slabs of fresh fish from the glassed cooler in front of us before going to work with his sashimi knife. There was maguro, and mackerel, and akagai shellfish, but we followed his suggestion and ordered sabi, a fatty, white-flesh deep-water fish that is a local specialty. It came Oshima-style, with aotogarashi, an aromatic tear-inducing green chili, in place of the usual wasabi garnish. Ishizawa bustled back and forth from counter top to the kitchen, serving a full house while sharing stories of his years running the restaurant, the struggle to keep Oshima’s young people from leaving, and the island’s culinary traditions.

Chef Takayoshi Ishizawa plied us with Oshima delicacies and regaled us with tales of his life on the island of Oshima.

Sashimi slices of sabi, a deep-water fish that I've never seen elsewhere, served Oshima-style with aotogarashi green chillis instead of wasabi.

Ashitaba (lit. tomorrow's leaf) is an herb that believers claim can help with heartburn, ulcers, high blood pressure and many other problems. At Uminosachi, it was sauteed with a local seaweed.

Among other dishes Ishizawa suggested to go along with the local Oshima shochu (served mixed with hot water and a slowly dissolving pickled plum) was the ashitaba sauteed with seaweed. Ashitaba, “tomorrow’s leaf,” is an herb used to treat various health conditions—such as high blood pressure—but it’s also a tasty leaf that appears on many Oshima menus, including in the rice balls we had for lunch. We ended the meal with chilled local mikan citrus in gelatin. (While we were lucky to stumble across this popular izakaya and get seated, reservations are recommended. Motomachi 4-10-3, Phone: 04992-2-2942)

WHY STAY ON A VOLCANIC island if you don’t make the most use of its blessings? After dinner, we rushed to get to Ailando Center, another community hot spring, before closing time. I soaked in the jacuzzi, massaging tired muscles while exchanging information about what to do the next day with a lively group of locals and visitors. What I forgot to ask about was the weather.

We’d planned to cycle the island’s ring road before our scheduled ferry, but woke up to high winds blustery enough to discourage that idea. While gorging on the “morning set” at the wonderfully eccentric Momomomo coffee shop, we learned that our high-speed ferry home had been cancelled due to high waves. So we adjusted our plans, booking an earlier, larger (and slower) conventional ship, and rented a car to explore the island. We had just enough time for a brief circuit, stopping at the small fishing port of Habu for a sushi lunch featuring the local catch.

Harbor Entertainment: The Dancing Girls of Habu

Just above Habu port stands the old inn Minatoya, now the Odoriko no Sato (Home of the Dancing Girl) Museum.

This could get spooky at night. This inn (now a museum) dates from the heydays of Habu port, and though unattended is populated with full-sized dancing girls, musicians and sake-quaffing customers.

HABU WAS ALSO THE HOME port of the traveling dancers in Kawabata Yasunari’s short story The Dancing Girl of Izu. The story’s protagonist, the young dancer Tami, would be hired by guests to perform at local inns like the Minatoya Ryokan, now a museum. The building shows signs of its age, but the traditional architecture is impressive and reeks of a prosperous past. The museum is free of charge, its dusty entrance unstaffed, but someone has gone to the trouble of populating the rooms with full-size dolls of guests, musicians, and dancers in various poses. It was startling at first and a bit spooky, given the emptiness of the old inn when we walked through. In one room, an animatronic trio of women in kimono jolted into action at the push of a button, playing instruments and dancing in a silent, nostalgic pantomime. I glanced back through the window at the fishing boats rocking in the harbor, and imagined the Showa-era fishermen rushing to offload their catch and hightail it to the inn for a night of sake-fueled entertainment, still smelling of the sea.

Mt. Fuji is a constant presence, even at the port as the ship prepares to depart for Tokyo.

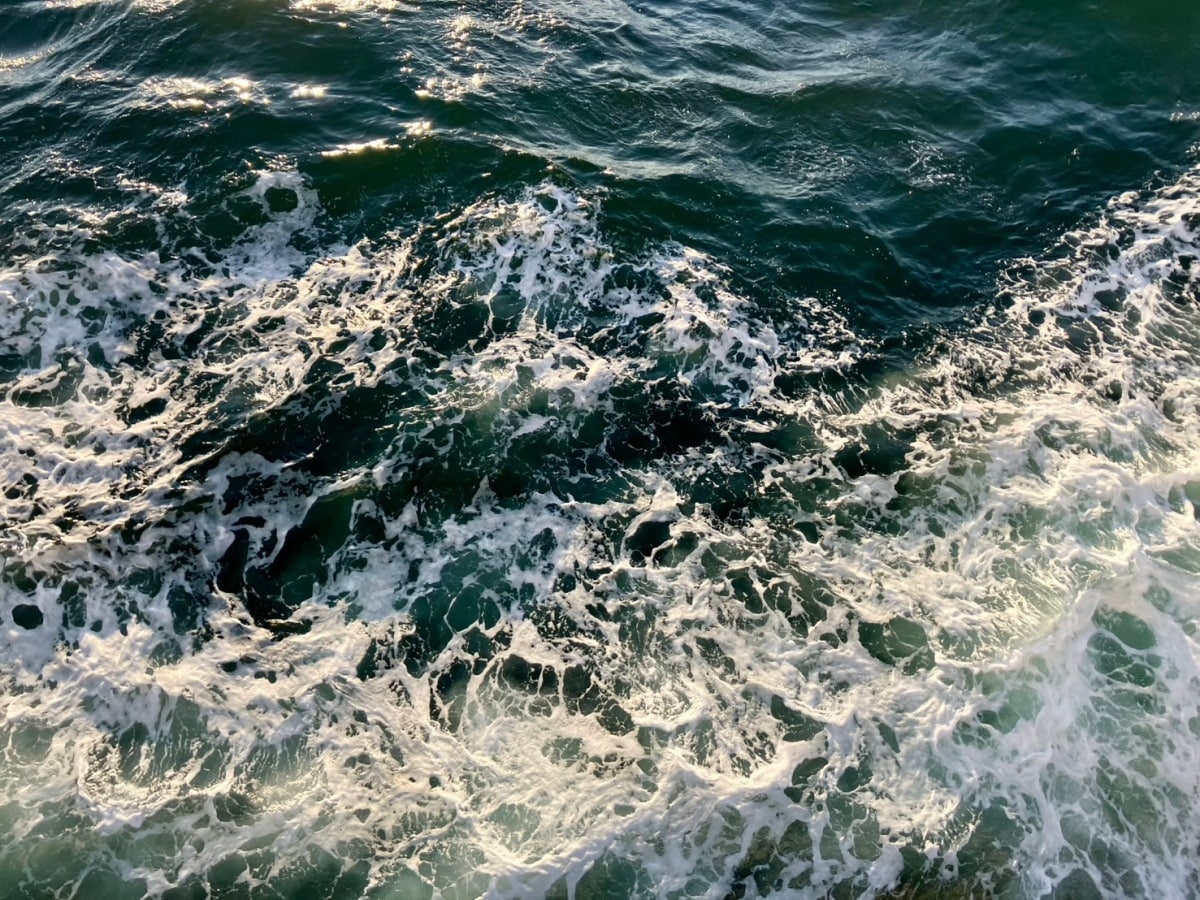

WE MADE IT BACK TO Okata port just in time to return our rental car and grab snacks before boarding the large liner to Tokyo. The ship was immaculate, and our second-class seats were the equivalent of business class—upholstered in plush “leather,” well-padded, with pull-down curtains, fold-out tables and padded footrests. Despite the rough seas, the ride was smoother than a jet, and we didn’t even notice the ship leaving the wharf. There were clean showers, a bustling restaurant, and vending machines selling everything from frozen dinners to alcoholic drinks (a Japanese driver’s license must be inserted to confirm your age). The comfort was welcome, as the one-hour trip to the port near our home had turned into a five-hour cruise to central Tokyo. But it was hard to stay disappointed. We spent our time watching the wake and the sunset, once again with Fuji’s silhouette in the distance.

It was dark by the time we arrived, and the buildings of Tokyo’s skyline were ablaze with lights, their reflection in the bay marking our approach to the berth at Takeshiba Pier. We stumbled off the boat and were quickly caught up in the rush to the nearby station. We got home late, but energized by our time away. I aimed a pair of binoculars at Oshima, and could just make out a faint outline of the island and its mountain, along with a few lights flickering where the harbor must be. Our southern volcano seems much closer now.

In the heady days of early Showa, donkeys and camels were introduced to the lava fields of Mt. Mihara, adding an exotic touch. (photo courtesy of Oshima-machi).