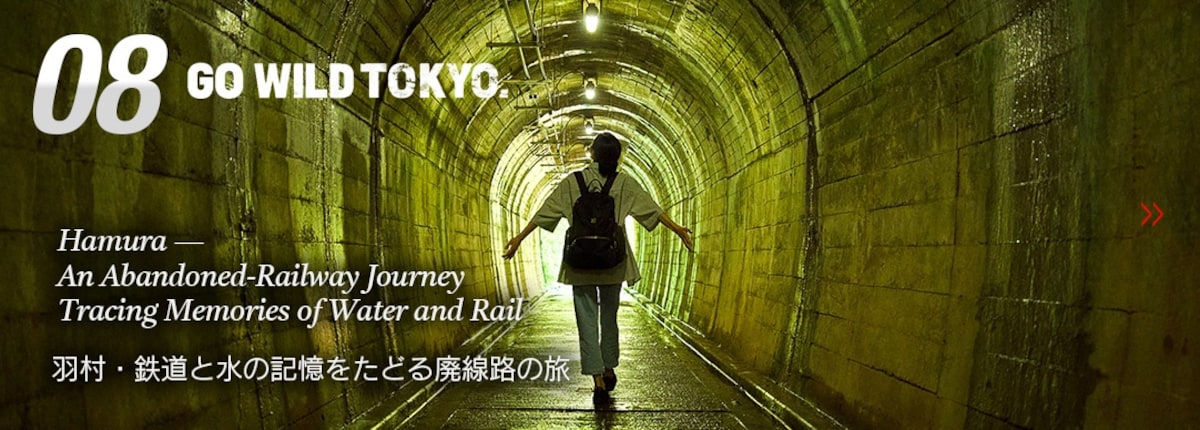

GO WILD TOKYO 8 / Hamura — An Abandoned-Railway Journey Tracing the City’s Memories of Water and Rail

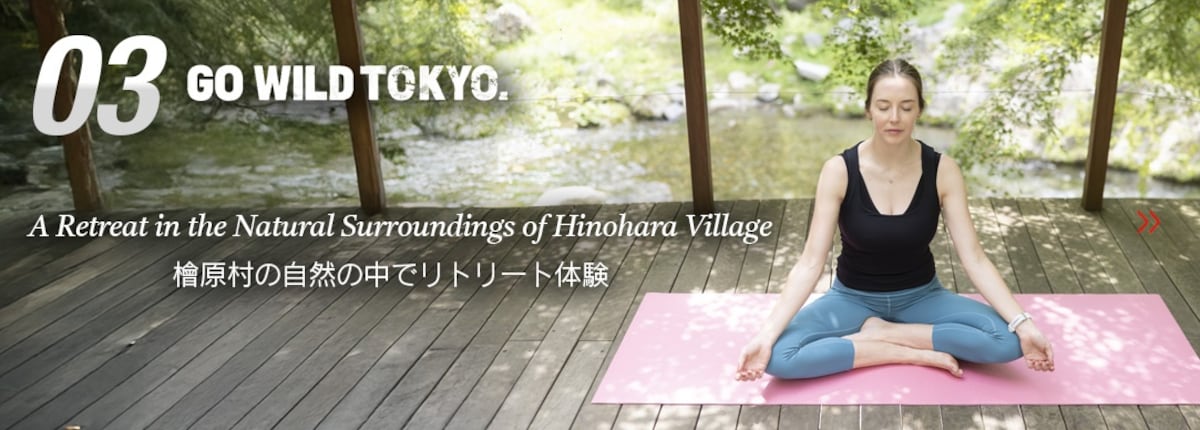

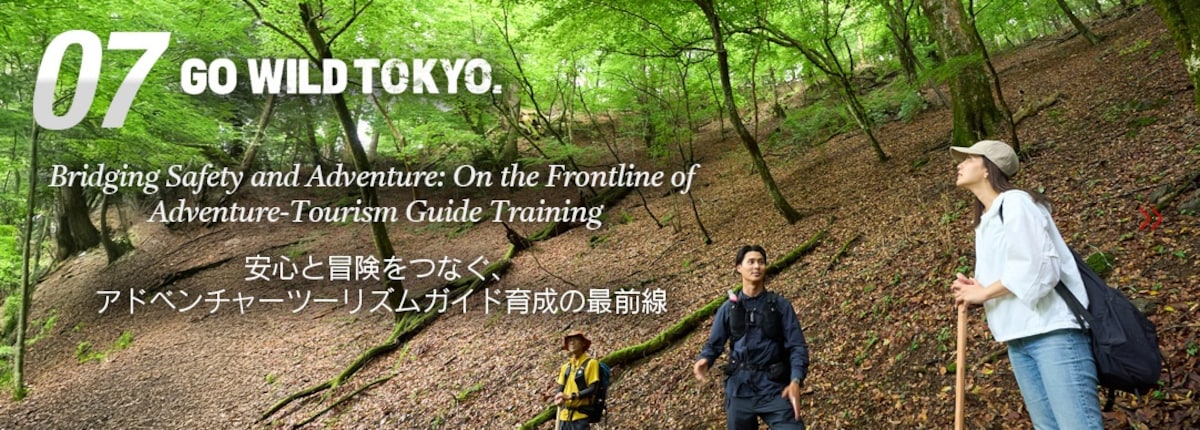

When people think of Tokyo, many picture skyscrapers and buzzing streets—but did you know the metropolis is also home to remarkable nature? Venture a little beyond the city center into the Tama and island areas and you’ll find landscapes that feel worlds away—perfect places to step out of the urban rush and reset. A style of travel increasingly popular with visitors is “adventure tourism,” built on at least two of three elements: nature, activities, and cultural experiences. Why not leave the everyday behind and set out to discover something new? GO WILD TOKYO!

By AAJ Editorial TeamHamura City, along the middle reaches of the Tama River, is a compact municipality where people and water systems have long coexisted—and where diverse wildlife and human life still share the landscape. In the Edo period, excavation of the Tamagawa Josui aqueduct brought water to Edo. From the Meiji through the Showa eras, construction of the Murayama Reservoir and Yamaguchi Reservoir made Hamura the starting point for sending water to Tokyo—and remain as sources that sustain daily life. Through tours that trace the route of the former Hamura–Yamaguchi Light Railway that was used to build those reservoirs, the Hamura City Tourism Association shares the region’s role and history.

Hamura: A City of Aqueducts and Rail

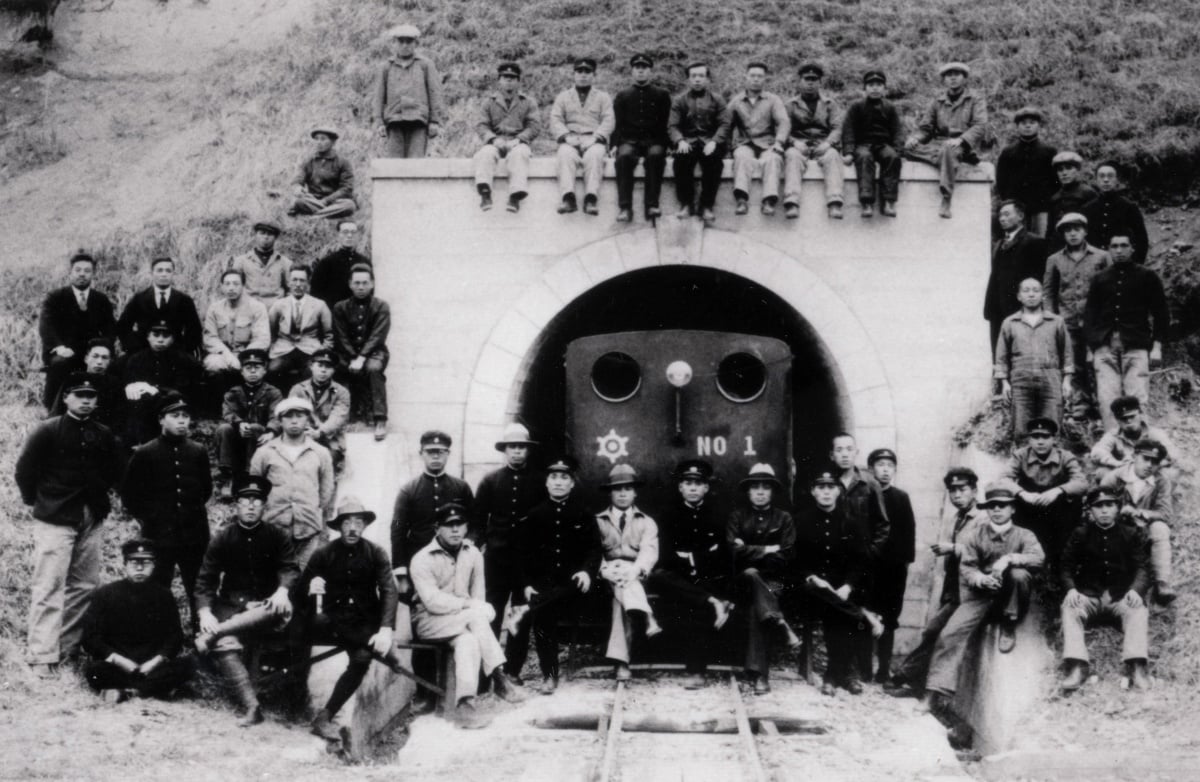

Taisho to Early Shōwa-era photo. A Scene from the train heading to inspect a reservoir. Originally a freight line, it was not often used by passengers. Courtesy of Tokyo Waterworks Historical Museum.

Between Hamura City and Musashimurayama lies a “phantom railway” that never appeared on contemporary maps and remains little known today: the Hamura–Yamaguchi Light Railway.

Around the end of the Meiji era, a stable water supply became a pressing issue as Tokyo’s population surged. The Murayama Reservoir at Lake Tama was built as a countermeasure, and a new conduit was planned to carry water eastward from the Hamura Weir on the Tama River.

To transport construction materials for that project, tracks were laid for a light railway covering about 8 kilometers from Hamura to Yokota in Musashimurayama.

The rails were removed after the Murayama Reservoir was completed. After Tokyo’s population continued to grow, the light railway was restored along the same route to haul materials to build the Yamaguchi Reservoir at Lake Sayama.

When the work finished in 1931, the line was decommissioned, though some rails were left in place. Toward the end of World War II, defensive works were carried out to protect the reservoirs from air raids, and the light railway was temporarily revived to carry needed supplies. After that ended, the rails were completely removed and the railway’s role ended.

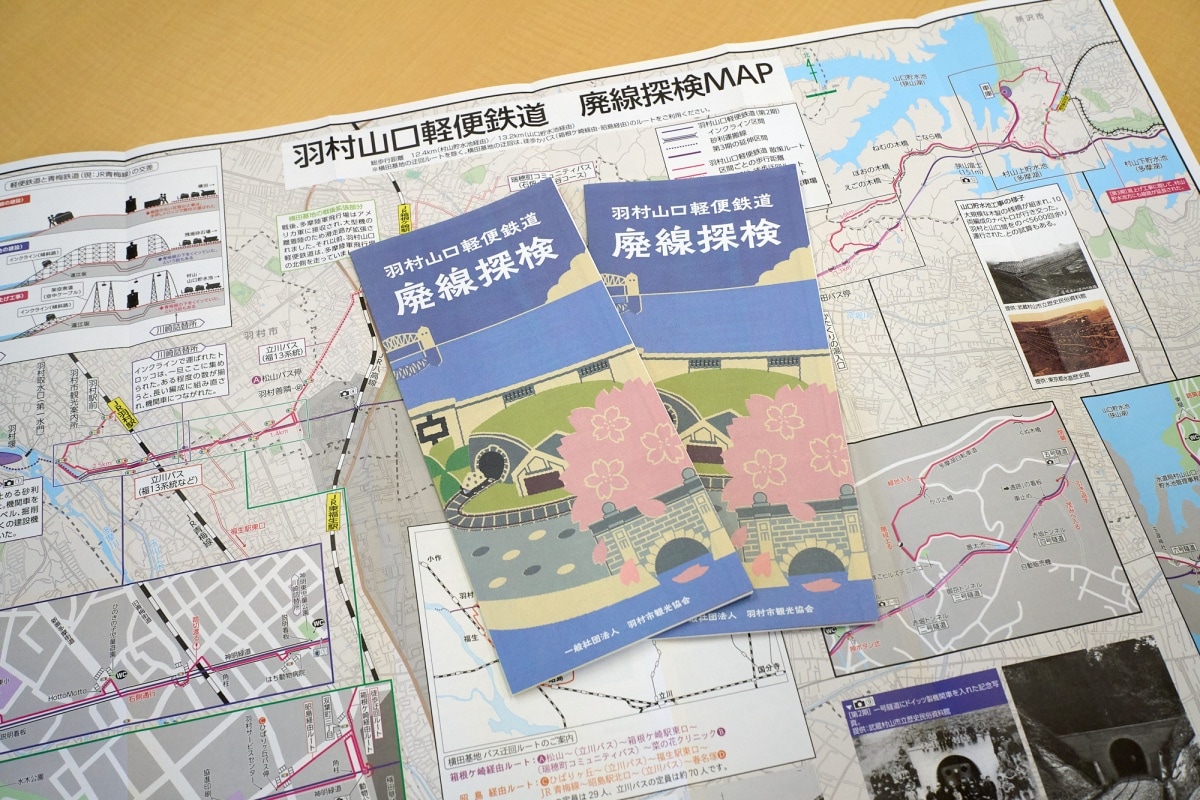

Walking with an “Exploration Map” in hand—the light railway once ran directly above the still-active conduit linking Hamura and Murayama.

Hamura Intake Weir: a portion of the Tama River water taken at Hamura is diverted via the No. 3 gate of the Tamagawa Josui Hamura Intake to three destinations—water treatment plants, reservoirs, etc.—ultimately becoming tap water for Tokyo residents.

A section of the former right-of-way has been turned into today’s Shinmei Greenway; a metal pillar marks the entrance as an abandoned line.

Since 2021, the Hamura City Tourism Association has run the “Hamura–Yamaguchi Light Railway Abandoned-Line Exploration” tour. Starting at the Hamura Tourist Information Center, the walk follows the Tamagawa Josui and traces remnants of the former railway.

Along the way you’ll find leafy promenades, four tunnels, and a stop at Tamanoumi Shrine, before ultimately heading for either the Murayama or Yamaguchi Reservoir.

It’s a quietly profound tour that lets you experience Hamura’s natural surroundings while appreciating the history of the landscape.

Following the Greenway Along the Old Line

Time flows gently on the Shinmei Greenway—perfect for communing with nature and reflecting on history.

Using the tour pamphlet as a guide, we walked the section of abandoned line now maintained as the Shinmei Greenway. Running straight through a residential area, the seemingly endless line of sight hints at the railway that once passed here.

The Hamura–Yamaguchi Light Railway used a 609-mm gauge—much narrower than today’s JR lines. Because of that, the path itself feels compact. In the summer season, vegetation crowds close on both sides. The rustle of leaves and occasional birdsong are soothing, and even under the strong sun a soft breeze keeps your steps light.

Near Yokota Air Base the trace breaks briefly, but it can be picked up again beyond the base—where the tour’s showstoppers appear.

Many visitors are caught by surprise at the four tunnels strung quietly along the green trail. Now part of the Noyamakita Park Bicycle Path, they are open to pedestrians. Each tunnel has a name, keeping memories of the line alive.

The texture of the wooden formwork imprinted on the tunnel lining conveys the weight of history.

A commemorative photo at the west entrance of the First Tunnel (now Yokota Tunnel), likely taken in the early Showa era. Courtesy of Musashimurayama City Museum of History and Folklore. (provided by Mr. Mamoru Akiyama).

“In summer they’re cool, in winter they’re warm, so many people say it feels like stepping into another world,” says Shigeo Tanaka, Secretary-General of the Hamura City Tourism Association, which runs the tours. “If you look closely at the walls, you’ll see wood-grain patterns—that’s the imprint of the timber forms used when the concrete was poured.”

Lit by dim light, the plain, warm surfaces—so different from modern tunnels—are striking. It’s easy to imagine the construction work of the time and the light railway hauling materials through.

Beyond Akasaka Tunnel toward the closed Fifth Tunnel, the path is quintessential Musashino forest—listen for the bush warbler’s call.

Moments That Touch Everyday Life and Culture

In Musashimurayama and the surrounding area, locals have eaten wheat-flour udon since the Edo period.

For lunch we visited the restaurant Nikujiru Udon Aoyagi in Musashimurayama—once linked to Hamura by the light railway—to try the local specialty Murayama Kate udon. Here kate (“provisions”) refers to seasonal local vegetables, boiled and served alongside the noodles. The noodles are robust, slightly brown thick strands made with domestic wheat—firmly chewy in the Musashino udon tradition.

The classic style is to dip the noodles into a hot broth. The stock is made of dried fish flakes, kombu, and dried sardines, and finished with concentrated soy seasoning. The balance between the springy noodles and rich broth is spot on and deeply satisfying—exactly the energy boost you want before the afternoon’s walk.

Inside the museum you’ll even find replicas of historic and modern sluice gates—impressive in their scale.

To deepen your understanding of the light railway and Tokyo’s waterworks—and heighten your enjoyment of the tour—be sure to stop by the Hamura City Local Museum, celebrating its 40th anniversary.

Exhibits include a working model of the Hamura Intake Weir and replicas of sluice gates. If you visit before taking the walk your experience during the walk will be enhanced.

Though Hamura is Tokyo’s least populous city, its role in supplying the metropolis with drinking water is remarkable. Encountering the lives of people who have lived with—and protected—this water offers a renewed sense of the area’s important history.

Outdoor exhibits offer a glimpse of daily life in earlier times.

Don’t miss the beautifully arranged outdoor displays. The first thing you’ll see is a red-roofed gate with a small shelter. Once part of an Edo-period physician’s home, it later stood at the memorial museum of Hamura-born author Kaizan Nakazato before being relocated here.

Farther in is the Former Shimoda Residence, a farmhouse reconstructed from 1847 and designated an Important Tangible Folk Cultural Property. With its thatched roof and period tools, it brings village life of the time within reach.

Hamura’s Appeal—Where Nearby Nature and Industrial Heritage Speak

Shigeo Tanaka, Secretary-General of the Hamura City Tourism Association, has shone a light on the little-known story of the Hamura–Yamaguchi Light Railway—planning the Abandoned-Line Exploration tour and producing pamphlets and maps.

The “Hamura–Yamaguchi Light Railway Abandoned-Line Exploration” tour, designed by Hamura City as a cross-cultural experience, does more than trace a dormant history. It invites you to savor Musashino’s rich nature while learning about the blessings of the Tama River and Tamagawa Josui—and how they connect to Tokyo’s waterworks.

Shigeo Tanaka is Secretary-General of the Hamura City Tourism Association. “Hamura has played a major role in Tokyo’s water supply—through the Tamagawa Josui and through the light railway that supported the Murayama and Yamaguchi reservoirs,” he says “But nearly a century after those reservoirs were built, much of that history has faded from memory. Even many Hamura residents know little about the railway.

He hopes that the more they know, the more people will be able to appreciate the site. “Though the tracks are gone, the conduit beneath still sends water to the Murayama Reservoir,” he says. “I hope people will look again at its value—overlaying old photos and memories on the scenes before them.”

First, stop by the Tourist Information Center near Hamura Station for the course-map pamphlet. They also provide route guidance and rent e-assist bicycles (paid).

Across the Tama River, the Kusabana Hills rise to two or three hundred meters, forming Hamura Kusabana Hills Nature Park. The park is complete with hiking trails. Modest peaks such as Mt. Daichousan (192 m) and Mt. Sengendake (235 m) are perfect for short climbs. In the area, you may encounter plants collected by famed botanist Tomitaro Makino, as well as a diversity of birds and insects.

Hamura also has unique seasonal sights, including the Nagewatashi Weir, which uses the river’s natural flow and is released entirely during high water, and the Yakumo Shrine Mikoshi River-Entry, where portable shrines are carried into the Tama River. Let the abandoned-line tour be your gateway to rediscovering Hamura’s nature and culture.

Information boards along the route explain what each spot looked like in its day.

At the tour’s end point, Yamaguchi Reservoir, the lake opens out beyond an arbor.

Hamura Tourist Information Center

1-13-15 Hanehigashi, Hamura, Tokyo [MAP]

Access: 3 minutes’ walk from JR Ome Line Hamura Station (West Exit).

Tel: 042-555-9667

Hours: 9:00–17:00 (closed days: see official site)

URL: https://hamura-kankou.org/

SNS: X https://x.com/hamurakanko

※This project was carried out with support from the Tokyo Convention & Visitors Bureau (TCVB) Adventure Tourism Promotion Grant.

Text: Ryuji Muratsugi Photos: Tatsushi Yuasa