Japan's Himekuri Calendars: Amazing Almanacs

Even though Japan adopted the Western Gregorian calendar about 150 years ago, it continues to draw inspiration from its premodern time system and its links to natural phenomena and traditional events. One example of this is the perennial popularity of himekuri calendars.

By Tim HornyakTurning the page

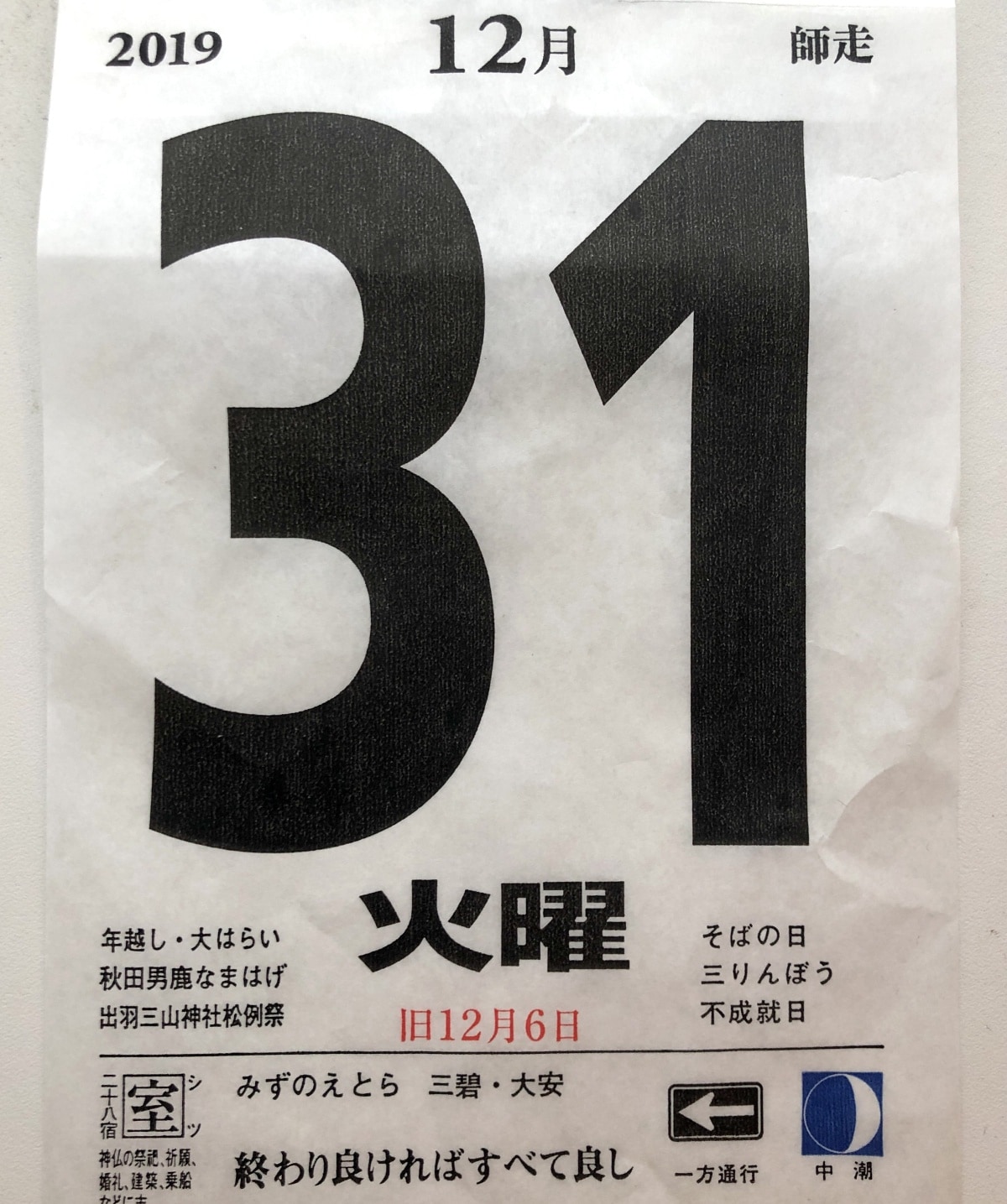

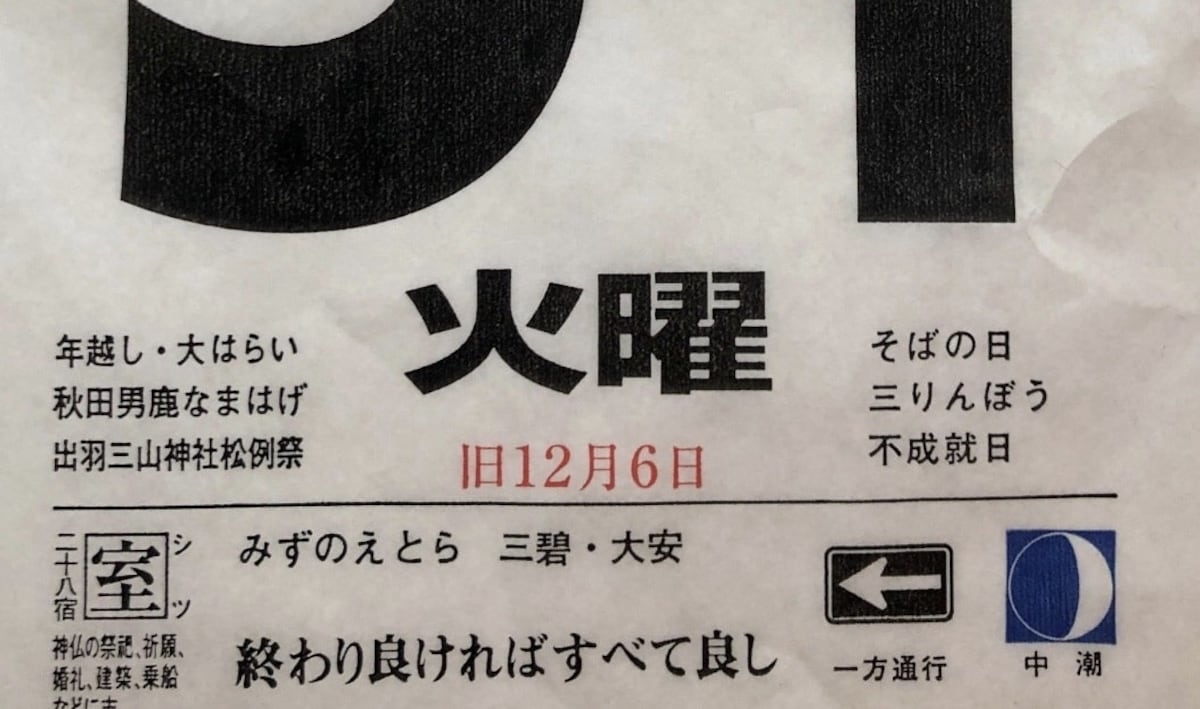

A typical page of a traditional himekuri calendar is full of facts and information. The various entries are explained below.

Himekuri calendars are similar to page-a-day calendars seen in other countries, but they’re chock full of things to learn and remember about the Japan of today and yesteryear. In that sense, they’re like compact Japanese almanacs that can hang on your wall on stand on your desktop.

Published by Ise Shrine, one of Shinto’s most sacred sanctuaries, calendars first appeared in Japan during the Meiji period, when Japan began turning the page on centuries of feudalism. According to Ract Co., a calendar publisher in Hiroshima, himekuri were first produced in Osaka in 1903, 30 years after Japan switched to the Gregorian system. They were often made as promotional items for local businesses and distributed in vast quantities to their customers. Himekuri were only overtaken by monthly picture calendars after the U.S.-led Occupation beginning in 1945. A renaissance began in the 1980s, however, when PHP Institute started publishing himekuri calendars containing maxims attributed to Panasonic founder Konosuke Matsushita.

So what is special about himekuri? Their combination of old and new. Let’s dissect the page above from December 31, 2019. Sandwiched between the words for “December” and “Tuesday,” a boldfaced “31” dominates the page. But it’s surrounded by all kinds of nuggets of information. In the top right corner is shiwasu, the traditional Japanese term for the last month of the year. Shiwasu literally means “running priests,” denoting all the preparations that monks have to make for the New Year. Japan’s traditional names for the 12 months have seasonal associations, such as Uzuki, or “the month of u-no-hana” or Deutzia flowers, for April, and Hazuki, or “the month of leaves,” for August.

Printed in red below “Tuesday” is the kyureki, the day and month of the traditional calendar: December 6th. On either side of that are events and observances taking place across Japan. For instance, the Shoreisai festival at Dewa Sanzan Shrine is held on New Year’s Even atop Mt. Haguro in Yamagata Prefecture and involves the burning in effigy of a demon that, according to legend, terrorized the community long ago. Another observance noted on the page is Soba Day, a time to tuck into toshikoshi New Year’s soba, symbolizing a severance from the hardships of the past year.

All in a Day

More info, from fortune telling to traffic signs and lunar phases.

At the bottom of the page are even more nuggets. On the left is a box containing the kanji 室 (room or cellar) and a reminder of how to pronounce it. Below and to the right of that are indications of the rokuyō, a repeating cycle of six days that are used for fortune telling. Rokuyō are believed to have been imported from China in the 14th century, and although the Meiji government tried to stamp the system out as a superstition linked to onmyōdō divination, they are still used to this day to plan important events. For instance, on our himekuri calendar, December 31 is a day of taian, or great peace, considered a most auspicious day for new endeavors such as getting married; the page also notes that it’s a good day for take a boat trip. The page also notes that December 31 is mizunoetora, part of a complex traditional Chinese method of numbering years and days that is also known as the Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches or the sexagenary cycle.

Rounding out the page at the bottom and in the lower-right corner are an aphorism, which could be translated as “all’s well that ends well,” and some practical information: the current moon phase and a reminder about how to recognize one-way road signs.

"Some feature cartoon characters like Hello Kitty or simply images of cats and dogs."

A popular himekuri calendar on sale at a local book store.

These days, himekuri calendars come in all kinds of formats. Some are more traditional and are attached to cardboard backing promoting manufacturers or other businesses. Some are endorsed by Japanese celebrities like former tennis pro Shuzo Matsuoka or the late Buddhist nun Jakucho Setouchi. Others feature cartoon characters like Hello Kitty or simply images of cats and dogs. Publisher Fusosha even produces a calendar that purports to help users improve their eyesight with vision exercises. Not a few carry inspirational maxims to give owners an energetic boost.

Next time you come across the calendar section in a Japanese bookshop, check out the himekuri. For everything from lucky days to aphorisms and kanji and road sign refreshers, they’ve got you covered.