Bringing Japanese Performing Arts to Europe

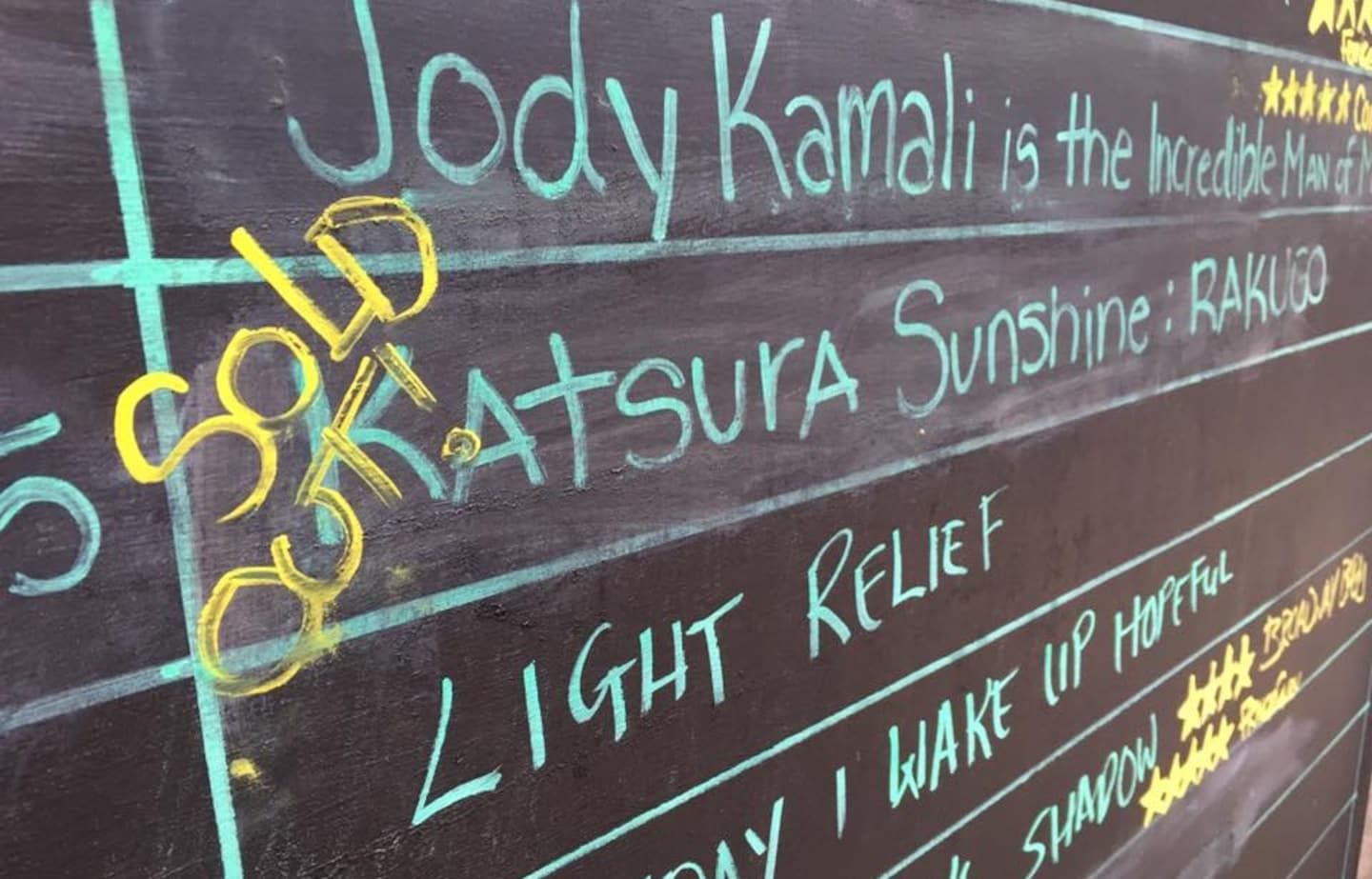

August 28 marked the end of my third year bringing Rakugo to the Edinburgh Fringe. This year I was fortunate to be in a fantastic venue called Sweet Venues, at the very central and popular Grass Market area of Edinburgh.

By Katsura Sunshinehttps://www.facebook.com/KatsuraSunshine/

I did 20 shows and the run was sold out, thanks to the great efforts of my friends in Edinburgh who helped spread the word.

I have written before that Rakugo is remarkable in its universality—it translates so well, which makes it a rarity for a humorous verbal performance art. Over the last five years I have performed in places as various as Singapore, Hong Kong, France, the U.K., Ghana, Senegal, Sri Lanka, etc., and have never found a place where I thought, "Hmm, Rakugo doesn’t work here."

I would attribute this to its simplicity. The first half of a Rakugo story, although the performer is kneeling on a cushion in a kimono, is much like stand-up comedy: Self-introduction, self-deprecating opening joke or two, observational comedy, a few words about the host city, town, group or company. Every storyteller creates his or her own material for this, and much is based on the performer’s own personality.

The second half is a one-person play where the Rakugo-ka differentiates characters by moving the head from left to right in conversation. There's almost no narration, so perhaps “story-performing” would be a more accurate way of describing it than ”story-telling.”

https://www.facebook.com/KatsuraSunshine/photos/pcb.1088021991279283/1088021431279339/?type=3&theater

A lot of Japanese friends and colleagues are surprised that Rakugo works in other countries, translated into other languages, because it is a traditional art form—its history reaches back 400 years, so a lot of Japanese culture is reflected in its stories, characters and situations.

But I've discovered that its roots in Edo Period (1603-1868) culture actually work it its favor when translating and performing abroad. So much humor in, for example, stand-up comedy, is predicated on common reference—so much so that for me as a Canadian I often don’t see the humor in a British comedian’s material, not because my sense of humor is different, but because I don’t get the cultural references. I didn’t grow up in the U.K., see the same TV shows as a kid, go through the same school system, etc. The same British comedian coming to Canada to perform will edit his or her material; comedians know what humor requires local knowledge and what's more universal.

But Rakugo comes from 400 years ago. And Rakugo performers have constantly adapted the stories so their immediate audiences can understand, and cultural references and archaic details are either explained or edited out. Japan 400 years ago was much different to the Japan of today, so Rakugo has already crossed the barriers of time and the cultural differences between Edo Period Japan and modern Japan. So it only makes sense that the stories are ready to cross the language barrier and national borders as well.

https://www.facebook.com/KatsuraSunshine/photos/pcb.1088021991279283/1088021851279297/?type=3&theater

If asked where my favorite place to perform Rakugo is, I would have to say the U.K.: London and Edinburgh. Not only do the audiences really “get it” and genuinely laugh a lot, but the comments I get after the show are very deeply considered and impressively observed. I think it's a country that has been and is still very much steeped in traditions of live performance.

This actually came as a surprise the first time I performed in London two years ago, because Rakugo is not exactly what you would call "dry British humor." It's very straightforward, simple humor, free of irony, sarcasm, or multiple levels of meaning. However, it makes sense when you think about it: British humor is different from Canadian humor is different from American humor. And yet people still appreciate different sensibilities in comedy from the one that's typical of their own country.

That's the beauty of Rakugo: So very, very Japanese, and yet, it seems, also so very universal.

Next up, London’s West End in September 2017!