Racing to the Future: Accessibility in Japan

With the 2019 Rugby World Cup on the horizon and the 2020 Tokyo Olympic & Paralympic Games shortly after, Japan is working hard to develop and implement strategies for creating barrier-free environments at sporting venues and tourist destinations around the country. Kyushu's Oita Prefecture is ahead of the curve, and a model on which to improve.

By Nicholas Rich

https://pixta.jp

As Japan enters the final stages of preparations for the 2020 Olympic & Paralympic Games in Tokyo, the government aims to attract some 40 million inbound tourists. With the anticipated deluge of international visitors to Japan's densely populated capital city (and the country as a whole), greater emphasis is being placed on accessibility, and the creation of a barrier-free travel environment. Education initiatives and comprehensive implementation of multilingual support aims to break down the language barrier visitors face, but what about physical barriers that might impede people with disabilities?

I had the chance to join the Japan National Tourism Organization and the Tokyo Organizing Committee of the Olympic & Paralympic Games on a media tour of Oita Prefecture, a shining example of how to successfully create a barrier-free environment.

https://pixta.jp

Oita Prefecture is tucked away in the northeast corner of Japan's southern island, Kyushu. Surrounded by mountains on one side and the Seto Inland Sea on the other, Oita is perhaps best known for the city of Beppu, a gorgeous onsen resort area that boasts the second largest volume of natural hot spring water in the world. The capital of Oita is a city of the same name, a populous metropolis that hosts a variety of national and international sporting events throughout the year, including the annual Oita International Wheelchair Marathon.

The Oita International Wheelchair Marathon began in 1981 in commemoration of the International Year of Disabled Persons. 2018 marks the 38th iteration of the event (which you can read our write up of here), and in the interim years it has grown in both prestige and scope. It has been officially recognized by World Para Athletics, and each year some 250 or more wheelchair athletes from around the globe come to Oita to participate. The marathon is an important event for the people of Oita—not only was it founded by Dr. Yutaka Nakamura, a Beppu native (more on him in a moment), but local volunteers of all ages rally around the event to pitch in.

Ironman

For an inside look at the life of a wheelchair athlete, and the potential challenges they face while traveling Japan, we were joined by Pieter du Preez and his family. Born in South Africa, Pieter is a world-class athlete with an indomitable drive, a true embodiment of the spirit of competition. Although he participated in triathlons from a young age, his life changed forever when he was hit by a car while cycling in 2003, and broke his neck. While he was initially unable to move at all, he eventually regained a limited range of mobility—as a C6 quadriplegic, he can move his wrists, biceps and shoulders, but can't move his fingers or hands, and is paralyzed from the neck down.

He met his wife, Illse—an occupational therapist familiar with injuries like Pieter's—shortly after the accident, and they've been on the go together ever since. Not only has he completed TWO Ironman competitions, but he also holds the course record in Oita for the T51 Men Class (and managed another victory this year), and participated in the Paralympics in London in 2012. He travels throughout the year to compete in international competitions and to speak at events alongside his wife. They juggle it all with the responsibilities of day jobs and raising a child. Their story is inspiring—in no small part because of the practically unending positivity they seem to radiate as a family—and I'll admit I was a bit awestruck by Pieter's accolades. But I was also excited to explore the area with someone so down-to-earth, and to hear his insights into accessibility in Oita, and Japan as a whole.

Japan Sun Industries

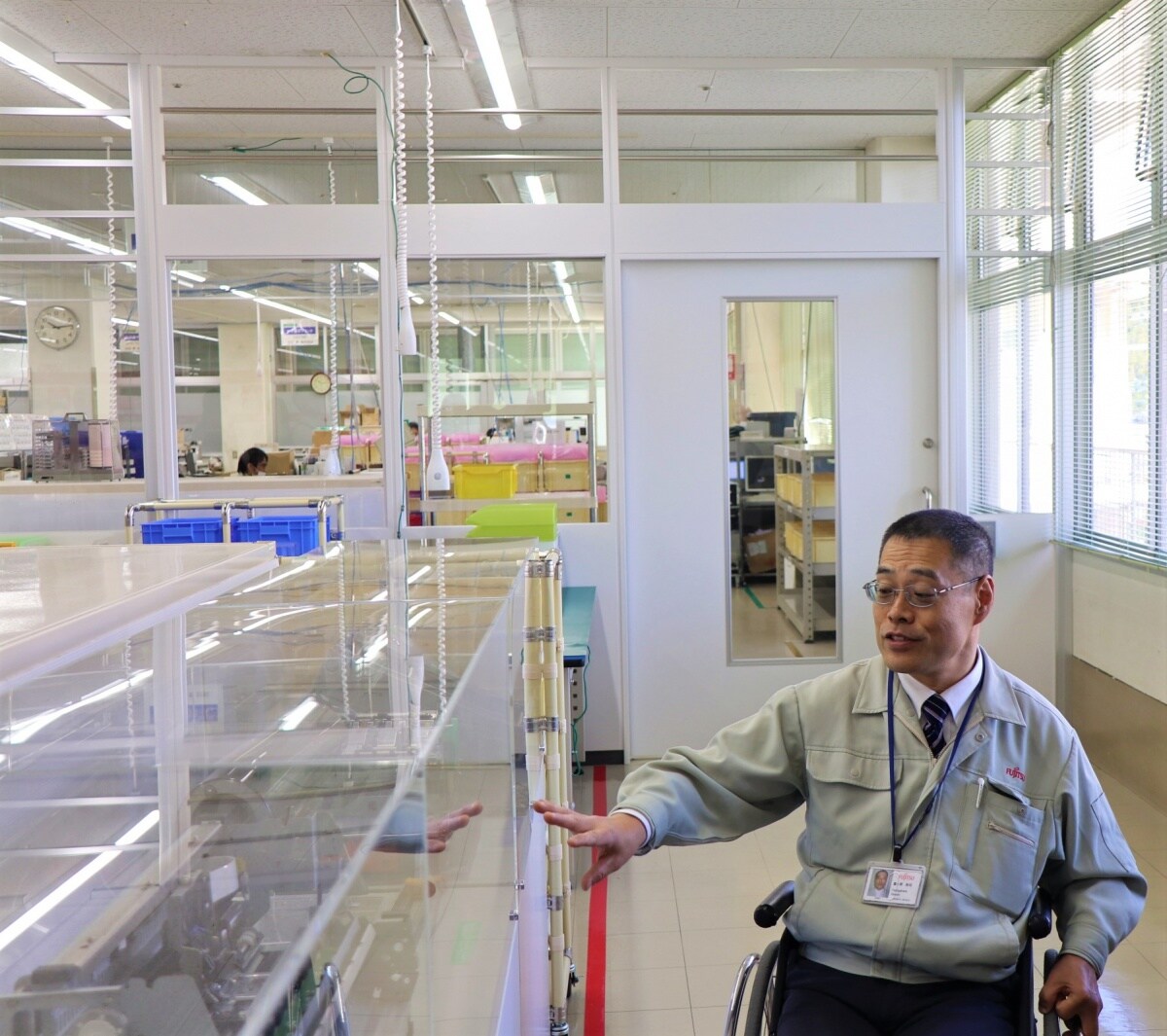

Our first stop was in Beppu, at Taiyo-no-Ie (太陽の家), or Japan Sun Industries as its known in English. From the outside, Japan Sun Industries seems like any other office headquarters in Japan; employees hard at work in a variety of fields, from electronics assembly and equipment repair to data processing and IT work. Some of the divisions are the result of joint ventures with high-profile Japanese companies like Fujitsu, Honda and Sony. So what makes Japan Sun Industries exceptional? A significant percentage of their employees are people with disabilities. Once you realize that, it becomes apparent just how much thoughtfulness went into JSI's conception and construction.

Like the Oita International Wheelchair Marathon, Japan Sun Industries was created by Dr. Yutaka Nakamura, dean of the Orthopedic Department of Beppu National Hospital. Dr. Nakamura was an advocate for people with disabilities who worked hard to improve both their quality of life and their place in society. Inspired by time he spent studying the techniques of Sir Ludwig Guttmann, which combined rehabilitation and sports to enhance the recovery of patients with spinal cord injuries, Dr. Nakamura established the Oita Prefecture Physically Disabled Sports Association, which held its own games in 1961.

He was also an outspoken proponent of including the Paralympic Games in the 1964 Tokyo Olympics—in the end, 375 athletes participated from 21 different countries. While the event was an undeniable success, the conditions in which the Japanese Paralympians lived paled in comparison to that of competitors from abroad, so Dr. Nakamura left the games with mixed feelings and a mission: to establish a facility to help people with disabilities achieve independence and integrate into a community to which they could meaningfully contribute. Thus, Japan Sun Industries was born under the motto "No Charity, but a Chance!"

Of course, the office buildings are equipped with ramps and elevators, as well as wide sliding doors and bathrooms for people with disabilities. Where most Japanese offices have carpeted floors, JSI does not, so that employees or visitors who use wheelchairs can move with ease. Similarly, where most offices ground electrical wires in the floor, JSI uses specialized cords that ground into the ceiling—one of many small but essential touches to ensure a safe and efficient working environment. And that's just the tip of the iceberg.

JSI is more than just a workspace; it's a barrier-free community. In addition to accessible housing, there's a local bank and a nearby grocery store, which has wonderfully large aisles (especially compared to the cramped corridors of supermarkets in Tokyo) and hydraulic checkout counters that can change elevation to match the needs of customers. Since JSI has such close ties to the marathon and other sporting events, there's a gym and training center with equipment suitable for people with different types of disabilities, as well as a basketball court and more, all of which is also open to the public for a small fee (a far cry from the typically expensive gyms in Japan). After working up a sweat, residents and locals can visit the on-campus hot spring for a nice soak, and then head to the community hall, which hosts different events throughout the year. The facility is 26,000 square meters (about 280,000 square feet), and though it's only a few minutes from the nearby Kamegawa Station, there are also wheelchair-accessible buses to help residents get around.

Yutaka Nakamura's son, and former president of JSI, Taro Nakamura is just as committed to improving conditions for people with disabilities as his father was. He hopes to share the culture created at JSI with the rest of the country.

To Hell & Back

https://pixta.jp

No trip to Oita would be complete without soaking it up in one of Beppu's gorgeous and abundant onsen. Of the 11 types of hot springs around the globe, 10 can be found in Beppu alone! The mineral qualities of the water varies from spring to spring, but the most eye-catching are the seven uniquely colored baths known as "the Hells." While the Hells aren't actually open to the public for bathing, there are so many other baths in the area that visitors are positively spoiled for choice.

I traveled with Pieter and his family in a shuttle bus equipped with a lift for people who use wheelchairs. In addition to the license required to drive buses on the narrow streets often found in Japan, the driver was also trained to assist wheelchair users in embarking and disembarking from the shuttle, and belting the wheelchair safely in place once aboard. Since Beppu is known throughout Japan as a hot spring resort town, many of the facilities have large parking lots that can accommodate tour buses, or shuttles for those with special needs, which makes shuttles equipped for wheelchair users a great way to get around.

We had the chance to stop by Hyotan Onsen, an incredible facility that boasts three Michelin stars—and just so happens to be the only hot spring in the country to do so! Hyotan Onsen has eight baths each for both men and women—including my personal favorite, outdoor baths—as well as a unique mixed-gender sand bath (which is exactly what it sounds like!). In addition to the wide variety of baths available, Hyotan also offers traditional cooked meals that are made in pots using steam from the springs!

But the highlight for Pieter was the family baths, which are private onsen that can be reserved for some family fun! Not only are there are 14 beautiful baths—half are barrier free!—from which to choose (the water of which is changed for each reservation), but those who are unaccustomed to bathing culture or a little shy can enjoy soaking in bathing suits (as opposed to in the nude). Since you can soak in privacy and at your own pace, it was the perfect way for Pieter and his family to experience a Japanese hot spring for the first time!

If you're too busy soaking in the sights to budget time to soak in a hot spring, you can still take a break at one of the many footbaths in the area. On top of being a great place to rest when your dogs are barking, they're completely free, which means the price is right! The natural spring water is exactly what you need to put some pep in your step while touring—just be sure to bring a small towel for your feet, unless you want to drip dry.

For some truly unbelievable scenery, be sure to stop by the Yukemuri Observatory (literally "Onsen Steam Observatory"). There's something almost magical about seeing steam rising on a hillside throughout an entire city. While there's no wrong time to go, it looks the most romantic at sundown in seasons when the weather is a little cooler, since the steam really hangs in the air.

Along the Shore

Our final destination with Pieter was Tanoura Beach. Just 15 minutes from Oita Station, Tanoura Beach is free to access, and a great place for some fun in the sun from July to August. There's an incredible pirate ship playground on the shore (which even I, in my 30s, was very tempted to climb aboard), as well as a rest house, a dining area and a scenic little island to stroll around.

Plus, like many other places in Oita, the view was incredible. But what was really interesting about the area was the paved paths that run parallel to the shore, which were perfect for jogging, but also an ideal picturesque training environment for wheelchair athletes. Pieter was quick to mention how he'd love to go through his paces in such lovely scenery, and no sooner were the words out of his mouth than we spotted some other wheelchair athletes training for the marathon.

Like any group of professionals or enthusiasts who happen to cross paths, they immediately started talking shop—where they were from, what division they would be competing in, where they've raced before. Although Pieter used an interpreter, the considerate culture Oita has cultivated in regards to people with disabilities played a key role in breaking down the language barrier, and the spirit of supportive competition surrounding the athletes could be understood saying anything at all.

Amazing day in Beppu, Japan#jnto pic.twitter.com/IkRnoPnVPv

— Pieter du Preez (@supapiet) November 15, 2018

If it wasn't obvious from the photos (and the fact that he literally spells it out in his Tweet), Pieter and his family had a great time exploring Oita. Although it was time to say goodbye, there was still more to discover in Oita!

A Local View

For the rest of the journey, I accompanied a local wheelchair user from Oita, in part to better understand how the area met his own daily needs as a resident. Instead of a family-sized shuttle bus, we traveled in a van equipped with a lift for wheelchair accessibility. Our first stop required a short drive into the mountains of Beppu.

Global Education, Personal Consideration

Ritsumeikan University is one of the most prestigious private institutions of higher learning in Japan. While the original campus is in Kyoto, Beppu is home to Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University, a satellite school founded in the year 2000 on the principles of international mutual understanding, peace and humanity.

Asia Pacific University, or APU as it's known by students, faculty and locals, is unlike any other I've visited in Japan. It has a small but open campus overlooking the rest of the city, with modern facilities equipped with ramps, automatic doors and elevators—we were given an orientation by currently enrolled students (in both English and Japanese), and my travel companion was able to navigate the tour with ease.

Even though it was a rainy morning (the weather changes quickly high up in the mountains, next to the sea), I couldn't help but notice that APU buzzed with a special kind of energy. It wasn't just that students were shuffling in and out of buildings on their way to or from classes, stopping to chat with friends or line up for a bite to eat at some of the food carts in the campus square—to be frank, it was the sheer diversity of the student body. According to the enrollment stats at APU, 50% of the student body (nearly 6,000 undergraduates and graduates in total) are international students. This is remarkable when considering how, in general, Japan is a fairly homogenous society where ethnic Japanese make up over 98% of the population.

Classes at APU are taught in Japanese or English, and students are eligible for enrollment as long as they can prove their proficiency in either language. International students are given an incredible amount of support over their first year, in the form of intensive language and culture classes to help them navigate Japan, resources to help get used to the ins and outs of daily life, as well as scholarships that can cover up to 100% of tuition depending on financial need. While that's fantastic, the cultural exchange and education goes both ways. There are tons of multicultural events on campus throughout the year, an incredible variety of dining options from countries all over the globe (including vegetarian, vegan and halal dining options), student organizations and study materials focused on language learning and more!

When it comes to accessibility, APU fires on all cylinders. The campus is a melting pot of students from different backgrounds with all kinds of different needs, and the environment created by the university has had a clear, positive effect on the rest of the city. I was extremely impressed by what I saw, and it had me itching to go back to school!

A Station by Any Other Name

Our next stop was JR Kamegawa Station, which I mentioned previously in regards to its close proximity to Japan Sun Industries. Inside I encountered the station master, a commanding, extremely photogenic turtle (which are called kame in Japanese).

While it should come as no surprise, considering its location, Kamegawa Station had a lot of simple adjustments that have greatly improved its accessibility. Take the turnstyle, for example. Most JR stations have ticket gates or manned ticket offices that are accessible to people with disabilities, but Kamegawa takes it even further. The IC card reader was vertically aligned at the front of the gate, instead of horizontally, and a front-facing station to recharge the IC cards was right next to it, instead of in a counter away from the turnstile as they are typically.

The support extends to the ride itself, as well. JR attendants were ready on the boarding platform to ensure safe and smooth passage to and from the train, and there was designated seating for wheelchair users and people with other disabilities. Our final destination was Oita Station, the largest in the prefecture, and even though the train and platforms were quite busy, my traveling companion was able to navigate the station without missing a beat.

Oita Station itself was quite beautiful. It's modern and clean, and there were a lot of artistic and playful touches—my favorite was the bathrooms, which were decked out to look like the curtained entries to a hot spring. As we were leaving the station, we happened to cross paths with some newly arrived participants in the Oita International Wheelchair Marathon, who were being escorted to the nearby hotel by local volunteers.

Art Enables

https://pixta.jp

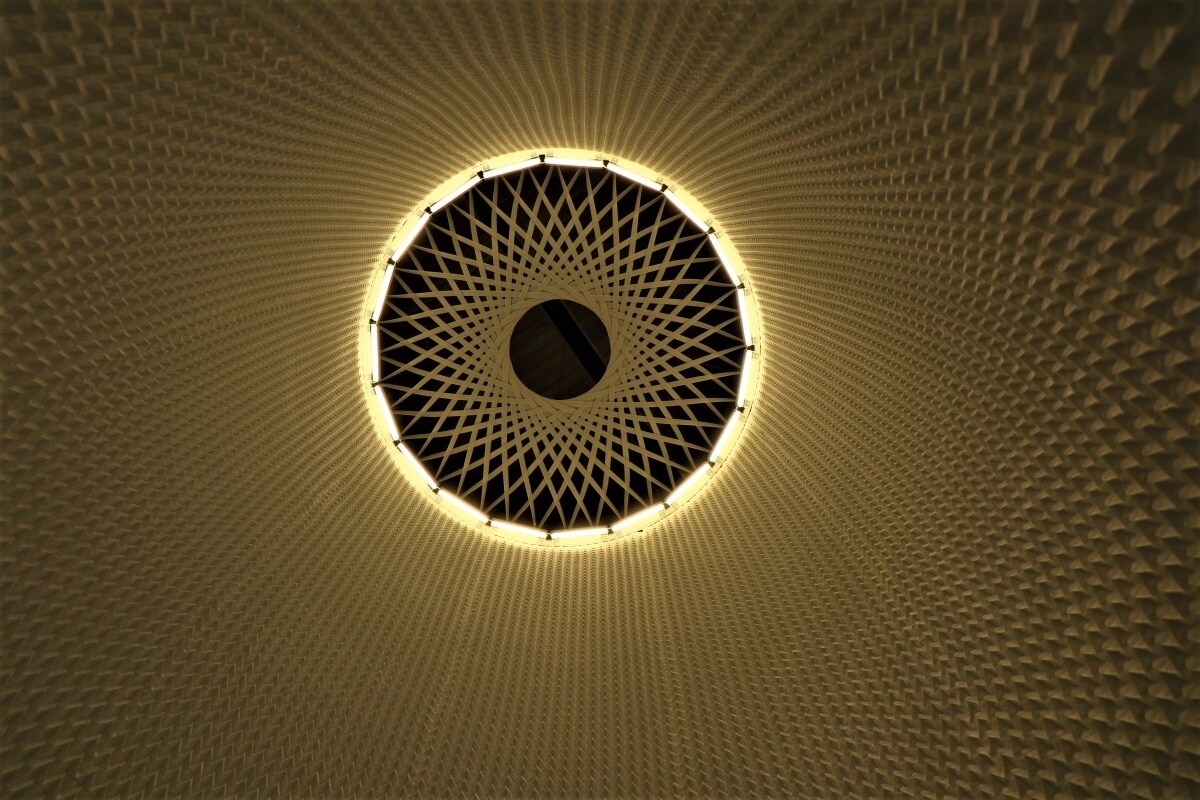

The city of Oita is home to the Oita Prefectural Art Museum, which was designed by Shigeru Ban, a modern architect and artist who is best known for his development of cost-effective temporary housing made out of paper to help with disaster relief, and winner of the Pritzker Architecture Prize. The glass facade of the museum is beautiful, and parts of it can be opened for different types of exhibitions in fair weather.

The building itself, and many pieces of art inside, incorporate the use of wood and geometry to dazzling effect. OPAM is said to be a museum "of the five senses," a place for play, and many of the works engage visitors on more than just a visual level.

OPAM also facilitates the same type of accessibility that I had come to expect from Oita at this point, which doesn't make it any less impressive. The museum connects to the station via elevated tunnel for use when the weather is bad, and the main entrance had a ramp for wheelchair users. Although the building is three stories, each floor had an elevator (as well as escalators), and the bathrooms were all equipped for use by people with disabilities.

While OPAM was beautiful as a whole, the highlight was an exhibit in their temporary gallery, a huge collection of works by literally hundreds of local artists with physical and intellectual disabilities. It was incredible to see the creativity of so many different individuals, and was especially moving to witness firsthand how young children with disabilities reacted to the work of their older peers.

The entire gallery was an uplifting reminder that creativity is a force without limitations, capable of overcoming any obstacle or barrier.

Power Spots

Our final destination was Usa Jingu, a Shinto shrine in the city of Usa in the northern part of Oita Prefecture. Usa Jingu has a history that dates back to the eighth century, and is the earliest place to enshrine the deified Emperor Ojin. Beyond its history, Usa Jingu is also considered one of Japan's most incredible Power Spots, which are places throughout the country at which visitors can recharge their physical, mental or spiritual batteries, so to speak. Usa Jingu is incredibly peaceful, surrounded by lush forests, but the typical entryways can be quite difficult for people with disabilities to navigate.

Fortunately, Usa Jingu has a tram in place, so wheelchair users and people with other physical disabilities can still visit this incredible site. Although the the small tram is located on the back side of the shrine, it's large enough to fit several people, and is technically free to use (though shrine administrators humbly request a donation of ¥100). Simply press the call button at the base of the back side of Usa Jingu, and follow the ramp up to the main hall (which is considered a National Treasure).

It was my first visit to Usa Jingu, and—perhaps more surprising, considering he's a local—my traveling companion's as well. Although he was from the area, even he didn't know about the tram, and was pleasantly surprised at the opportunity to visit. As is tradition, he wasted no time in making an offering to the gods.

Oita Prefecture is more than ahead of the curve when it comes to the concepts of barrier-free or universal tourism. Based on what I saw—and the reactions of the people with whom I traveled—it's setting the bar for the rest of the country. If preparations for the 2020 Olympic & Paralympic Games are based around the same compassionate principles and thoughtful implementation found throughout Oita, then Japan is well on its way to creating a truly barrier-free environment.

Editor's Note

This article was written in cooperation with the Japan National Tourism Organization and the Tokyo Organizing Committee of the Olympic & Paralympic Games.