Daughters of Meiji: Women's Education in Japan

At the dawn of the Meiji Period, three young girls were sent to live in the United States to experience American education and society firsthand and bring their knowledge back to Japan. Author Janice Nimura discusses their cross-cultural journey and their influence on Japanese society.

By Highlighting Japan

When the Iwakura Mission set off for the United States and Europe in 1871, their goals were to gain recognition for the newly created Meiji government, renegotiate unequal treaties, and research industrial, political, military and educational systems across the Western world.

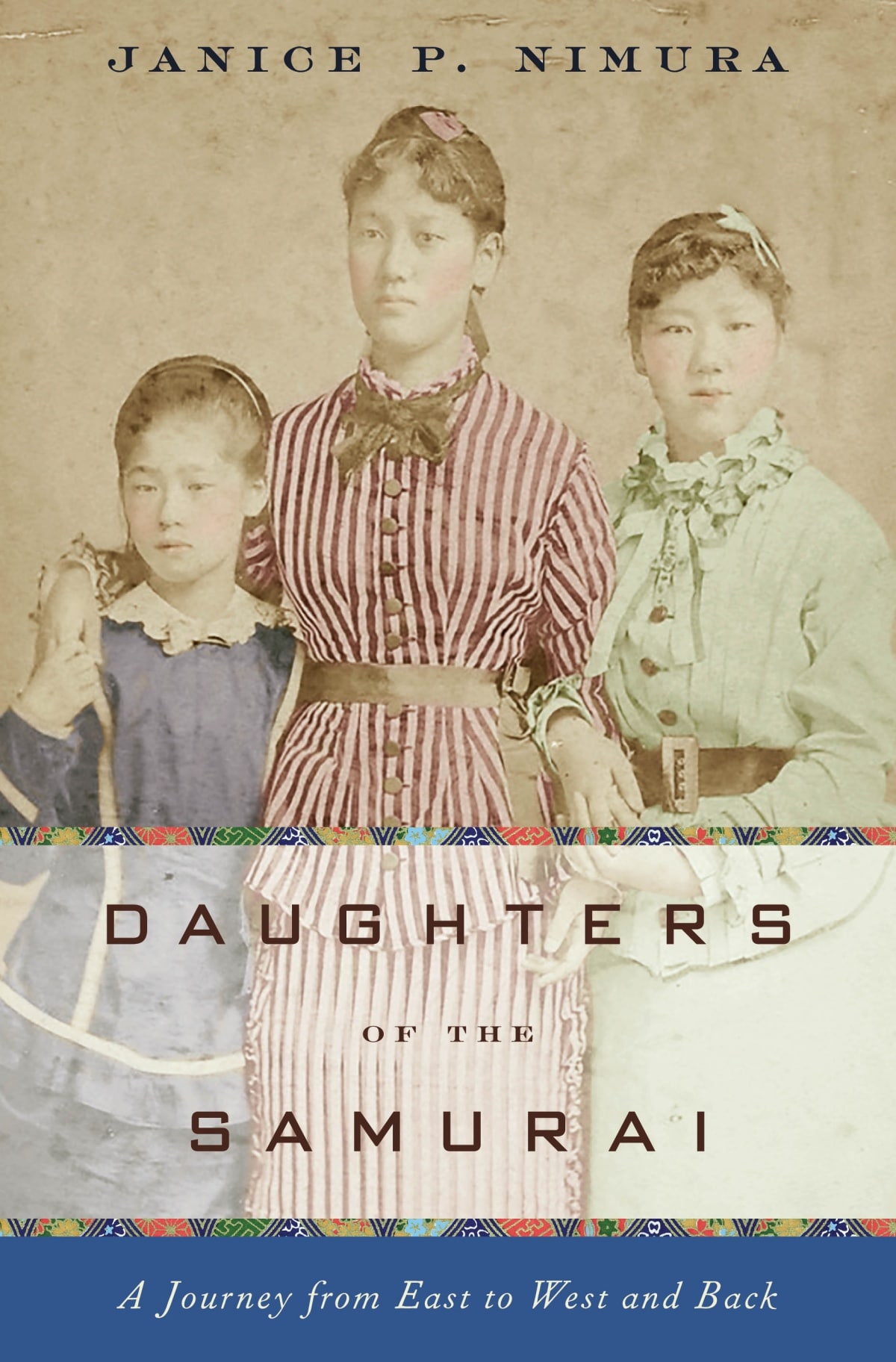

Three young girls were among the statesmen and students sent to find ways to modernize Japan. The empress of Japan set them the task to bring back the methods needed to jumpstart women’s education in Japan. The youngest, Umeko Tsuda, was just six years old at the time.

For Janice Nimura this episode encapsulates the topsy-turvy nature of the Meiji Period (1868-1912), noting that the effects of Eastern and Western cultural currents crashing together make it a fascinating period in Japanese history.

In her book Daughters of the Samurai: A Journey from East to West and Back, Nimura brings the women’s extraordinary cultural journey to life.

“It was a perfect lens for examining the Meiji Period and telling a story from the point of view of women, who are often overlooked in history,” she says. “You don’t need an interest in Japan to be drawn in by the story of these girls and their remarkable situation.”

Sent to a country for a decade where they couldn’t speak the language and charged with becoming educators seems almost unbelievable today, especially when considering that Tsuda was only six years old. However, despite her youth and the many hurdles she faced, her mission was a success: in 1891 she created a scholarship system for women to study in the United States, and in 1900 went on to found the English School for Women.

“They never questioned their mission or tried to shy away from their responsibilities,” Nimura notes, touching on Tsuda’s discipline and ability to handle a mission assigned at such a tender age.

“Tsuda believed in the importance of educating the next generation,” says Yuko Takahashi, the university’s president. “She had a broad, long-term outlook, and she was a driving force for education who excelled at getting things done. She was a real role model, using her international network to contribute to society.”

After briefly returning to Japan to teach at a women’s school, she eventually sailed back to attend Bryn Mawr College. The tenets of that institution, such as service to one’s community and leadership, provided the foundations for her own school, which still flourishes today as Tsuda University.

Takahashi also notes that thanks to Tsuda’s scholarship system, twenty-five women were able to study abroad. “One after the other, they became leaders in their fields, contributing to society as a whole.” This philosophy of giving back remains a core tenet of the school, which instills the importance of making a difference and lifelong learning on its students.

“We can all learn from their flexibility, ability to take tradition and use it in unexpected settings, and sheer discipline regarding education,” Nimura says. This grit, determination and samurai spirit allowed Tsuda to spearhead women’s schooling in Japan, and bring East and West closer together.