Time Travel with Japan's "Warlord" Clocks

Tokyo is a city in constant flux, with old buildings vanishing in the wink of an eye. In the historic Yanaka district, though, time seems to stand still. And at Yanaka’s Daimyo Clock Museum it feels frozen solid. It’s the perfect place to admire the fascinating Japanese timepieces from the Edo period (1603–1867) known as daimyo clocks.

By Tim Hornyak

The museum is tucked away behind a temple-lined slope known as Miura-zaka. Past an old wooden gate, a ramshackle kura warehouse and a cramped garden dominated by a Buddha statue, there’s a small concrete building housing about fifty Japanese clocks of various types. This was the collection of Guro Kamiguchi (1892–1970), a local artist and clothing merchant whose family opened the museum in 1974. Most of the clocks here are topped with elegant metal domes and mounted on pyramidal wooden towers. Standing between 1 and 2 meters tall, they look like miniature lighthouses. It’s no wonder they’re also called lantern clocks in English and yaguradokei (turret clocks) in Japanese.

The usual term, however, is daimyo-dokei because they were made exclusively for Japan’s daimyo warlords. Wadokei (“Japanese clocks”) is another common name; both date from the 1930s. Daimyo clocks refer to timepieces made in Japan from the 17th to the 19th centuries. Prior to this, Japanese had little use for accurate timekeeping since temples would mark the time for prayers with bells and drums. In 1551, the Spanish missionary Francis Xavier presented a European clock to the daimyo Ouchi Yoshitaka of Suo Province in today’s Yamaguchi Prefecture, and Japanese craftsmen began adapting basic European designs to local needs and tastes. They continued this as Japan entered the sakoku period of isolation in the Edo period, when it was deprived of European clockmaking innovations like the pendulum and balance spring.

"The Rat is at the six o’clock position, the Hare at nine, the Horse at 12 and the Cock at three."

Yaguradokei or turret clocks have ornate faces featuring an outer ring of kanji characters for the 12 animals of the Chinese zodiac and an inner ring of kanji representing numbers 4 to 9.

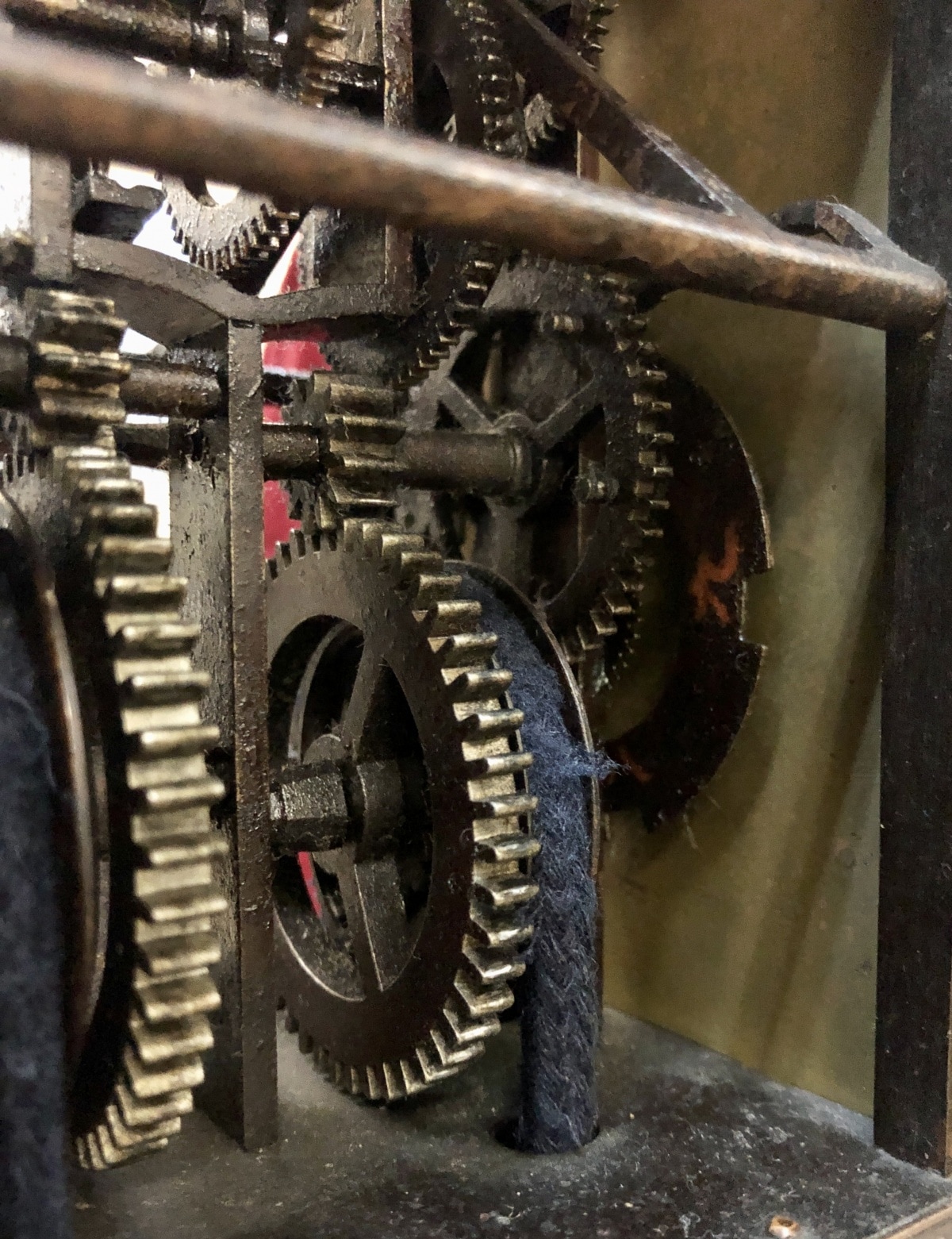

Driven by weights on long chains, the lantern-type daimyo clocks at the museum combine early European clockmaking ingenuity with Edo aesthetics as well as Japan’s traditional way of measuring time. Under this seasonal, nonstandard time system, the length of an “hour” or toki changed both from day to night and season to season. On the summer solstice, for instance, a daytime toki would last about 2 hours and 38 minutes while a nighttime toki would last 1 hour and 21 minutes. On the winter solstice, they would be 1 hour and 49 minutes and 2 hours and 10 minutes, respectively.

To accurately measure nonstandard hours, Japanese craftsmen created a double escapement mechanism of foliots with adjustable weights. Meanwhile, the faces of daimyo clocks also incorporate variable hours. Both day and night were divided into six toki, each named after an animal of the Chinese zodiac and beginning around midnight with the Hour of the Rat, then the Ox, Tiger, Hare, Dragon, etc. On some clocks, the Chinese characters for these animals are inscribed on the clock dials with the top half of the circle representing daytime and the bottom half nighttime. The Rat is at the six o’clock position, the Hare at nine, the Horse at 12 and the Cock at three. To make things more confusing, the dials also bear kanji representing numerals that run, in descending order, from 9 (Rat) to 4 (Snake) and then repeat, from 9 (Horse) to 4 (Boar). It’s not clear why 9 is the starting numeral and why they descend before repeating. Another feature of daimyo clock faces is that the earlier examples featured a moving hand, but this was later replaced by a rotating dial and a stationary indicator.

"Shakudokei, or ruler clocks, had no face whatsoever but used a kind of measuring stick to tell the time: a pointer attached to a geared weight descending along a scale would indicate the hour."

Japanese clockmakers made some timepieces, modeled on European pocket watches, that hung from kimono obi.

Aside from lantern clocks, the museum features a number of other types of wadokei. Before the advent of lantern clocks, incense clocks were used in Buddhist temples to mark time by the burning of incense; one on display at the museum has a mazelike path for the slowly burning incense. Compared to the somewhat clunky yaguradokei, makuradokei (mantel clocks) were compact timepieces with brass mechanisms and spring drives, often displayed in tokonoma alcoves as tokens of wealth. Shakudokei (ruler clocks) had no face whatsoever but used a kind of measuring stick to tell the time: a pointer attached to a geared weight descending along a scale would indicate the hour. They were usually affixed to pillars in daimyo residences and thus nicknamed pillar clocks. Finally, Japanese clockmakers created compact, beautifully wrought timepieces modeled on European pocket watches. Portable inrodokei or seal-case clocks were incorporated into inro, lacquered cases formerly used to carry medicine or other small objects, and hung from kimono obi. Some even had miniature sundials and compasses in their lids.

Japanese craftsmen continued to produce remarkable timepieces, culminating in Tanaka Hisashige’s 1851 Mannenjimeisho, aka Mannendokei or Myriad Year Clock, an engineering masterwork that had six multifunctional clock faces as well as a miniature sun and moon orbiting over a small map of Japan, indicating the positions of the heavenly bodies in the sky; the clock is on display at the National Museum of Nature and Science in Tokyo.

"Today, the terms for morning and afternoon—gozen and gogo—come from the ancient time system, meaning before and after the Hour of the Horse (noon)"

Visitors to the museum can get a close-up view of the gears of a working turret clock and hear its shrill chime.

Only two decades later, the nonstandard time system was thrown out when Japan adopted universal standard time. But Japanese still refer to it every day. The terms for morning and afternoon—gozen and gogo—mean before and after the Hour of the Horse (noon), respectively, and are still used in expressions such as gozen kuji, or 9 am. Like the Daimyo Clock Museum, it’s one way to remember times long past.

The Daimyo Clock Museum

Address: Yanaka 2-1-27, Taito-ku, Tokyo

Hours: open 10 am to 4 pm Monday to Saturday. Closed Sundays and from July 1st to September 30th as well as December 25th to January 14th.

Entry: 300 yen adults, 200 yen university and high school students, 100 yen junior high and elementary school students.

Note that exhibits have explanatory texts in Japanese only but a 100 yen English booklet is available detailing the history of the museum and daimyo clocks.