Five Women Warriors from Japanese History

Samurai, street fighters, and shamanesses--Japan has its share of fighting women over the centuries. Here are five of the country's most celebrated warriors.

By Hiroko YodaTales of the samurai are synonymous with swordsmen around the world, but in fact some of Japan’s most celebrated warriors were women. Technically, women couldn’t become samurai. But samurai was a social class as well as a title, and if you were born or married into a samurai family, you were aristocracy as well.

In times of old, it’s true, only men were officially allowed to venture into battle, but there were rare exceptions. And it was also common for the spouses of samurai to train in the martial arts to help defend their families in times of need. Over the centuries, many women proved their mettle both on and off the battlefield. Read on for profiles of five of the most famous.

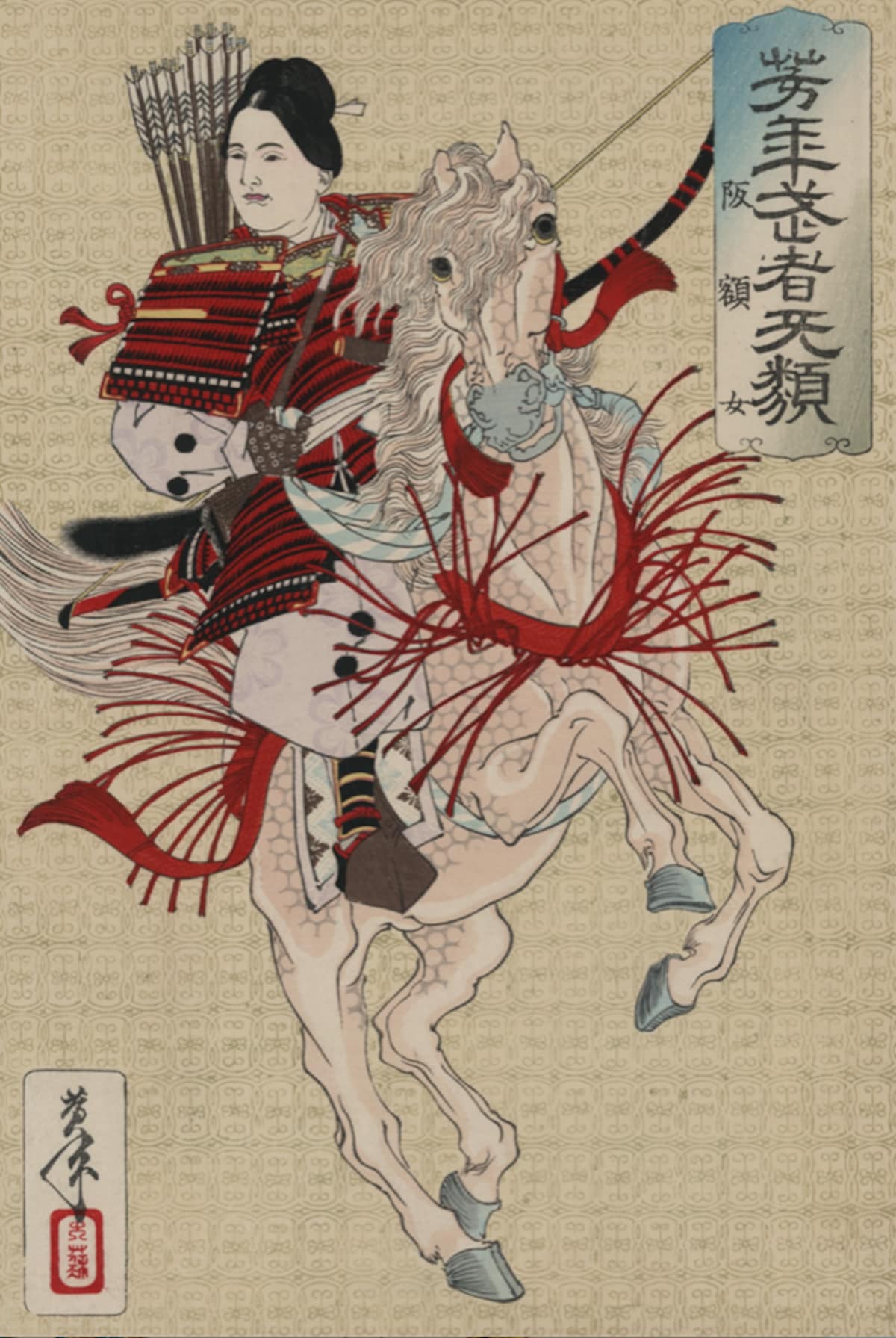

Tomoe Gozen: Genpei Warrior

Tomoe Gozen, painting by Shitomi Kangetsu (Wikipedia Commons)

Nobody is quite sure when this prototypical female warrior of Japanese legend was born or died, but her legend has burned brightly for close to a millennium.

“Tomoe was especially beautiful, with white skin, long hair, and charming features,” gushes the 14th-century war chronicle Tale of Heike. “She was also a remarkably strong archer, and as a swordswoman she was a warrior worth a thousand, ready to confront a demon or a god, mounted or on foot.”

In her most famous exploit during the Genpei War (1180-1185), she rode into battle, wrestled a fully armored samurai from his steed onto her saddle, and beheaded him on the spot. To this day, naginata spears with curved blades are known as “Tomoe-gata” in her honor.

Gozen is actually a title, not a name; it translates into something like “her Ladyship.” But this bit of flair is fairly modern: it was added in the 19th century, when Tomoe became the subject of popular entertainment in the form of Noh and Kabuki plays. There’s an argument to be made that Tomoe is Japan’s first superstar pop-cultural character.

Gracia Hosokawa: Courageous Christian

Born Akechi Tama, she never took up a weapon in combat, but her fiercely independent spirit inspired generations of Japanese rebels. Described as “beautiful in countenance, spiritual, sensitive, discriminative, highly refined, and intelligent,” she was the daughter of Akechi Mitsuhide, who murdered his master the warlord Oda Nobunaga in an attempt to take power for himself. Tama spent the years after her father’s failed coup a virtual prisoner of her own husband Tadaoki Hosokawa, kept in his castle under lock and guard lest she prove a traitor too.

During her confinement, Tama learned of Christianity from a handmaid. She chose to be baptized, taking the name Gracia. She, in turn, baptized her two children. When her husband learned of this, he exploded in rage, and set about making her life a living hell. At one point, he even brought a severed head to the dinner table in an effort to mock her. When this left her unfazed, he screamed, “You are a snake in the guise of a woman!” To which she defiantly replied: “A snake is a suitable wife for a snake.”

When her husband was away in battle and a rival attempted to take her hostage, Gracia chose death rather than let herself be taken prisoner again. After helping her children escape with a Christian comrade, she calmly ordered her servant to execute her. Her conviction, composure, and fearlessness in the face of certain death inspired many – including, centuries later, author James Clavell, who used her as the inspiration for the character Mariko in his bestselling 1975 novel Shogun.

Koman: A Handmaid's Tale of Bravery

Woodblock print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (Wikipedia Commons)

The handmaid to the wife of a mid-ranking warlord, Koman earned fame for defending her family against unimaginable odds. It was she who spirited away his wife and two children after he became embroiled in a dangerous political intrigue. This was no easy matter. In the late sixteenth century, the streets were not safe for unaccompanied aristocratic women, for rivals or rogues might kidnap them for ransom.

Koman put every ounce of her wits, initiative, and daring into the escape. She snuck out and arranged a boat for transport, then dressed her charges as religious pilgrims to shield their identities. First on water, then on foot, she guided them towards the sanctuary of Kyoto’s Kiyomizu Temple. After reaching the city, however, they were accosted by the leader of a streetgang and his henchmen, who saw through their disguises.

So it was that Koman, her mistress, and two babies faced off against a horde of ten thugs. The robbers undoubtedly imagined easy pickings, but Koman and the mother were trained in the sword. They unsheathed hidden daggers and rushed at the men. A pitched battle ensued in the middle of downtown Kyoto. The mother fought like a banshee, taking down four as she shrieked “accompany me to death!” Meanwhile, Koman made quick work of the rest. By the end of it, all ten of the attackers lay dead at the women’s hands.

Unfortunately, her mistress was fatally wounded, as was the little boy. But Koman took the daughter to safety at Kiyomizu Temple, where she was reunited with her father.

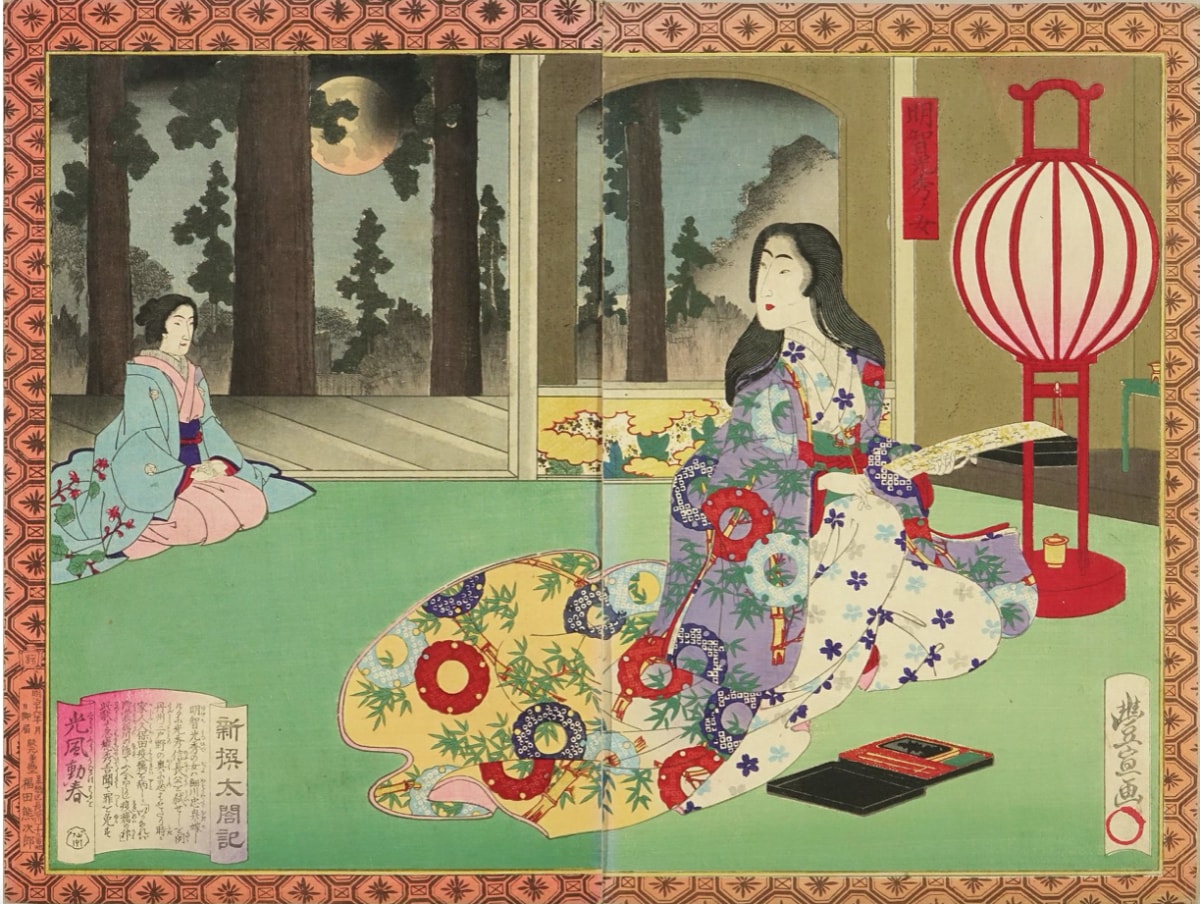

Hangaku Gozen: Death-dealing Archer

The female warrior samurai Hangaku Gozen by Yoshitoshi (Wikipedia Commons)

Described as “fearless as a man and beautiful as a flower,” Hangaku fought in the Kennin Rebellion of 1201. Charged with the defensive operations of Torisaka Castle, she was famed for her strategic thinking and charismatic leadership. Dressed in a man’s clothing and armor, she braved hails of enemy arrows directed at the castle tower, where she stationed herself to better direct the troops inside.

Her bravery inspired, but so did her fighting skills; she was said to be a far better archer than her father and brothers – “shooting a hundred arrows and hitting a hundred times,” according to one contemporary chronicle. It was her marksmanship that kept the attackers at bay for so long; all who fell in her sights saw their steeds killed and shields shattered before she finished them with precisely-aimed shots to breast or head. It was only after taking horrific losses that one member of the attacking side managed to launch an arrow that pierced her thigh. When she fell, so too did the castle.

Taken prisoner, she was presented to the Shogun Yoriie. Normally, rebels would face a death sentence, but the Shogun’s retainer Asari Yoshito was so taken by her that he promptly requested her hand in marriage.

Princess Takiyasha-hime: The Avenging Sorceress

"Mitsukuni Faces the Skeleton-Spectre," woodblock print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (Wikipedia Commons)

Taira no Masakado was a 10th century warlord who launched a hugely popular but ultimately unsuccessful coup d’etat against the Emperor. It ended with his head displayed on a pike on Kyoto’s Kamo River, but tales of his doomed bravery spawned legends that lived on for centuries after his death. One of the most well-known centers on the purported grave of his head in downtown Tokyo, a spot of land considered so haunted that even the American Occupation Forces abandoned plans to move it.

Another famed legend centers on his daughter, the Princess Takiyasha. Though she left little beyond her name in the historical record, centuries after her passing she was resurrected in the flourishing pop-cultural scene of 19th century Edo. Reframed as a sorceress hellbent on avenging her father’s murder, she became the femme fatale of a blockbuster 1836 kabuki play called “Masakado.” In it she uses occult powers to defeat far more powerful samurai. It seems she stole the show, for portrayals of her abound in merchandise such as paintings and woodblock prints.

Chief among them is Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s “Mitsukuni Faces the Skeleton-Spectre,” which features Takiyasha-hime in the ruins of Masakado’s palace, conjuring up a gigantic skeleton to attack a pair of samurai who have come for her. The dynamic scene is one of the singular most recognizable images in the Japanese artistic pantheon.