History of Same-Sex Samurai Love in Edo Japan

While the LGBT+ community might not meet widespread acceptance in contemporary Japan, it seems that things used to be somewhat different in the Edo Period.

By Diletta FabianiPacification, Prostitutes & Kabuki

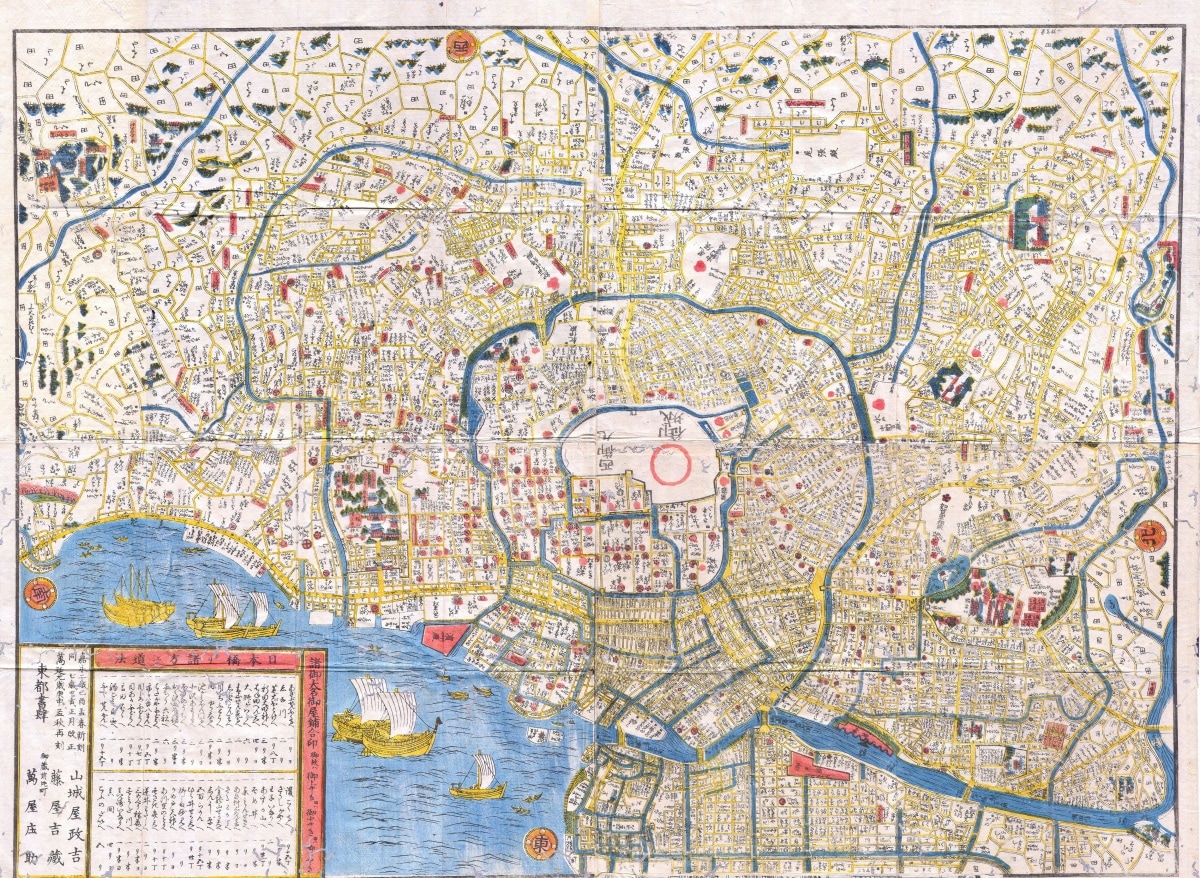

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1849_Edo_Period_Japanese_Woodcut_Map_of_Edo_or_Tokyo_Japan_-_Geographicus_-_Edo-japan-1849.jpg

When Japan started to become more peaceful, two phenomena occurred at the same time. On one hand, urbanization and lack of war brought more and more people to the cities; on the other hand, the samurai class lost power and wealth in favor of the middle class and merchants. Both phenomena are important to understanding why the wakashudo in the samurai class came to an end and started to flourish in kabuki theaters.

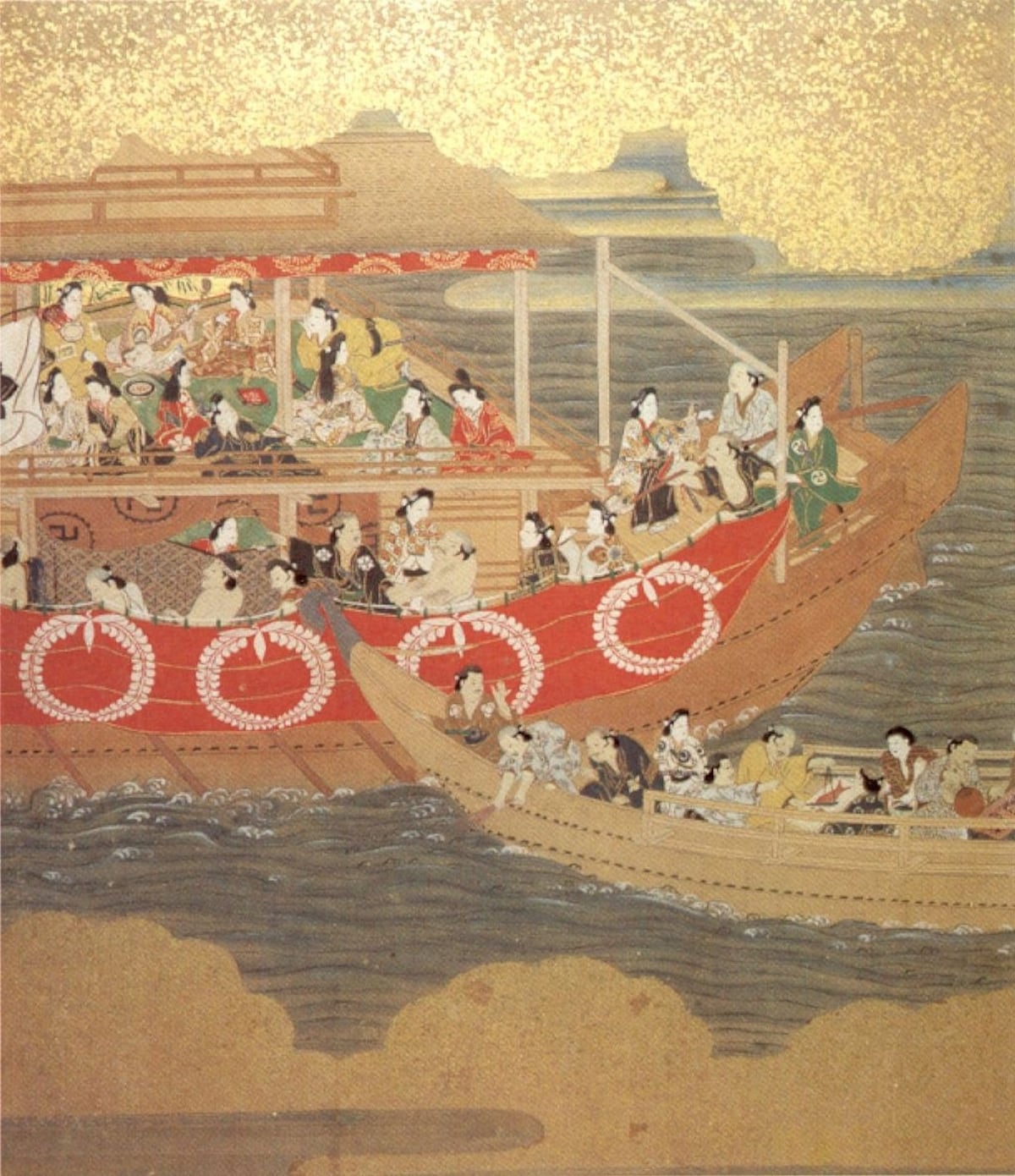

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%27Scenes_of_Common_Pleasure%27,_detail_of_one_panel_from_a_pair_of_six-fold_screens,_ink,_color_and_gold_accents_on_paper,_third_quarter_of_17th_century_Japan,_Honolulu_Academy_of_Arts.jpg

First, we have to consider how this urbanization happened. Once the samurai were gathered in castle cities, need for all kinds of infrastructure and goods came with them: this meant that peasants would also come to the cities to find jobs. It's not new in history for customs of the elite to be adopted by the lower classes; and, with time, merchants became richer and richer, so why not spend their money emulating the tastes of the socially superior elite—including wakashudo. And for those who could not afford a full-time apprentice or servant, prostitutes became an easy solution to loneliness and desire. Once again the men-to-female ratio would be eschewed in favor of men.

Additionally, as we have seen above, the decline in wealth of the samurai class meant not only that young people would not go into a samurai career, but also that samurai had less and less wealth on their hands to continuously support eventual younger disciples. Thus prostitution became an easy and widespread solution for those walking the wakashudo.

What's the Connection to Kabuki?

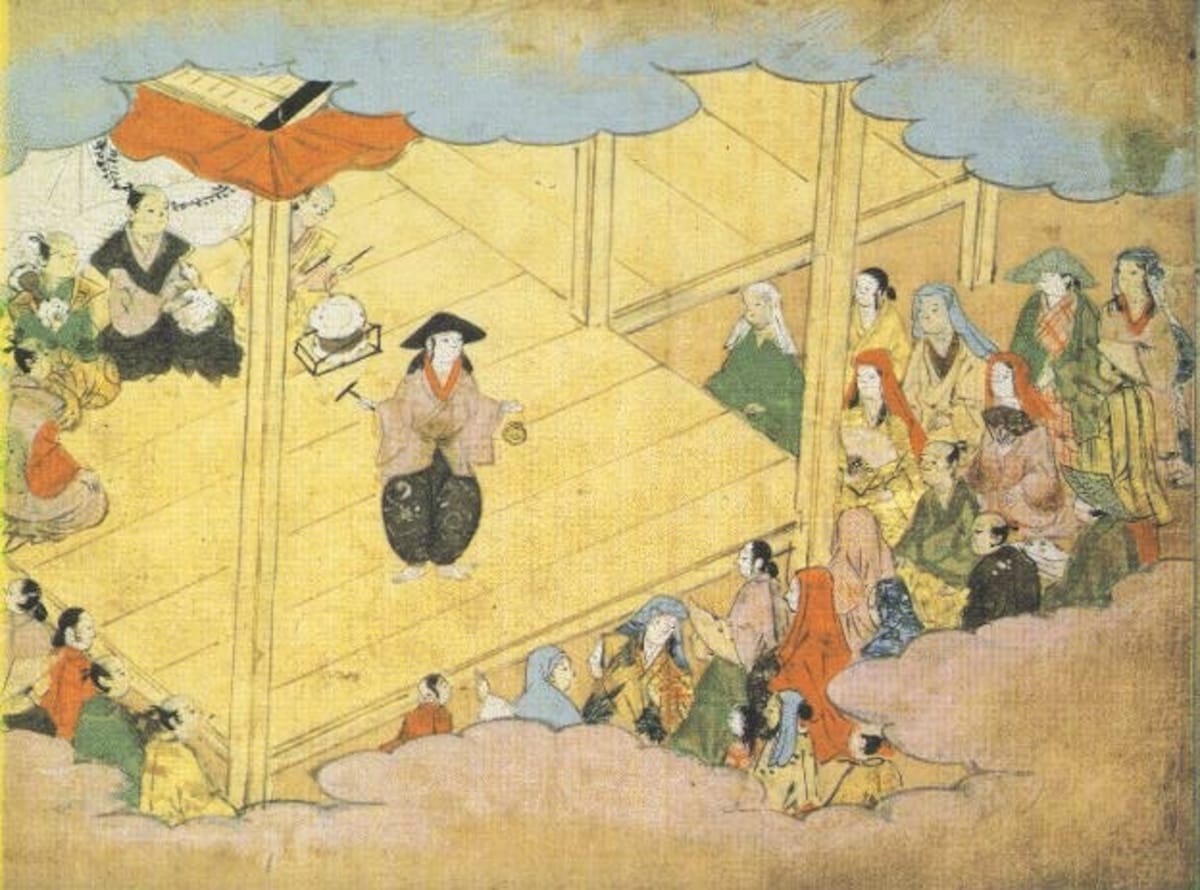

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Izumo_no_Okuni.jpg

In the beginning, kabuki plays would also see the presence of women on stage. Actually, the creator of kabuki was a woman, Izumo no Okuni, who started performing in a unique style that mixed dance, drama and intriguing stories. However, female kabuki was banned in 1629 on the grounds of being “too erotic;” from then on, all parts were covered by men. Wakashu (young boy) actors took the place of women, drawing themes from wakashudo stories. But, due to the increasing problem of these young performers also practising prostitution on the side, a partial ban was also issued on wakashu-kabuki—with a caveat that female and male roles would need to be clearly separated, and actors could only perform as one of the two sexes in one season. Naturally, female roles were taken over by young males because of their less masculine appearance and higher-pitched voice.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Odori_Keiy%C5%8D_Edo-e_no_sakae_by_Toyokuni_III.jpg

So kabuki theater became the perfect place to look for young, beautiful men, who soon became the object of desire of men and women alike. From there on, the government tried several times to make kabuki more “manly” and less lascivious by imposing various rules on appearances and roles, with meager results. Thus, it was common for famous kabuki actors in this period to have patrons and lovers of both sexes, with the stage being the perfect place to show off their talents, beauty and the irresistible mix of androgynous looks and manly character.

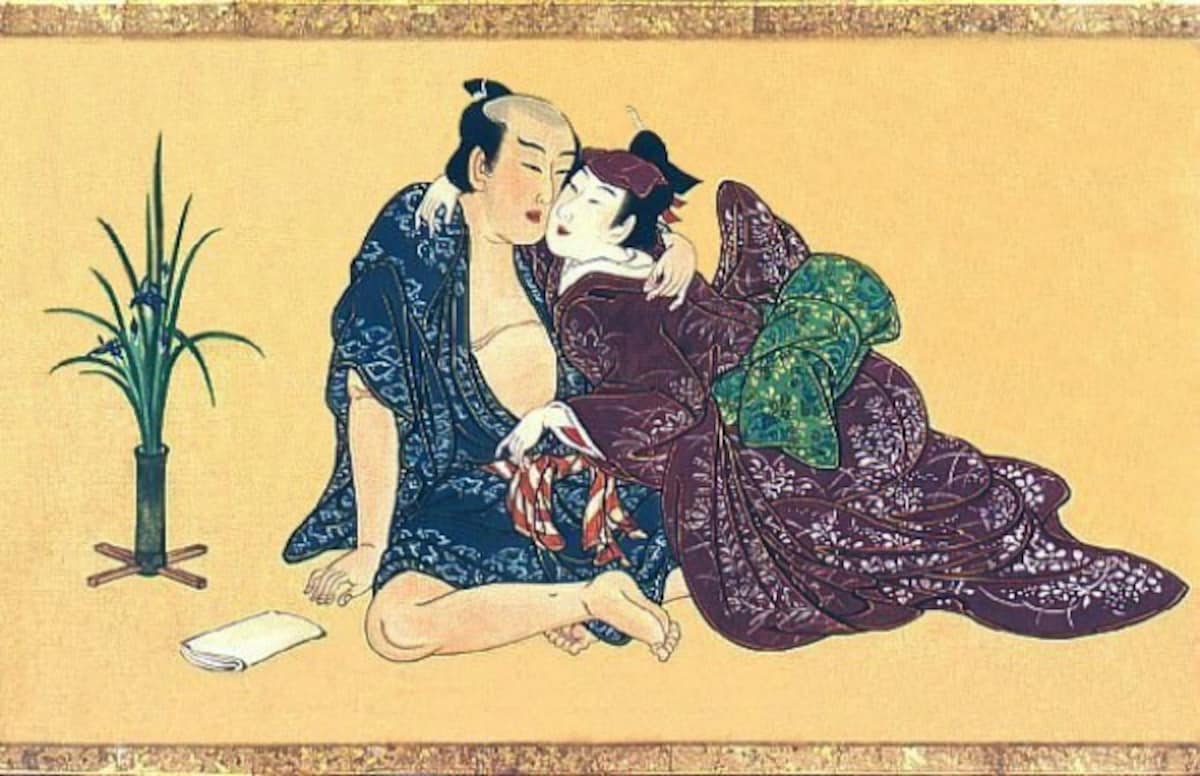

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Miyagawa_Issho_hand_scroll.jpg

Less talented kabuki actors could still resort to prostitution to make ends meet, as they would be in high demand among both men and women alike. Kagema (陰間) became a common term to indicate male prostitutes who were passed off as kabuki apprentices. Often they were sold as indentured servants at a young age to brothels or theaters. They became extremely popular among the merchant class in the Edo Period, and the popularity of prostitution was one of the reasons why the “golden age of homosexuality" in Japan eventually came to an end.

https://pixabay.com/photo-58060/

With the start of the Meiji Era, the government began cracking down on prostitution. In addition, Western morals and ways of life were imported to Japan, and the Western definition of homosexuality was not welcome in this new cultural environment. Homosexuality was once again relegated to the shadows of sins, leaving behind a plethora of artwork in literary and visual form.

If you want to know more about this topic, the following titles might be of interest. Don’t forget to let us know your personal recommendations below.

Gary Leupp, Male Colors - The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan

Gregory M. Pflugfelder, Cartographies of Desire: Male–Male Sexuality in Japanese Discourse, 1600–1950

Joshua S. Mostow, "The Gender of Wakashu and the Grammar of Desire", in Joshua S. Mostow; Norman Bryson; Maribeth Graybill, Gender and Power in the Japanese Visual Field

Louis Crompton, Homosexuality and Civilization

Dharmachari Janavira, Homosexuality in the Japanese Buddhist Tradition

Sara K. Birk “Sex, Androgyny, Prostitution and the Development of Onnagata Roles in Kabuki Theatre”, MA Thesis