How to Fix 7 Common Mistakes in Your Japanese

Here’s a list of seven Japanese nuances that foreigners frequently get wrong, as chosen by one of the reporters on RocketNews24's Japanese sister site. Keep in mind that these aren’t mistakes that would necessarily prevent you from being understood, but rather mistakes that, if you can fix them, will make you sound more like a native speaker.

By SoraNews244. Differentiating between 'iru' and 'aru'

http://en.rocketnews24.com/2015/12/12/seven-mistakes-foreigners-make-when-speaking-japanese-and-how-to-fix-them/

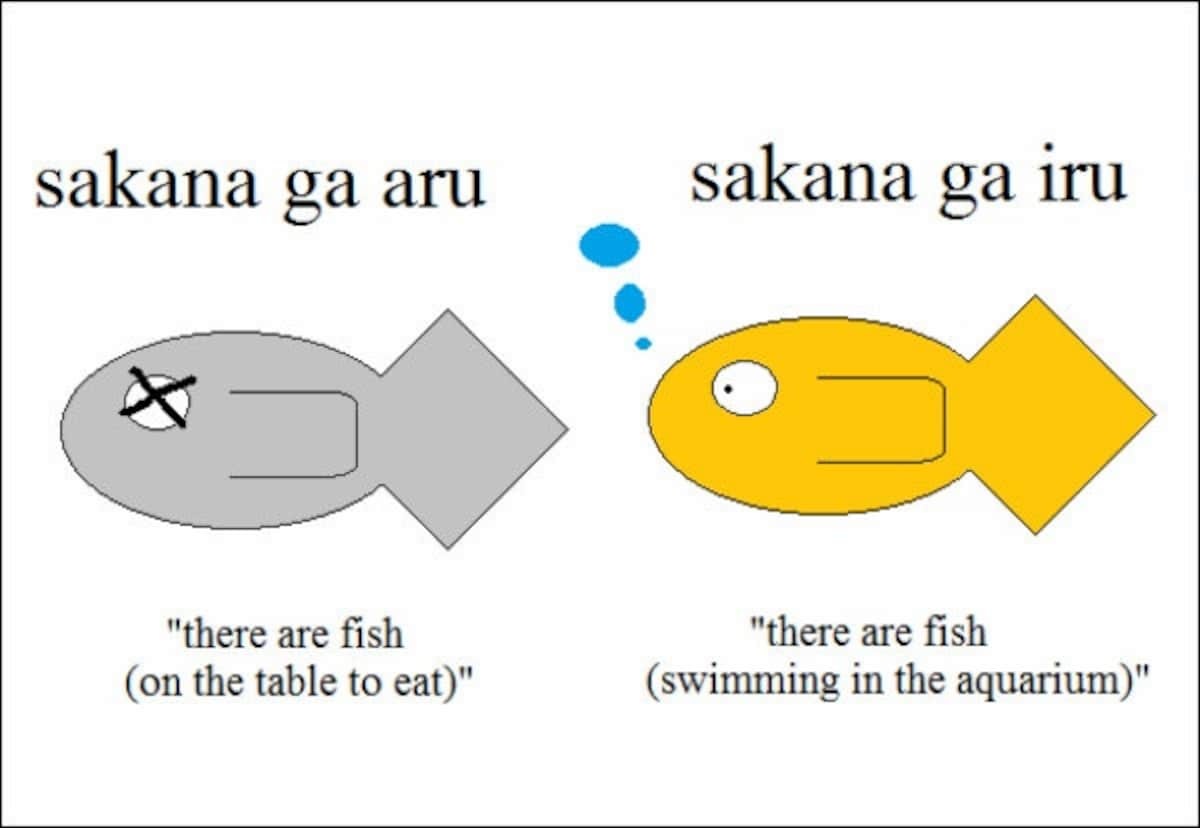

In English, the sentence, “There are fish” could mean either, “There are fish (swimming in the aquarium)” or “There are fish (on the table to eat).” In Japanese, however, there's a distinction between saying “there is/are” something depending on whether it’s alive or not.

For example, if you say "Sakana ga aru," that would mean “There are fish (on the table to eat).” But if you say "Sakana ga iru," that would mean “There are fish (swimming in the aquarium).” The word aru is used for inanimate objects, and iru is used for animate objects.

The most difficult part about differentiating between aru and iru is simply not getting into the habit of using aru all the time. Most of the time you ask someone if they have something, or you’re telling them you have something, that something is non-living. Money, cars, video games, food, and more are all discussed using aru.

Since aru is used so often, it’s easy for the Japanese learner’s brain to assume that it means “there is/are” in all circumstances and get in the habit of using it all the time. But then they might run into trouble when they ask a Japanese person if “there are any children” in their family using aru, and the Japanese listener gives them a confused look.

Just do your best to catch yourself when you make the mistake, say the correct version out loud, and eventually using the right one will become second nature.

5. Differentiating between 'sono' and 'ano'

http://en.rocketnews24.com/2015/12/12/seven-mistakes-foreigners-make-when-speaking-japanese-and-how-to-fix-them/

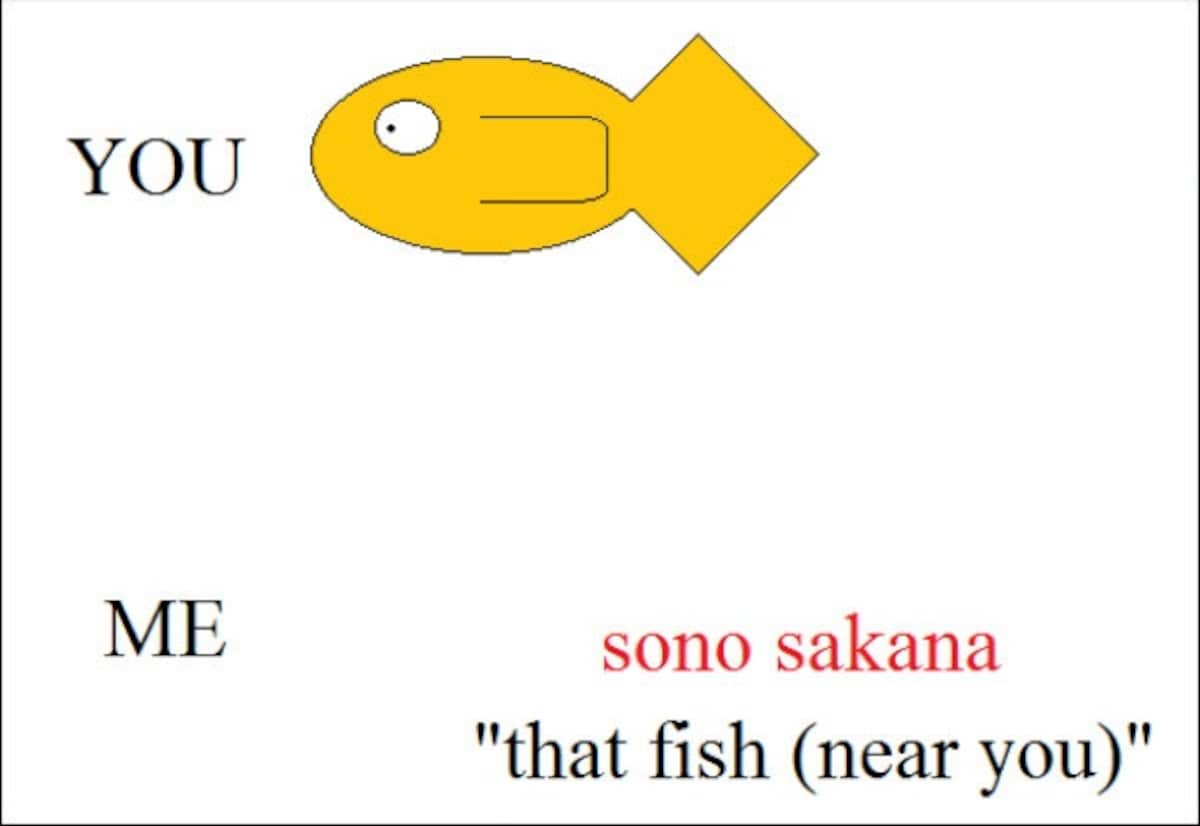

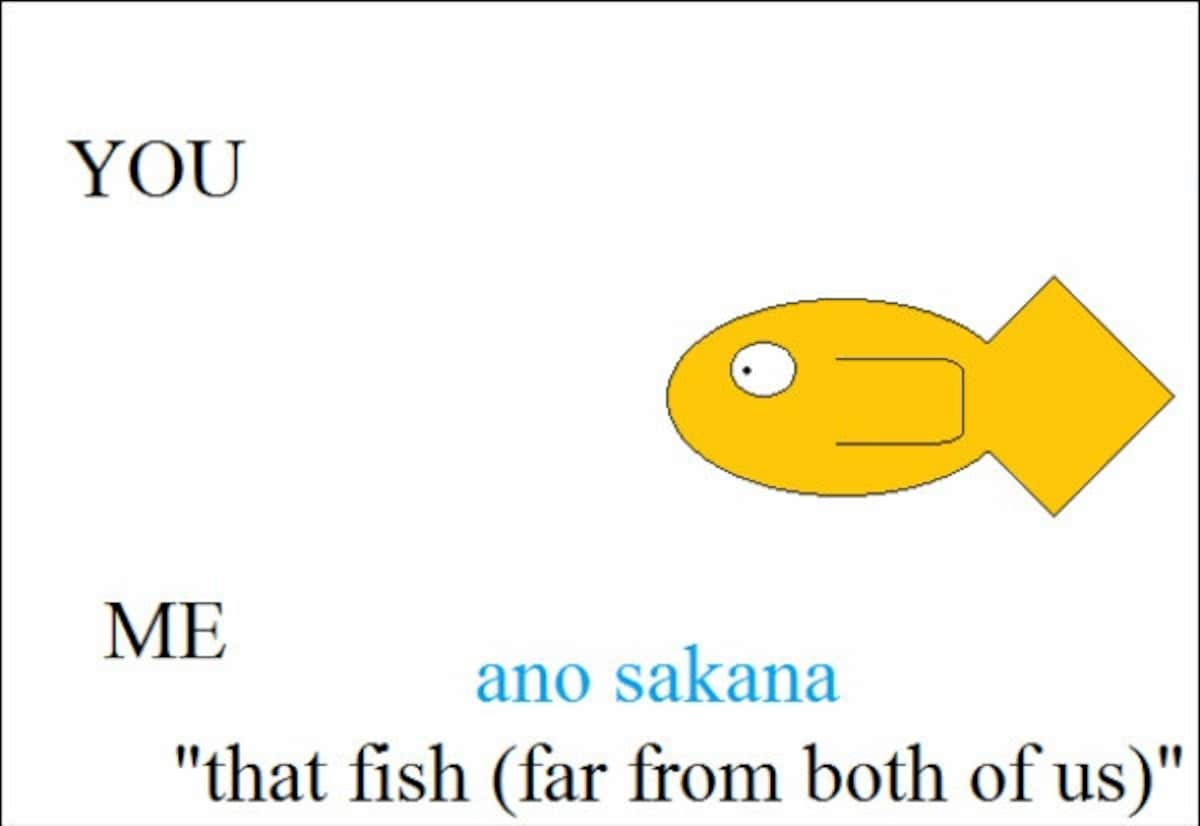

In English, we only have two words used to refer to objects at a distance: “this” and “that.” In Japanese there are three, commonly taught as: “this ___” (kono), “that ___” (sono), and “that ___ over there” (ano).

Because the three levels of distance are often taught this way, it can be easy for students to mess them up, especially sono and ano, which both essentially mean “that ___.” There’s not much difference in English between “that” and “that over there” in the first place.

However, the most common way to differentiate between sono and ano is easy: sono means “that thing near to you, the person I’m talking to,” whereas ano means “that thing far away from both of us.”

http://en.rocketnews24.com/2015/12/12/seven-mistakes-foreigners-make-when-speaking-japanese-and-how-to-fix-them/

Again, probably the hardest part about this one is Japanese learners falling into the habit of just using sono or ano all the time to mean “that ___.” Just like with differentiating between aru and iru, do your best to catch yourself when you make the mistake, and then be sure to say the correct version out loud. Eventually the right one will just come out on its own.

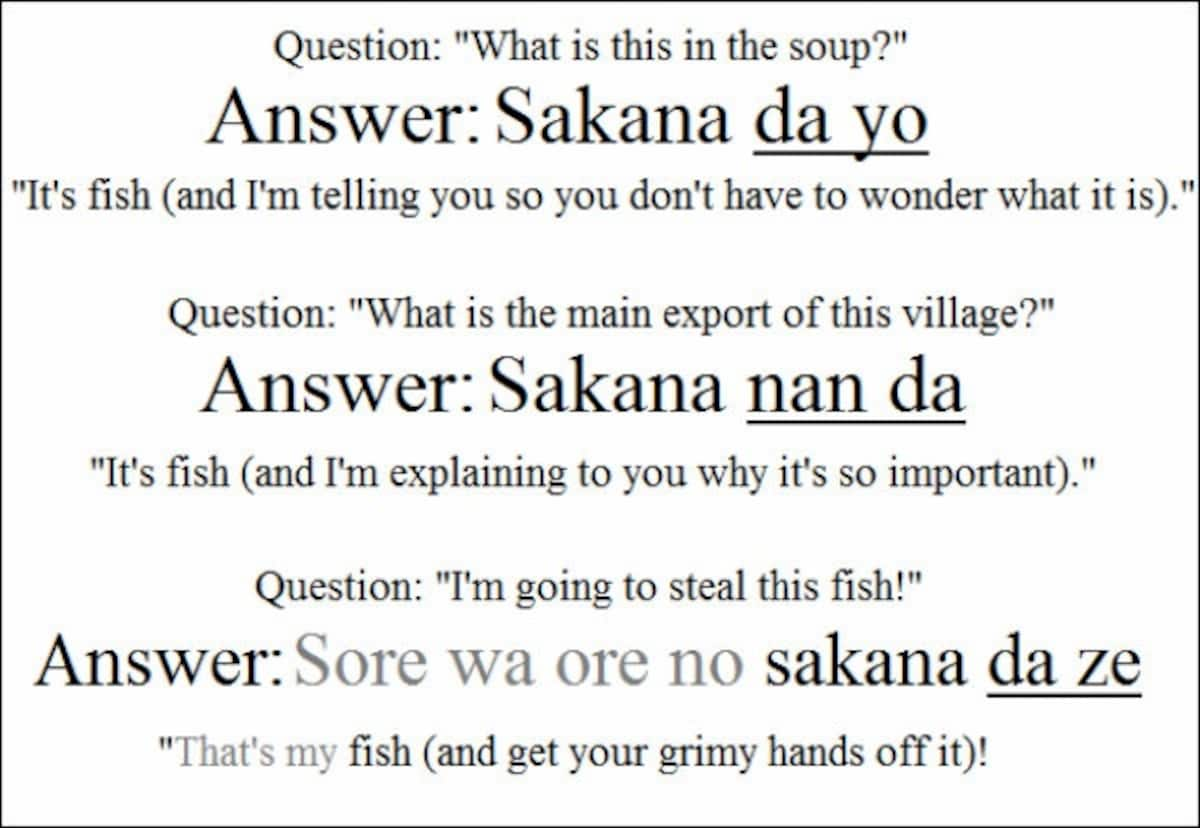

6. The nuances of end-of-sentence particles

http://en.rocketnews24.com/2015/12/12/seven-mistakes-foreigners-make-when-speaking-japanese-and-how-to-fix-them/

Just like particles can come after nouns to explain the noun’s role in a sentence, they can also come after the verb at the end as well, to give a certain “flavor” to the whole sentence. There are the obvious particles like ka that turn a sentence into a question, or ne that ends the sentence with something like “right?” or “you know?” But then there are the not-so-obvious ones. For example, yo, which highlights an assertion; (na)nda, which is used for “explanatory emphasis;” orze which makes the sentence masculine or tough-sounding.

It can get a little confusing, and since there are so many sentence-ending particles, the best thing to do is to just hear them used by native speakers, then do your best to use them in the same context. You’re going to make mistakes, but if you want to achieve that delicious fish-omelet of fluency, then you’re going to have to crack a few eggs.

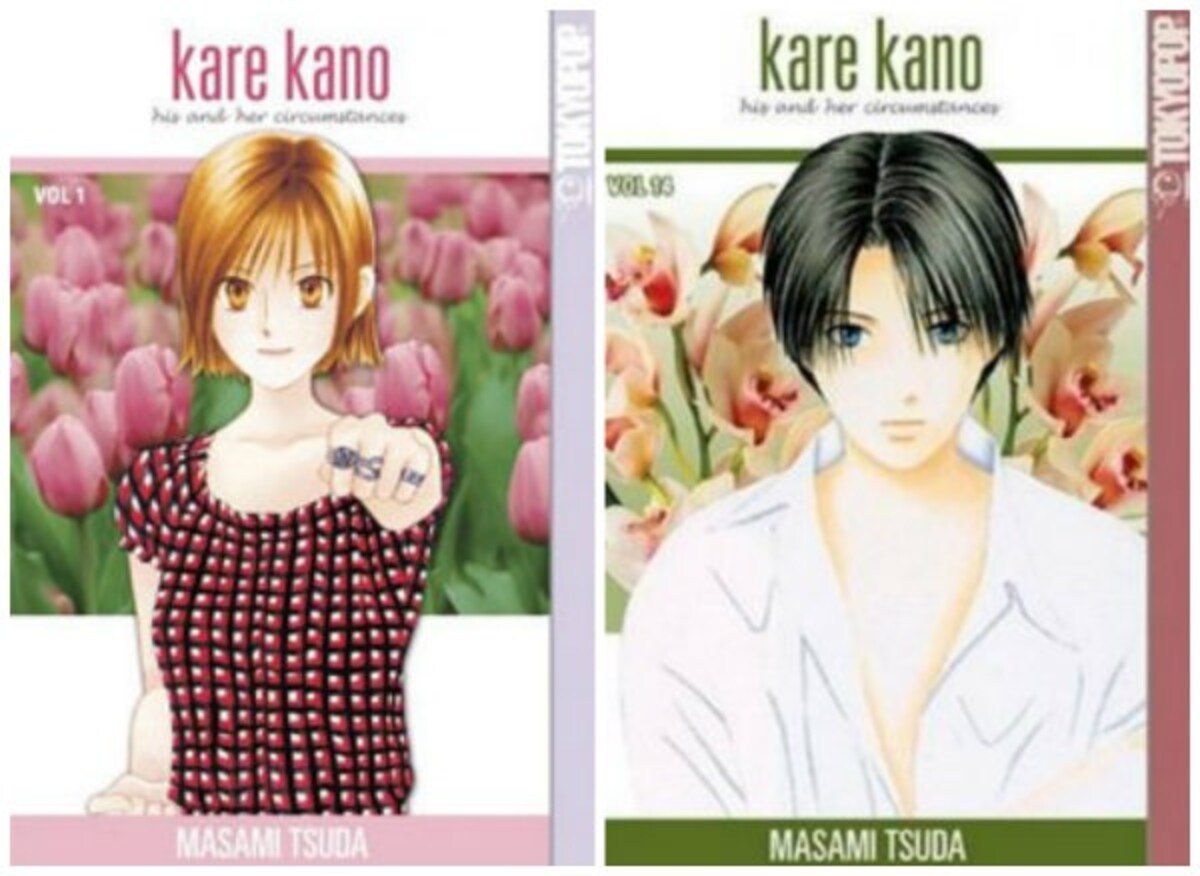

7. Using 'kare' for 'he' and 'kanojo' for 'she'

http://en.rocketnews24.com/2015/12/12/seven-mistakes-foreigners-make-when-speaking-japanese-and-how-to-fix-them/

Japanese loves to drop subjects (and objects, and verbs, and basically anything) from sentences if it’s already obvious from the context. For example, in English we would say: “I saw Bob yesterday. He was eating fish.” But in Japanese, we could say: “Saw Bob yesterday. Eating fish.” The person who saw Bob (I/the speaker) is obvious from the outset, and we already know we’re talking about Bob in the second sentence, so there’s no need for the “he.”

But old habits die hard, so for English speakers especially, it’s tough to stop using pronouns like “I,” “you,” “he” and “she.” And when it comes to “he” and “she” especially, there’s a special reason using the Japanese equivalents could be troublesome. In Japanese the word for “he” is kare and “she” is kanojo. Unfortunately, kare and kanojo also mean “boyfriend” and “girlfriend” respectively. So if a non-native Japanese speaker says something like: “I saw Bob yesterday. He was eating fish,” it may come out sounding like: “I saw Bob yesterday. Boyfriend was eating fish.”

What’s the best way to avoid talking to Japanese people about your boyfriend/girlfriend when you don’t mean to? Just stop using pronouns altogether. Need to talk about someone? Use their name. Need to talk about yourself? Just say what you did and don’t bother with “I.” It may sound awkward at first and it is a bit extreme, but it will help get your brain used to not using pronouns.

So there you have it: the top seven mistakes that foreigners make when speaking Japanese and some tips on how to help fix them. However, the most important tip comes at the end: when learning a language, far and away the most important thing you can do is not worry about making mistakes and just speak. Eventually the correct way to say something will just feel right, and that’s the best feeling in the world!

Related Stories:

RocketNews24’s six top tips for learning Japanese

The top 10 hardest Japanese words to pronounce – which ones trip you up?

Five words that sound completely different across Japanese regional dialects