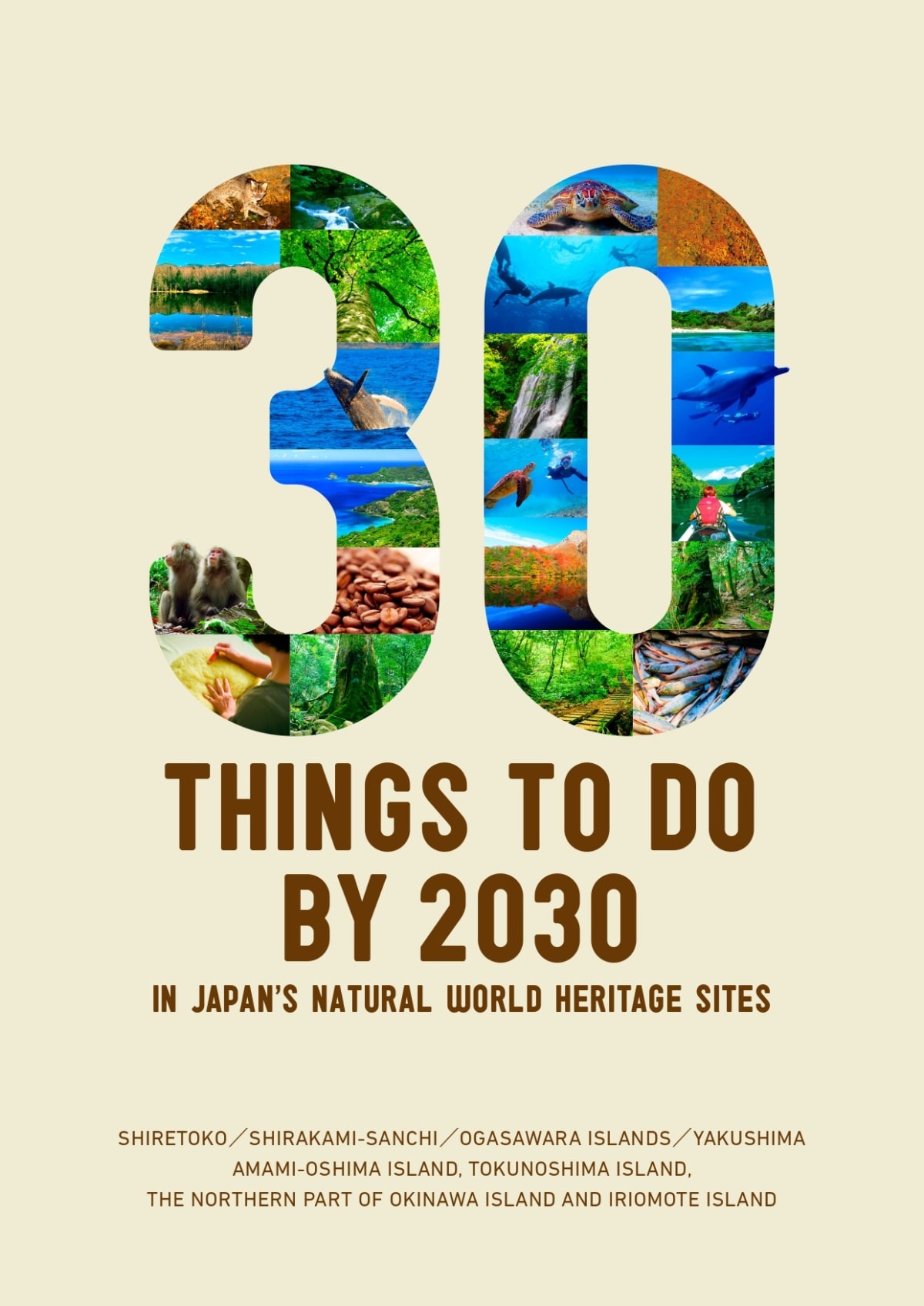

Why You Must Go to Japan’s 5 Natural Heritage Sites

As Japan reopens to travelers following the coronavirus pandemic, now is the perfect time to explore its unique ecotourism attractions. From white sand beaches to volcanic hot springs, Japan abounds with natural wonders. Five of these places are special enough to be on UNESCO’s World Heritage List, and make for unique travel destinations.

By AAJ Editorial Team

Japan’s five World Natural Heritage properties are must-see destinations for truly memorable travels centered on nature and conservation. Witness the spectacle of sea eagles flying over the drift ice. Take a “forest bathing” dip in the old-growth beech forests or climb a mountain to one of the world’s oldest trees. Swim with dolphins and sea turtles or take in unforgettable views on a coastal cleanup expedition. For tips on how to enjoy these and other top nature experiences in Japan, check out the informative digital brochure “30 Things to Do by 2030 in Japan's Natural World Heritage Sites” here: https://world-natural-heritage.jp/en/digitalbrochure/

Shiretoko

© Rausu Town Hall

This rugged, 70-kilometer-long peninsula extends from Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost main island, into the Sea of Okhotsk. The name Shiretoko is derived from a native Ainu term meaning the end of the Earth. It’s indeed a land of extremes: 1,500-meter-tall active volcanoes and drift ice stretching out for kilometers from the shore. The Sea of Okhotsk ice is the result of geography as warm currents from the south are blocked by the Japanese archipelago, causing freshwater from the Amur River to freeze in winter. In 2005, the peninsula was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List due to the fact that it is the southernmost point where sea ice routinely forms in the Northern Hemisphere.

Shiretoko is also a place of breathtaking beauty and natural diversity. Aside from the jagged ice floes, visitors can see majestic waterfalls, towering mountain peaks and verdant forests. The star attraction here is the Ussuri brown bear, which can reach more than 2 meters in height. Too dangerous to approach on land, Ussuri brown bears often can be observed from cruise boats as they hunt along the shores of the peninsula. Other wildlife here includes the endangered Blakiston’s fish owl, killer whales, Ezo sika deer, Ezo red fox and the Hokkaido squirrel.

Shirakami-Sanchi

©Isao Yonezawa

In the northern part of Honshu, Shirakami-Sanchi mountain range is home to one of the largest remaining virgin beech forests in East Asia. As one of the first natural sites in Japan to be inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, this wilderness is a unique remnant of a much larger woodland. The 17,000-hectare registered area is part of the much larger 130,000-hectare Shirakami-Sanchi mountain range extending from Aomori to Akita prefectures.

The area receives heavy snowfall in winter due to moisture over the Sea of Japan. Siebold’s beech, a tall, deciduous tree that can grow from sea level to altitudes up to 1,000 meters, thrives in this harsh environment. These trees once covered northern Japan but most were felled and replaced with artificial cedar plantations. The beech forest is also home to the Asian black bear and the Japanese serow, an antelope-like mammal, as well as 94 species of birds including the endangered golden eagle and black woodpecker. One of the travel highlights here is an autumn hike through golden beech forests unchanged since they developed some 8,000 years ago.

Ogasawara Islands

©Ogasawara Village Tourism Bureau

After arriving in the Ogasawara Islands, you won’t believe you’re still in Tokyo. This island group in the Pacific Ocean is about 1,000 kilometers south of central Tokyo yet is still part of Japan’s capital. The islands have a long history of colonization, including settlements by British, American and Japanese colonists, but remain a unique, sparsely populated environment due to their natural wonders and their isolation; they are basically only accessible by a 24-hour ferry ride from Tokyo.

The archipelago consists of more than 30 tropical and subtropical islands characterized by lush vegetation, sandy beaches and crystal blue waters. Only two islands, Chichijima and Hahajima, or Father Island and Mother Island, respectively, are inhabited. Sometimes referred to as the “laboratory of evolution,” the Ogasawaras evolved their own distinctive ecosystem and species, and the chain was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list in 2011. Aside from the Bonin petrel and Bonin flying fox, you can see green sea turtles, dolphins, and, between February and April, humpback whales. For ecotourism lovers, the Ogasawaras are a paradise for swimming, diving, snorkeling, sea kayaking, hiking and sailing. Guided tours bring visitors to exquisite spots such as Minamijima, an uninhabited island where turquoise waters pour through a natural limestone tunnel to form a picture-postcard lagoon ringed by white sand.

Yakushima

©Yakushima Recreation and Forest Conservation Management Committee

Just 60 kilometers south of the Kyushu mainland, Yakushima stands apart from the rest of Japan for its towering and ancient cedar trees, known as yakusugi. The mountainous interior of the island is home to some of the world’s oldest trees, and hiking up to them is an unforgettable experience. Yokushima’s forests are a surreal universe of emerald-colored moss, thick roots webbing over great glistening rocks, all shot through with torrents gushing from the mountain. It seems more a science fiction film set than an island in the Pacific.

Found above 500 meters, some of Yakushima’s cedars have grown to over 20 meters tall and 8 meters around, and are thousands of years old. The goal of many hikers exploring the island’s interior, the Jomon Sugi cedar tree is a staggering 16 meters in circumference and more than 25 meters high. Estimates of its age range from 2,170 to 7,200 years, but everyone agrees it’s the largest and oldest specimen of Cryptomeria japonica. After burning calories on a hike, Yakushima has several hot springs to soothe your tired muscles. The island is also home to unique animals such as the Yakushika deer and Yakushimazaru, a subspecies of the Japanese macaque.

Amami-Oshima Island, Tokunoshima Island, Northern part of Okinawa Island, and Iriomote Island

© Oceanz

The UNESCO World Heritage listing for this group of four islands in the Ryukyu archipelago consists of 42,698 hectares of subtropical rainforest that is completely uninhabited. Reflecting the volcanic chain’s distinct natural evolution after it separated from the Eurasian continent, the islands abound with endemic species including the threatened Lidth’s jay, Amami rabbit and Ryukyu Long-haired Rat. Each island along the chain has its own unique attractions, offering numerous ecotourism experiences.

The Kinsakubaru Forest on Amami-Oshima Island is a primeval woodland where evergreen oak, chinquapin and Chinese guger trees grow more than 10 meters tall. South of Amami-Oshima, Tokunoshima is the natural habitat of the Amami rabbit, the Amami woodcock and many frog species; it’s also known for its unique tradition of bullfighting, in which bulls are trained to push opponents out of a ring like sumo wrestlers. In the northern part of Okinawa Island, the Yanbaru Forest is a lush subtropical jungle is perfect for kayaking, waterfall hikes and observing rare species such as the native Okinawa rail, aka the Yanbaru kuina, whose existence was only confirmed in recent decades. Remote Iriomote Island is the only known habitat of the Iriomote Cat, a critically endangered species inhabiting the subtropical forests. Iriomote is also renowned for its rich natural beauty, including long sandy beaches, refreshing jungle waterfalls and some of the oldest mangrove trees in Japan.